There is not only one Amazonian culture, but as many as peoples in the rainforest (see anthropological definition of culture ). However, we will refer here to the common traits of the groups of individuals that inhabit the immense Amazon river basin.

Indigenous People Cosmovision

In general terms, we can refer to a common worldview or cosmovision typical to all the Amazonian cultures.

Almost all Amazonian groups have a particular way of relating to nature, with their group and with other people outside their group.

This form of interaction has been built up gradually, sometimes since the very remote past.

That way of thinking about the world, and inserting oneself into it, forms a cosmovision.

The indigenous is formed from childhood within the framework of a worldview that informs him about his relationship with the telluric and uranic gods.

This worldview establishes a hierarchical order of the cosmos, a structure of community life, in which myths (symbols in words) and rites (symbols in actions) are staged, which explains the origin of the world and helps individuals live meaningful lives.

This cosmogonic conception guides their behavior and their perceptions throughout his life as long as they remain in the group (1) .

Amazonian culture vs western culture

For an Amazonian indigenous person, with his or her cultural peculiarities, there is no clear separation between individual and society, culture and nature.

In practice, an Amazonian indigenous person has little or no possibility or autonomy to have an individual behavior different than the group behavior, and the degree of individualism is very weak or almost non-existent, contrary to a society of Western capitalist culture, in which that individualism is a distinctive trait (2).

The person, in an Amazonian society, builds an area full of meanings, in which nature is incorporated into the worldview, attributing meaning to the ethos and the community (3) .

Ethos, understood in the manner of Bourdieu (4) , as a set of rules, strategies or ideological constructs, beliefs, predispositions and habitual practices that shape ideology.

In this case, the person internalizes the landscape and turns it into a leading element in their daily life (5) .

As the Amazon Development and Environment Commission says:

The most important lesson of the indigenous peoples is their insertion in the ecosystems and their close interrelation with them (6) .

For them, “their cosmovision is their portrait, their conception of nature, of the person, of society”, as Geertz points out (7) .

The flow of daily existence translates the rhythms of nature, and things are ordered according to the cycles of nature, day and night, sun and energy.

Myths and legends (cosmogony)

The cosmogony of the peoples of the Amazon is almost as abundant as its flora and fauna . As in other cultures, the myth sometimes seems a way to restrict certain behaviors that are inappropriate, dangerous or that contravene the environmental balance that ensures life. (Learn more about it: Amazonian Food Taboos)

December 15, 2024

The Shaman War

August 16, 2022

Siquihua and lightning

June 8, 2022

Destruction myths: the Universal Deluge in the Amazon Rainforest

October 8, 2020

The legend of the charapa turtle’s owner

October 2, 2020

Acai, the tragic legend of the palm tree that saved an Amazonian tribe

September 30, 2020

4 Creation Myths from Egypt, Greece and America

The curupira

The Curupira, for example, protects those who hunt to feed on the animal and punishes those who hunt for pleasure, to sell the meat to third parties or to accumulate profits.

The Boto Colorado

Thus, the legend of “El Boto Colorado”, is a pink dolphin that transforms into a human to seduce women, this myth helps girls to be careful of strangers.

Yacuruna

A similar myth but with another connotation is that of Yacuruna or “river man” whose importance is fundamental in the low jungle.

Yacumama

The Yacumama or Chullachaqui represents the female deity who cares for the jungle and appears in the form of a boa, anaconda or mapanare snake.

The spirits or “owners” of the jungle.

The indigenous populations share their life, and their values, with spiritual beings who live in the jungle.

The plant and animal world is anthropomorphized (seen as human).

In this context, the reproduction of living conditions, that is, activities related to hunting, fishing, gathering, caring for the farm and the family garden, are mediated by agreements between human beings and “chiefs” or “owners” (spirits) of areas, territories or animals.

In this worldview, each plant, animal or environment has a “chief” or “owner” who lives in the place and preserves it, and from whom permission must be sought to intervene.

This concept of “owner” is shared in a general way by the native Amazonian communities.

For them, this concept of owner is ambivalent, that threatens and protects, mediating between human beings and nature.

The owner transmits the rules of use of the resource, establishing the order and character of the relations between men and nature.

A hunter must not kill an animal without the permission of the “owner”, nor hunt more than what is necessary (8) .

Source: No machine-readable author provided. Amber~commonswiki assumed (based on copyright claims). [CC BY-SA]

Environmental exploitation in harmony with the ecosystem.

In that cosmovision there is no place for the abuse of a natural resource, nor is destructive pressure exerted on the water, the forest, the soil.

Only part of what exists is used.

There is no notable economic surplus, nor a purpose of accumulation of wealth among them, since the Amazonian inhabitants confer to plants and animals the attributes of social life, considering them as subjects rather than objects (9) .

Indigenous Peoples and their languages

The Amazonian indigenous peoples are many and very diverse. Some groups cross borders such as the Yanomami who live between the Venezuelan and Brazilian Amazons or the Achuar who share the border between Ecuador and Peru.

So before differentiating between indigenous ethnic groups of one country or another, it is important to know their families or linguistic trunks.

The Pano language family, for example, is made up of about 30 languages spoken in the Peruvian, Brazilian and Bolivian Amazon Rainforest.

These are the main linguistic families or trunks that exist in the Amazon basin today: Tupí, Ye or Gé, Quechua, Carib, Arawak, Pano-Tacana and Tucana, Jíbaro or Achuar.

Economy

The economy of the Amazon region is conditioned not only by the geographical context, relief, climate, flora and fauna as sources of raw materials, but especially by the rain and the river.

The main modes of economic production or modes of subsistence commonly used among the indigenous people of the Amazon are:

October 19, 2019

Fishing

October 11, 2019

Farming

October 11, 2019

Fish farming

October 11, 2019

Hunting

October 6, 2019

Foragers

October 5, 2019

Tourism

Amazon Rainforest Women

The first impression that the Western world had of them was that they were warriors, but the Amazonian women plays above all the roles of mothers, cooks, farmers, healers, within the framework of customs, beliefs, taboos and ancestral wisdom. They are signed by the family and social group to which they belong.

Typical dishes (gastronomy)

Females are the anonymous signatories of the extensive Amazonian food (roasts, soups, broths, porridges, breads, desserts, drinks ); They are also mothers, artists, creators of fascinating fabrics and drawings (Kene Art), co-creators of dances, of Amazonian music, and they are not limited to that, they also intervene, with their restrictions, in hunting, fishing and gathering.

June 10, 2020

Amazon Rainforest Food and Cuisine from Venezuela

June 8, 2020

Amazonian Cuisine from the Bolivian Low-lands

June 6, 2020

Amazonian Food from Ecuador

June 2, 2020

Amazonian gastronomy of Colombia

June 1, 2020

Amazonian Food: Traditional dishes from the Brazilian Jungle cuisine

May 30, 2020

Amazonian gastronomy of Peru

Amazon rainforest tribes clothing

As we have seen, the Amazon region is home to many cultures and ways of life.

Although the most of the natives have adopted a western dressing style. there are still those who walk around almost naked inside the jungle or wearing their own traditional clothing.

Perhaps the latter are the majority, since more than

From the 30 million inhabitants who live in the Amazon basin, of which less than a

Only one million people or less keep practicing their ancestral customs, out of 30 million inhabitants of the Amazon basin.

The clothing or attire that is used daily is different from the one used in the festivities or the one used when tourists come to visit.

In any case, beyond the classic loincloth or guayuco, there are many types of skirts, often made with vegetable fibers or tree bark. Ornaments are also abundant, such as feathers, animal skin bracelets, necklaces made with animal bones, and paintings with natural pigments such as achiote or onoto (Bixa orellana).

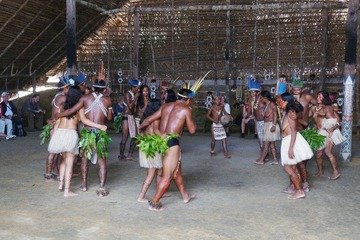

Typical dances

As you can imagine, the tribal dances of the Amazon are many and not all of them have a specific name to identify them, many are supposed to have disappeared and others survived the conquest and still survive today, among them we can mention the following:

From Ecuador we find: the Yuni dance ( typical of the Achuar), Tushuy taqui sacha manda (which means music and dance of the jungle and is typical of the indigenous groups of Pastaza, Orellana and Napo) or the dance of the Wuaodani .

The bambuco is practiced in Colombia and Venezuela, others more typical of the Colombian Amazon Rainforest region are: the Danza de los Novios, the Danza de los Sanjuanes, the Zuyuko dance and the Bèstknatè that celebrates the meeting between two indigenous tribes.

Amazon Rainforest Music

The music is directly related to the dance. In the Amazon region, each musical rhythm or style also has its dance.

Also noteworthy are the Amazonian musical instruments: percussion (indigenous drums such as the manguaré or high drums, bells, rattles or maracas) and wind (flutes, reed and ceremonial trumpets, ocarinas or snail trumpets)

December 9, 2021

Kichwa music from the Amazon-Ecuador

Documentaries

The Amazon region is constantly the subject of video and film records that document the life of its wild animals, its habitat, and its indigenous cultures.

These celluloid or digital records often serve to raise awareness among the population about the importance of valuing, respecting and protecting the jungle of the illegal commercial logging activity , of the fires, pollution from mining extraction, illicit crops and the indiscriminate hunting among other factors that endanger the subsistence of many animal and plant species.

Clarification on the term “culture”

The social sciences consider culture as a totality or unit with a high degree of complexity that encompasses cultural symbols, ideas, norms, customs, values, which function as a mechanism of action and social control that governs the behavior of the members of a group or society, through a learning process known as enculturation.

In a specific society, its members internalize a system of meanings and symbols that they receive from their predecessors as a legacy, through tradition, to imagine the world and place themselves in it.

Culture and anthropology.

According with the North American anthropologist Clifford Geertz, culture is the network or plot of meanings with which we give meaning to the phenomena or events of everyday life. And it acts as a series of control mechanisms that govern the behavior of the members of a group.

In such a way that culture is for a particular human group as its cultural fingerprint, to the point that there are no two human groups with the same culture.

Some consider that this sense of cultural identity that characterizes a group acts as a compass to guide its members in mental maps that make up their lifestyles.

Sources

1 . Zolla, C., Zolla, E. 2004. The indigenous peoples of Mexico. Mexico: UNAM, pp.80-81.

2 . Kottak, C. P. 2011. cultural anthropology. Mexico: McGraw Hill, p. 128.

3 . Gómez-Muñoz, M. 2003. Indigenous knowledge and the environment: experiences in community learning. Leff, E. (Coord.).Environmental Complexity. Mexico: Siglo XXI Editores-UNAM-PNUMA, pp. 255-259.

4 . Bourdieu, P. 1993. Outline of the Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 85.

5 . Cartay, R. 2016. The Peruvian Amazon Table. Ingredients, corpus and symbols. Lima: San Martin de Porres University, pp. 109-110.

6. Amazon Commission for Development and Environment. 1994. Amazon without myths. Bogotá: The Black Sheep, p. 97.

7. Geertz, C. 1991. The interpretation of cultures. Mexico: GEDISA.

8. Macera, P.; Casanto, E. 2011. The Ashaninca magical kitchen. Lima: San Martin de Porres University, p. 77; Chaumeil, JP 1994. The Yagua. Santos, F.; Barclay, F. (Eds.). Ethnographic guide to the Upper Amazon. Quito: IFEA/ FLACSO Ecuador. Vol II, p. 230; Seitz-Lozada, G.M. 2007 . Generational rupture in the Awayún Suhshug, Nayumpin and Wawas native communities during the last decades . SEPIA. Gender and natural resource management. 125-150. Lima: SEPIA, p.127.

9. Descola, P. 2005. The spears of twilight. Jivaro stories from the Upper Amazon. Buenos Aires: Economic Culture Fund, p. 391.

Dr. Rafael Cartay is a Venezuelan economist, historian, and writer best known for his extensive work in gastronomy, and has received the National Nutrition Award, Gourmand World Cookbook Award, Best Kitchen Dictionary, and The Great Gold Fork. He began his research on the Amazon in 2014 and lived in Iquitos during 2015, where he wrote The Peruvian Amazon Table (2016), the Dictionary of Food and Cuisine of the Amazon Basin (2020), and the online portal delAmazonas.com, of which he is co-founder and main writer. Books by Rafael Cartay can be found on Amazon.com

This post is also available in:

![]() Español (Spanish)

Español (Spanish)