After the conquistadors, colonizers and missionaries, European naturalists arrived in the Amazon basin, especially the English, French, Germans and Americans.

Dr. Rafael Cartay is a Venezuelan economist, historian, and writer best known for his extensive work in gastronomy, and has received the National Nutrition Award, Gourmand World Cookbook Award, Best Kitchen Dictionary, and The Great Gold Fork. He began his research on the Amazon in 2014 and lived in Iquitos during 2015, where he wrote The Peruvian Amazon Table (2016), the Dictionary of Food and Cuisine of the Amazon Basin (2020), and the online portal delAmazonas.com, of which he is co-founder and main writer. Books by Rafael Cartay can be found on Amazon.com

Main protagonists of the first scientific expeditions to Amazonia

Scientists already acclaimed in their countries of origin, such as Charles De la Condamine, Alexander von Humboldt or Alfred Russel Wallace, came.

And others, many others, in waves, who wanted to consecrate or enrich their private collections or by governmental mandates. Like Alexandre R. Ferreira, William Henry Edwards, H.W. Bates, Lowe, Johann von Spix, Karl F. von Martins, F. D. Roulin, J.E. Pohl, Robert Avé- Lallemant, Maximilian Zu Wed, G. H. Langsdorf, R. Schomburgk, Count Castelanau-Laporte, Charles Waterton, Johann M. Rugendas, Francisco Michelena y Rojas, Prince Alexander Maximilian, Richard Spruce, J. Nattener, Paul Marcoy, Leopold Adametz, Eduard Poepping, Charles Weiner, Heinrich Wilhem Schott, A. Taunay, Adalbert von Preven, Ferdinand Bellerman, Theodor Koch-Grunberg, Hamilton Rice.

Each of them overcame countless dangers and hardships to contribute a new species record to science or leave the legacy of a travel book.

The contribution of Cristóvao de Lisboa, considered the first naturalist of the Amazon region due to his illustrated inventory História dos Animais e Árvores do Maranhao, written between 1624 and 1629, is an antecedent of all of them.

Then came the great expeditions that responded to the desires of European monarchs to learn more about natural resources in order to exploit them for the benefit of their imperial power.

Royal Botanical Expeditions

This chapter includes the Royal Botanical Expeditions, such as the one that went to New Spain, headed by José Mariano Mociño and Martín Sessé y Lacostabetween 1787 and 1803; the Royal Botanical Expedition of the New Kingdom of Granada, between 1782 and 1808, headed by the Spanish José Celestino Mutisin which the later hero and martyr participated Francisco José de Caldas for the independence of Colombia; the Botanical Expedition to the Viceroyalty of Peru, between 1777 and 1788, directed by Hipólito Ruiz López and José Pavón.

Apart from the Española, there was the expedition to Brazil led by the naturalist Alesandre Rodrígues Ferreira, between 1783 and 1792, known as Expedicao Philosophica do Para, Rio Negro, Mato Grosso e Cuyabá.

English expeditions

Other English expeditions, such as the famous expedition led by the botanist Joseph Bank, the physician Daniel Solander and the explorer and cartographer James Cook, who captained the H.R. Endeavour, which traveled halfway around the world and made a stay in Brazil.

French geodesic mission to Ecuador

A famous expedition was the French Geodesic Mission to the Equator, in 1736, to measure one degree of the Earth’s meridian at the Equator and verify the shape of the Earth.

Source: Available in the BEIC digital library and uploaded in partnership with BEIC Foundation.

Members of the French Academy of Sciences: Louis Godin, Charles-Marie de la Condamine and Pierre Bouguer. La Condamine then went on to the Amazon to explore it on his own.

Chorographic Mission to the Caquetá territory

Another important expedition, now of regional importance, that touched part of the Amazon was the Corographic Mission through the territory of Caquetá and part of Colombia.

This was directed by the geographer and cartographer Agustín Codazzi, from 1850 until his death in 1859, who traveled the upper Caquetá and the Putumayo River.

Illustration reaches the Amazon

The great interest that the Amazon awakened among European scientists from the eighteenth century was directly related to the development of what was called the century of the Enlightenment, which stimulated freedom of thought, individual reason, the development of science, economic changes with the industrial revolution and political changes with the French revolution.

Commercial capitalism develops and governments become increasingly interested in learning about the natural resources of the territories under their control and exploiting them in search of raw materials to increase their economic power.

In this atmosphere of great change, botanical gardens and natural history museums were opened, botanical expeditions were financed, and botany as a scientific discipline underwent rapid development.

Botanical knowledge became transnational and contributions and exchanges among European naturalists increased.

The Age of Enlightenment

The 19th century saw the systematization of scientific language and classification (with the initial contributions of Joachim Junguisfollowed by John Hay Y Carl Linnaeus), the theory of the evolution of species and natural selection was launched, by Charles Darwin and A.R. WallaceThis stimulated advances in plant anatomy, plant physiology and the first phylogenetic system (Engres, 1892), which is the universal reference base in herbaria.

These efforts, by expeditionary groups, financed by governments or individuals, made it possible to learn more about the territory of the Amazon basin, to draw up maps of the regions and the course of the rivers to define boundaries, and to collect plant and animal material, often unknown to science, which was then dominated by Europe.

The late arrival of ethnographic studies.

However, at that time there was little information about the native Amazonian indigenous communities and their cultures.

We would have to wait until the 20th century, with the development of social anthropology and ethnology, and the great contributions of social scientists such as Claude Lévi-Strauss, and other anthropologists and archaeologists, particularly French and American, as well as specialists from the countries comprising the Amazon basin.

Many of them collaborated in the publication of the five volumes of the magnificent Guía Etnográfica de la Alta Amazonía, directed by Fernando Santos-Granero and Federica Barclay, and sponsored by IFEA, FLACSO Ecuador and the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute.

Great men of science in the Amazon during the 18th – 19th centuries

Each of the naturalists, scientists and explorers who ventured into the territories of the Amazon basin deserves a special section to account for their contributions.

However, in this part we will only refer, briefly, to the voyages of La Condamine, Rodrigues Ferreira, Humboldt, Edwards, Wallace, Bates and Spruce.

In this case we will make an exception, an honorable exception, and we will include two great scientists of the 20th century: Schultes among the botanists, and Lévi-Strauss among the anthropologists.

Charles-Marie de La Condamine (1701-1774)

Charles-Marie de La Condamine (1701-1774) was one of the most prominent travelers who visited the Amazon, along with the German Humboldt and the Englishman Wallace. La Condamine was a French naturalist, biologist, mathematician and explorer.

He arrived in Quito, Ecuador, in 1735, as part of the French Geodesic Mission, commissioned by the French Academy of Sciences to measure the length of one degree of the Earth’s meridian on the equatorial line, to put an end to the controversy over the shape of the Earth, whether it was flattened in the center or at the poles.

Having accomplished this objective, La Condamine went deep into the Amazon jungle until 1744. Between 1743 and 1744, he went down the Amazon River, from Jaén, in Bracamoros, to Belém do Pará, looking for proof of the existence of the Amazons, the warrior women mentioned by the chronicler Gaspar de Carvajal, who accompanied Francisco de Orellana.

On his return to Paris, he spoke about, among other things, the rubber tree and its potential uses; about the cinchona plant to extract quinine, a remedy against malaria; and about curare, a strong muscle relaxant used by the Indians for hunting. La Condamine was also known for establishing the foundations of the Decimal Metric System.

Alessandre Rodrígues Ferreira (1755-1815)

Alessandre Rodrígues Ferreira (1755-1815), was a Brazilian naturalist, who directed the Expedicao Philosophica do Pará, Rio Negro, Mato Grosso and Cuyabú.

Rodrígues worked at the Royal Museum of Ajuda, in Portugal.

In 1780 he became a member of the Royal Academy of Sciences of Lisbon.

In September 1783 he left Lisbon for Brazil to collect materials to enrich the Royal Museum of Lisbon, and to make a diagnosis of the situation of the Portuguese colony.

For his venture he received advice from Domenico Vandelli, a leading Italian botanist. He arrived in Belém do Pará in October 1785, and spent the next nine years exploring north-central Brazil, navigating the Rio Negro.

He compiled a large collection of Amazonian species and geological samples, which were extracted from the Royal Museum of Natural History in Lisbon, taken by French scientists as spoils of war, after the occupation of Lisbon by Napoleonic troops.

Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859)

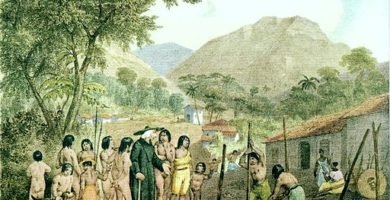

Baron Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859) was one of the greatest modern generalists who visited, albeit briefly, the Amazon, devoting more of his time, together with his friend Aimé Bonpland, to travel the Orinoco region, trying, among other purposes, to establish its connections with the Amazon basin.

He arrived in Lima in 1802, coming from Quito, together with Carlos Montúfar from Quito, to embark on a voyage navigating the course of the Marañón River, up to the entrance of the low Amazon jungle, to stay two weeks in localities of the upper Marañón.

His extensive Journey to the Equinoctial Regions of the New Continent, comprising 30 volumes published between 1805 and 1834, was one of the major contributions to the development of botanical geography, considered the basis of modern biogeography.

William Henry Edwards (1822-1909)

The American entomologist and coal mining entrepreneur William Henry Edwards (1822-1909) was a great butterfly specialist. In 1846, together with a relative living in Argentina, he visited the Brazilian Amazon and was impressed by the regional biodiversity.

He visited the island of Marajó, at the mouth of the Amazon, and sailed the great river from Belém do Pará to Manaus.

He made brilliant observations on the life of butterflies, about which he wrote several books. Noting, in particular, the varied polymorphism of their wings, considered an indication of natural selection.

As a result of his research, he published, in 1847, the book A Voyage Up the River Amazon with a Residence at Pará, which was very well received by the English scientific community, with whom Edwards maintained contacts.

His book was read with great profit by two young Englishmen interested in entomology, Henry Walter Bates (1825- 1892) and Alfred Russell Wallace (1823-1913).

Henry Walter Bates (1825- 1892) and Alfred Russell Wallace (1823-1913)

The two traveled together to Pará, in the Brazilian Amazon, in 1848, and managed to assemble large collections of insects.

Wallace returned to England in 1852, but unfortunately lost his collection in a shipwreck. Bates continued his research in the Amazon until 1859, returning home with more than 14,000 specimens, of which nearly 8,000 were insect species new to science.

Bates is known for describing the phenomenon known as “Batesian mimicry”, whereby of two or more species similar in appearance, one non-poisonous species copies the coloration of the other poisonous or dangerous species, which resembles it, to scare off predators and avoid being eaten by them.

In 1863 Bates wrote The Naturalist in the River of Amazon, consisting of two volumes.

The theory of evolution: Wallace or Darwin?

Wallace, the more recognized of the two, was very interested in the theory of natural selection, of which he was later, along with Charles Darwin (1809-1882), one of its postulants in 1859, although both did so independently.

He was very interested in the idea of transmutation, by which one species is transformed into another. He put forward the river barrier hypothesis: a large river acts as a barrier in the process of species evolution.

By 1855 he had already advanced his theory of natural selection, which he corroborated in trips to the Malay Archipelago, from where he wrote to Darwin.

The idea of the relationship of geographical factors as a cause of selection is Wallace’s, while Darwin was more interested in divergence caused by the adaptation of different populations.

Wallace’s observations on Amazonian life are very acute: on the rubber trade before the peak of its collection, the different colors of the waters of the rivers, their causes and their ichthyological richness, the distribution of species in the Amazon and their endemism, and the description of certain cultural behaviors of the indigenous inhabitants of the margins of the Vaupés River.

Richard Spruce (1817-1893)

Richard Spruce (1817-1893) was an English physician and naturalist who explored the Amazon in 1850 and became interested in medicinal and psychoactive plants. In particular, due to the effects of the ayahuascaThe best known basic combination of the mixture of two plants, ayahuasca, is a compound concoction, Banisteriopsis caapiThe leaves of the chacruna, a vine of the malpigiaceae, and the leaves of the chacruna, Psichotrya viridisThe most well-known combination is the rubiaceae, although there are many other additive plants that are mixed with ayahuasca.

Spruce sent a box of specimens of B. caapi to the Royal Botanical Gardens Kew, London, and made several direct experiments with the concoction between 1854 and 1857.

The naturalist also elaborated the first scientific report on the use of yopo, Anadenathera peregrina, which had been mentioned in reports by chroniclers in 1571, a powerful alkaloid that is inhaled through the nose in the ritual ceremonies of some Amazonian indigenous groups, such as the Guahibo, of the Orinoco River.

Spruce spent 15 years acting as a private collector and agent for the British government. In his obituary for Nature in 1894, his friend A.R. Wallace wrote: “He was a man who, however depressing were his conditions or surroundings, made the best of the life”.

Richard Evans Schultes (1915-2001)

Richard Evans Schultes (1915-2001) is considered the greatest American ethnobotanist related to the Amazon.

When he was a child, he read a book by the English naturalist Richard Spruce, and knew from that day on that what he wanted in life was to dedicate himself to the study of medicinal and psychoactive plants.

It was a life devoted to the development of ethnobotany, of which he was considered one of the major exponents and promoters: director of the Harvard Botanical Museum (1970-1985), founder of the Botanical Society and editor, from 1962 to 1979, of the Journal of Economic Botany.

Before settling in Colombia, Schultes studied the hallucinogenic use of peyote and other mushrooms in the United States (Oklahoma) and Mexico.

He then spent almost 12 years, between 1941 and 1952, in the Colombian Amazon living with indigenous native communities, such as the Cofan, collecting medicinal plants and studying their pharmacological uses, as well as the uses of psychoactive plants by shamans.

He became interested in the effects of curare (Chondrodendron tomentosum), and of its many producing plants, from which d-tubocurarine, a powerful muscle relaxant, is extracted, and of ayahuasca (which combines Banisteriopsis caapi and Psychotria viridis), source of harmines, which inhibit the action of the MAO (monoamine oxidase) enzyme, the former, and of tryptamines, the latter, which produce hallucinogenic effects, metabolized by the action of MAOs.

During his 12-year stay in the Amazon, he identified 1,553 medicinal or toxic species, of which more than 300 species were new to science. One of his books, Plants of the Gods, written with biochemist Albert Hofmann, published in 1979, is considered a seminal work on the history of entheogenic or psychoactive plants.

Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908-2009)

The Frenchman Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908-2009) is the foremost contemporary anthropologist and ethnologist. After his university studies in Paris, where he graduated in philosophy in 1932, he traveled to Brazil as part of a French cultural exchange mission between 1935 and 1939.

During this time he explored the Mato Grosso and other parts of the Brazilian Amazon and was also a visiting professor of sociology at the University of Sao Paulo. He returned to Paris on the eve of World War II.

At the outbreak of the war, he traveled to Martinique, and from there to the United States, residing in New York, where he taught at a university and met other exiles, among them Jakobson, a specialist in linguistic structuralism.

In 1948 he returned to Paris, received his doctorate in Literature and entered French academic life (CNRS, the Maison de Sciencies de l’Homme and the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Studies). He wrote his first book “Tristes Trópicos”, 1955, in which he recounts his Brazilian experience, in the form of a book of short stories, which launched him to fame.

This was followed by his Mythological series of four volumes, published between 1964 and 1971.

Since then, he has devoted himself to the field of structural anthropology applied to the study of myths, kinship and other social relations.

The human mind for Lévi-Strauss

For Lévi-Strauss, the human brain orders the conceptions of the world in the form of structures or systems to interpret the world and understand it. Experience is thus interpreted, with a universal logic that can present different models or systems for the analysis of myths, beliefs and practices.

The anthropologist’s mission is to explain this logic within a particular cultural system. Lévi-Strauss analyzes cultural beliefs and practices by applying structuralism, resorting to the way language is structured and linguistic classification is produced, to explain the construction of human thought and culture.

In this way he constructs a theory of myth, employing a structuralist approach, identifying universal oppositions (such as death-life, nature-culture, raw-cooked, etc.) to organize beliefs and practices about the world.

His theory of kinship is based, not so much on descent from a common ancestor, but on the politics of family alliances, through marriage, which privileges exogamous relationships to strengthen lasting relationships, avoiding the incest taboo, and resorting to the elements of exchange and reciprocity in human relationships.

Bibliography consulted

- Alzate, B. (1993). La ideología de la revolución francesa y los viajeros por Amazonía, 45-62, in: Zea, L. (Coord.). Latin America in the face of the French Revolution. Mexico: UNAM.

- Archila S. The legacy of Richard Evans Schultes and ethnobotany in Colombia. Bogotá: Luis Ángel Arango-Banco de la República Library. https://www.banrepcultural.org./la- amazonia-perdida-0050html.

- Aso Poza U. Claudio Lévi.Strauss biography.psicologíaymente.com/biografías/claude-levi-strauss .

- Funes E.A., Goncalez A. (2012). The recreation of the Brazilian Amazon through travelers, 1-32. 2012_capliv_cafunes.pdf.

- Murari L. (2016). A jungle of adventure and mystery: Amazonian expeditions in Brazilian literature of the 1920s and 1930s. History and Society, No. 33, 111-133.

- Gamboa-Gaitán M.A. (2016). History of botany, 23-49. In: Botánica General: introduction to the study of plants. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

- Kidder D.P. (1980). Reminiscences of travels and permanences in the provinces of the North of Brazil. Sao Paulo: EPUSP. Belo Horizonte: Itatiaia.

- Otero, P.A. Richard Evans Schultes: explorer, scientist and teacher. Revistaboletinbiologica.com.ar/pdfs/N31/historia 31.pdf.

- Pulgarín Reyes M. (2002). Amazonauts of the 19th century. The Amazon space conceived by travelers. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Faculty of Human Sciences.

- Rodriguez-Garcia M.E., Costa A.M. (2016). Hidden relationships at the end of the 18th century: the Specimen Florae Americae Meridionales (1780) of the Royal Botanical Garden of Ajuda and the scientific designs of the Royal Botanical Expedition to the Peruvian Viceroyalty. Asclepius. Journal of the History of Medicine and Science. 68 (1), January-June.

- Schiebungen, L. (2004). Plants and Empire. Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World.Cambrigde, M.A.: Harvard University Press.

- Valcuende del Río J.M. (Coord.). (2012). Travelers, tourists and indigenous populations. STEPS. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Heritage, No. 6.

- Ventura A. (2016). Travelers and naturalists (15th-19th centuries, Europe-America) or how to travel without precautions on a torrential subject. Accueil, ELOHI, No. 9.

Related Posts

January 8, 2020

1. The Conquerors and colonizers of the Amazon Rainforest

January 11, 2020

2 . Missionaries in the Amazon Rainforest (17th century)

January 13, 2020

3. The Utopia of the Earthly Paradise in the Amazon Rainforest

January 19, 2020

5 . The rubber barons between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century.

January 19, 2020

6 . Adventurers behind the Lost City of Z: the true story

January 20, 2020

7. The Amazon Rainforest today (XXI Century)

January 8, 2020

History of the Amazon Rainforest Explorers

This post is also available in:

![]() Español (Spanish)

Español (Spanish)