The exploitation of the rubber tree from the last quarter of the 19th century in the Amazon presents a double reading:

One related to the capitalist technical progress for the global automobile industry, and the process of expanded reproduction of capital for the enrichment of a small and unscrupulous elite, known as the rubber barons.

And another reading loaded with death.

The exploitation of the rubber tree: progress and genocide hand in hand.

The one of progress is inscribed in the need, first, to offer tires for the nascent automobile industry during a very rapid expansion, and then, two decades later, in the need to attend to the transport of military troops during the First World War (1914 -1918).

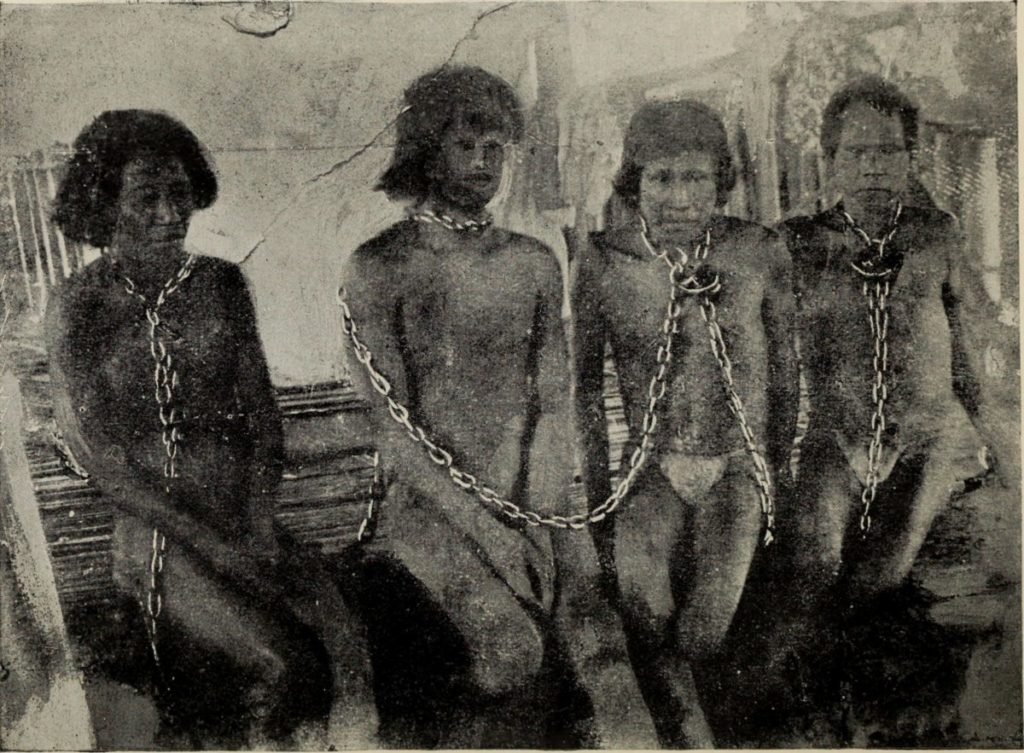

The other story, that of the exploitation and genocide of the indigenous peoples who extracted the product, took place in the jungles of the Amazon basin where the wild rubber tree ( Hevea brasiliensis ) was grown, and which was, among other uses, the natural raw material used to make car tires.

The two stories, that of industrial progress and that of the exploitation of Amazonian indigenous peoples, were mediated by the greed and cruelty of businessmen who, using armed foremen, employed inhumane methods to enrich themselves by sowing terror and death in the Amazon.

The first rubber fever (1879-1912)

The exploitation of rubber at the end of the 19th century meant a time of great prosperity for the rubber barons and the Amazonian trade as the nascent automotive industry developing in Europe and the United States demanded more and more rubber to produce tires.

This growing demand for the raw material caused its price to rise and caused the consolidation of some Amazonian regions where the rubber was extracted, and of some Amazonian cities from where it was exported.

During that period a massive incursion began of many settlers and workers in the Amazon jungle, following the course of the main navigable rivers, in search of native rubber.

At that time cities grew and became rich in the middle of the jungle, such as Belem and Manaus in Brazil , and Iquitos in Peru. Those cities were modernized with the first public services and ostentatious urbanism.

Manaus was the most prosperous city in Brazil: the only one that had electricity networks and a sewage system. It had 15 km of electric tram line.

In a region where the law of the strongest prevailed, it boasted of having, in the middle of the jungle, large and dazzling buildings, such as the Amazonas Theater (1897) and a majestic Palace of Justice.

Author: Karine Hermes ( CCby4.0 )

There were luxurious brothels with prostitutes brought from Paris or Baghdad. Researchers point out, for example, that a 13-year-old virgin Polish girl was offered for $400.

The excess reached such a point that the dirty clothes of the rubber barons were sent to London or Lisbon to be washed.

Something similar, but of smaller proportions, happened in the Peruvian city of Iquitos, with its large mansions, such as the Morey house, or the rise of the Iron House which, apparently, was designed by the Frenchman Gustave Eiffel.

Source: DiverDave [CC BY-SA 3.0]

Source: DiverDave [CC BY-SA 3.0]

That conspicuous consumption eventually crumbled, false prosperity deflated, and cities stagnated — a decline that historians attribute to two main causes.

Rubber tree biopiracy

The first was that the British had illegally extracted seeds from the Brazilian rubber tree, the first notable and well-documented case of international biopiracy, and had propagated and planted those seeds over large areas of Ceylon, British Malaya and sub-Saharan Africa, substituting the supply of Amazonian rubber with the cheaper rubber produced in the British colonies.

Some 70,000 Amazonian rubber seeds were stolen in 1873 by British explorer and agent Henry Wickham.

Source: Luis Fernández García ( cc-by-sa-2.5-es )

Of that total, only 4% of the total survived. In 1876 some 2,000 seeds were planted in the British colonies of Ceylon and Singapore. And then other seeds were sown in the Dutch East Indies, now Indonesia.

By 1898 there was also a large rubber tree plantation in Malaysia. Rubber production in Asia expanded because the plants had higher productivity than those in the Amazon.

These were renewed plants, genetically improved and in large, well-planned plantations, offering a product at a lower cost than the Amazonian version.

And prices fell globally. Purchases of Amazonian rubber were reduced and replaced by cheaper Asian rubber because the Asian product did not have to travel long distances through the jungle to be marketed, and there were efficient railways and ports close to the production sites. .

Thus, the extraction economy in the Amazon collapsed, in what has been called the first rubber boom.

Synthetic rubber

The second cause of the decline of the foreign trade of Amazonian rubber in its first stage was the invention of synthetic rubber, which began replacing natural rubber around 1925.

Synthetic rubber was the result of many advances that began in 1879 by Bouchardat, until it was perfected in 1940 and marketed under the name Ameripol.

In that first period, rubber was extracted not only from the Amazon jungle of Brazil, but also from Bolivia, Peru, Colombia, Ecuador and Venezuela.

In Peru, the center of the boom was Iquitos, Tarapoto, Moyobamba, Pucallpa, Lamas and Leticia (then belonging to Peru).

In Iquitos, large mansions were built and the lifestyle of the rubber tappers and urban dwellers changed, while the indigenous people became increasingly miserable.

Beneficiaries of the exploitation of rubber in the Amazon

The great beneficiaries of the rubber trade were the commercial houses, such as those of Julio César Arana, Luis Felipe Morey and Cecilio Hernández.

Source: Courret study. Lima, c. 1912 [Public domain]

Casa Arana was the most powerful. Associated with an English company, it went on to become the Peruvian American Company, with headquarters in London and shares on the Stock Exchange. It extended its domain to the Colombian rubber zones of Putumayo, where Casa Arana had begun to operate in 1904.

In Bolivia, rubber had been exploited since the 1870s in some areas of the upper course of the Beni River, the Madera and the lower Mamoré.

In 1880, following the discovery of the confluence of the Beni and the Mamoré, and its connection with the Amazon, the exploitation of rubber spread rapidly to the north, facilitating the migration of Creoles and mestizos to the interior of the Beni territory, and forcibly incorporating indigenous labor for the harvest.

There, in the Beni, the Casa Suárez Hermanos dominated, using the same procedures of subjugation of the indigenous people that the system of debt slavery advocated.

The rubber tree

The rubber tree ( Hevia brasiliensis ), or seringueira in Portuguese, is a tree 20 to 30 m tall, with a straight, cylindrical trunk about 30 to 60 cm in diameter, with light white wood. It belongs to the Euphorbiaceae family.

A white liquid or latex, also called rubber, which is composed of 35% hydrocarbons, is extracted by incision from its thick stem.

Latex is a substance with a neutral pH of 7.0 to 7.2, but if it is allowed to dry for more than 12 hours, the pH drops to 5, and it coagulates spontaneously, forming a polymer known as rubber.

However, it acquires impurities and becomes very perishable and prone to decomposition. To avoid this problem, the rubber is heated and vulcanized. Vulcanization is a process, discovered in 1839, in which rubber is heated, along with the addition of sulfur, to harden it and make it more resistant.

The additive modifies the composition of the polymer, forming crosslinks or bridges between the different polymer chains. In this way the rubber becomes resistant to solvents and changes in ambient temperature.

The latex or rubber is obtained from several plant species, such as Castilloa elastica, Gutapercha palaquium, Ficus elastica, etc., but the preferred one, due to its quality, was the Hevea brasiliensis species.

The second rubber rush

The rubber boom began in 1879, mainly in the Brazilian Amazon, and spread until 1912 to other Amazonian countries, such as Peru, Bolivia, Colombia, and Venezuela, where the rubber plant grew wild.

In 1942 there was a second rubber boom that lasted until 1945, due to the incidents of World War II (1939-1945).

Manaus, on the banks of the Negro River in the Brazilian Amazon, was the main port for the export of rubber obtained in Brazil, Peru, Ecuador, and Bolivia, and for harvested Brazil nuts ( Bertholletia excelsa).

Indigenous labor was used for the rubber production, and payment was not exactly in the form of a salary (which was perhaps of little interest to the economy of the native communities, with little contact to urban settlements and the market), but rather in the form of exchange for utensils, weapons, tools and clothing, which merchants delivered at an increasingly higher price. These exchange items were delivered in advance and then the debt owed was deducted with the delivery of the rubber product, which was poorly weighed and subject to an ever lower market price.

Thus, an unpayable debt was generated, promoting debt slavery, from which the indigenous peoples were never freed, and was the basis for a system of personal subjection to a relationship of cruel exploitation.

That was the economic system applied by the great rubber exporting houses, such as that of Julio César Arana (1864-1952), the most cruel and powerful of the rubber barons, who had his family residence in a luxurious mansion in London. Another important exporting house was that of Carlos Fermín Fitzcarrald (1862-1897).

Manaus port was, around 1914, the main outlet for Amazon products to the Atlantic Ocean. Amazonian products arrived there from the Peruvian jungle, both rubber and Brazil nuts or chestnuts. They came from Loreto, with its capital in Iquitos, or from the department of Madre de Dios, whose capital was Puerto Maldonado, and products were also received from neighboring Bolivia and Brazil itself.

November 25, 2019

Brazil Nut (Bertholletia excelsa)

The Madeira-Mamoré railway was also used. With rail length of 364 km, it was begun in 1907 and completed in 1912 under the direction of the American businessman Percival Farquhar.

The fall in the price of Amazonian rubber, the competition of the Panama Canal (active since August 1914) and the heavy rains in the region eventually condemned the railway, reducing it to its minimum scale by 1930. Today only 7 km remain in operation for tourist purposes.

The indigenous people who collected the latex were obliged to deliver a certain weight to the merchants. If they did not, they suffered punishments and even mutilations of parts of their bodies, all to instill fear in the others and to reinforce the obligatory nature of the commitment. To dominate the indigenous groups, the rubber barons hunted them down and forcibly removed them from their lands to the rubber tree-producing regions to live with ethnic groups from other cultures.

In the Putumayo river basin alone, 40,000 indigenous people died, out of the 50,000 who inhabited it at the beginning of the 20th century.

The extraction of Amazonian rubber reached its minimum levels in 1912 as it was replaced by Asian rubber. But the evolution of the events of World War II created a second chance for the economy of the Amazon.

The Japanese forces, aligned with Germany against the Allies, invaded Malaysia, the South Pacific, and other rubber areas. Under Japanese control, the supply of Asian rubber to England was cut, producing a great shortage in the Allied countries.

The United States and England then looked towards Brazil, presided over by Getulio Vargas, and established the Washington Agreement.

Brazil promised to increase its production from 18,000 tons to 45,000 tons in a campaign of intervention in the Amazon known as the “rubber battle.”

Meeting that goal required the recruitment of 100,000 workers and its operations center was established in the city of Fortaleza, in the northeast of Brazil.

The company was organized by the Special Service for the Mobilization of Workers to the Amazon (SEMTA). The expenses caused by the transfer, equipment, and food of this enormous contingent of workers were financed by the Rubber Development Company (RDC), at a cost of 100 dollars for each worker who arrived to sign up to work in the Amazon.

Most of the workers came from the Brazilian state of Ceará in the northeast. From that enormous effort, a kind of epic was created that described the workers as “rubber soldiers.”

The economies of Manaus, Belén and other Amazonian cities were strengthened. However, in the end, once the great war ended in 1945 and the objectives were met, many workers never returned home: some 30,000 died from malaria or hepatitis, or did not survive the dangers of the jungle; and the others, the majority, were abandoned to their fate in the Amazon.

The illustrated epic of rubber

Much literature has been written about the dramatic history of the exploitation of rubber and of the Amazonian indigenous people — from the famous costumbrista novel La Vorágine, by the Colombian novelist José Eustacio Rivera, to novels by contemporary writers such as Alberto Vázquez-Figueroa, with his Manaus, or The Celt’s Dream, by the Peruvian Mario Vargas-Llosa, Nobel Prize winner of literature.

The history has also served as a theme for some great film productions, such as the exceptional Fitzcarraldo in 1982, by German director Werner Herzog, starring Klaus Klinski. Or the valuable Colombian 2015 film The Embrace of the Serpent, by director Ciro Guerra, filmed in the Colombian Amazon to tell the story of two nature scientists.

One of them, Richard Evans Schultes, is considered the greatest Amazonian botanist of the 20th century. In the background of these films and literary works is the bloody exploitation of the rubber tree in the jungle and the great suffering inflicted on the Amazonian indigenous people.

This post is also available in:

![]() Español (Spanish)

Español (Spanish)