Mining is a trade that has been practiced irregularly in Venezuela for decades. Attempts to regulate this activity have been half-heartedly respected; the laws regulating this activity are constantly violated by the groups that control the extraction of minerals illegally in the country.

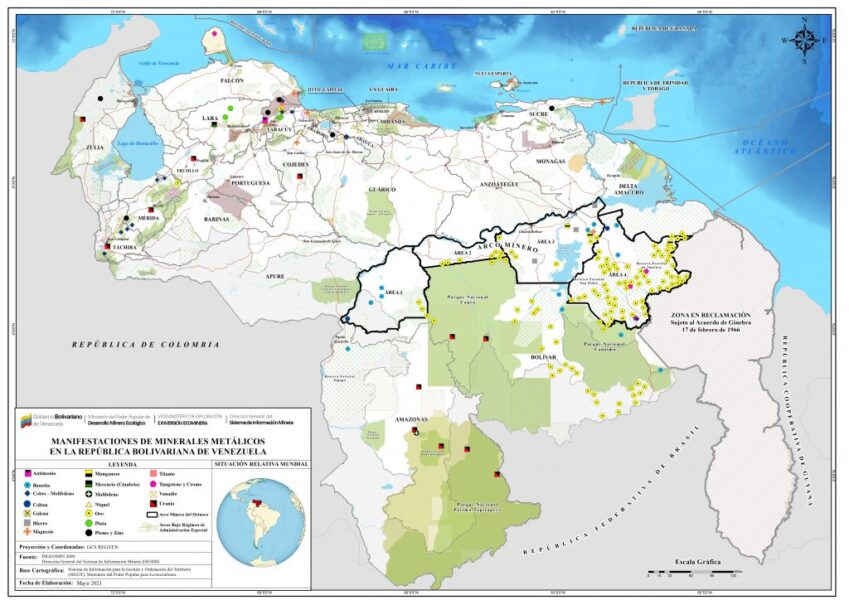

According to Provita, in the last 20 years mining activity has doubled in the Venezuelan Amazon, even reaching protected areas such as Canaima National Park. By the beginning of 2020, 1,033 hectares had been affected by illegal miners.(1)

The toxic footprint of mercury in Gran Sabana

Mercury is a chemical that is among the 10 most harmful substances of greatest concern to the World Health Organization (WHO).

In 2020 the non-governmental organization SOS Orinoco was able to determine through field research conducted among a portion of the indigenous population living in Canaima National Park, that at least 35% of the samples taken showed some mercury levels that exceed the value limit established by the WHO.

Mercury is used by the miners for the final process of extracting the small gold particles, as these are bound to the mercury and then burned to obtain pure gold.

This process involves direct contamination by the miner who handles the mercury and then inhales the vapors in the gold purification phase.(1)

Effects of mercury on the human body and the environment

Mercury is a highly volatile chemical that is easily biotransformed, and its rapid mobility and dispersion make it a particularly dangerous poison that attacks the ecosystem where it is dumped, affecting the species on which the people living in mining areas feed.

According to Conservation Strategy data, 2.6 kilos of mercury are needed to extract one kilo of gold. Of this amount, 13% is poured into rivers, 3% is absorbed by fish and can travel up to 2000 km dispersing the contamination.

Mercury damage in humans ranges from tremors to neurological damage, as well as damage to internal organs, respiratory system, reproductive system and vision.

The most vulnerable are children and women. If they are pregnant, contamination is transferred to the fetus, according to WHO studies.(2)

The Amazon in dispute: political agencies and indigenous organizations of the Venezuelan Amazon facing the Orinoco Mining Arc.

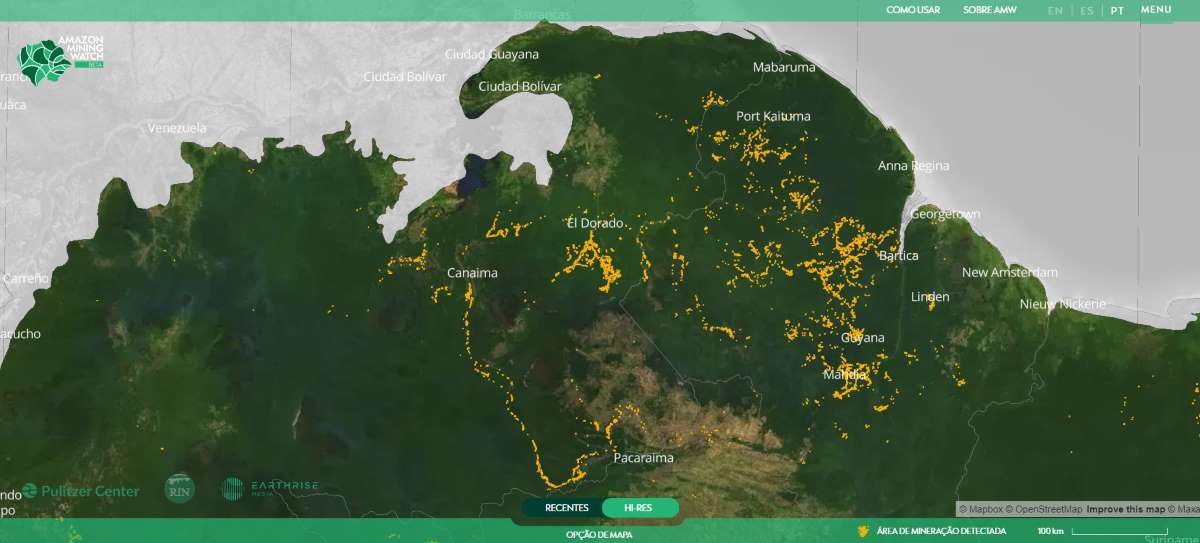

The Orinoco Mining Arc was created in 2016 with the purpose of addressing the fall in oil prices, through the exploitation of minerals located in the Venezuelan Amazon territories equivalent to 12.2% of the national territory.

At least 13 indigenous communities live in this area. The Warao, Akawayo, E’ñepa, Pumé, Mapoyo, Kariña, Arawak, Piaroa, Pemón, Ye’kwana, Hoti, Jivi and Sanemá.

The Arco Minero del Orinoco (AMO) meant that many of these indigenous ethnic groups that inhabit the territories where the state allowed mining exploitation, broke the relations they had achieved so far with the Venezuelan state.

The indigenous people are organized in different groups, which to a greater or lesser extent feel defrauded by the government. This division of opinion is summarized as:

- Groups that oppose the economic policies of the Arco Minero del Orinoco but maintain a relationship with the state,

- Those who were somehow captured by the government’s power and ideological factors and who, contrary to the natural defense of their lands, support the development of the Orinoco Mining Arc,

- The groups that allied themselves with the traditional opposition parties,

- And those who remain totally outside of any project that harms their land.

These positions have had a flexible character within some indigenous groups, which is taken as a result of the break with the ideological thinking of the current Venezuelan government, which in its beginnings had the majority support of the indigenous movement.(4, 5)

Area planned for mining production in the Arco Minero del Orinoco. Source: Ecomineria, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

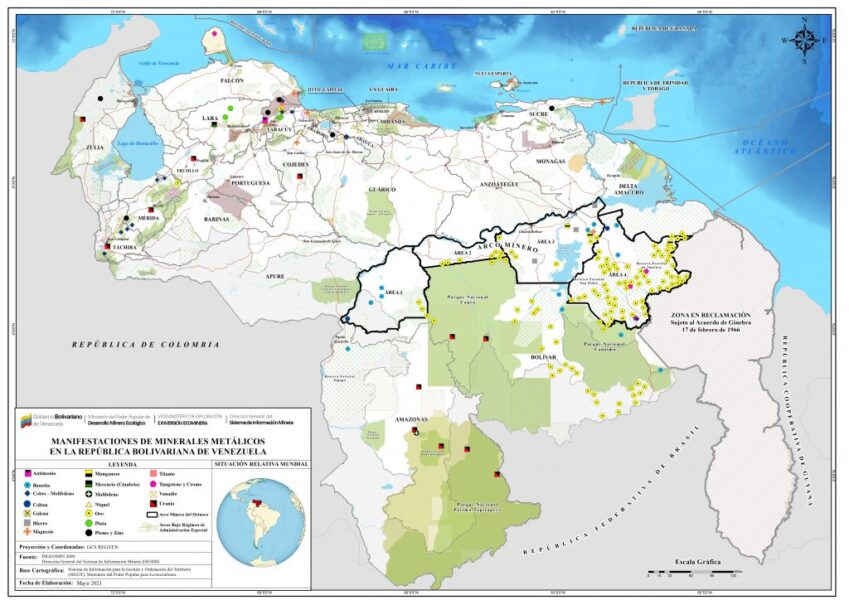

Design and development of a Geographic Information System (GIS) on illegal mining in Venezuelan Guyana

Illegal mining is a reality present in large areas of the Amazon and covers several countries, so it is relevant to highlight the damage suffered by this heritage of the world’s ecology.

In the case of Venezuelan Guyana, studies were carried out in the Areas under Special Administration Regime (ABRAE), indigenous territories and watersheds. For the study, a Geographic Information System (GIS) was created based on official maps and the digitalization of areas with illegal mines, clandestine airstrips, untitled indigenous areas, concluding with the Orinoco Mining Arc area.

The study estimates that 6.19% of the Areas Under Special Administration Regime are taken by illegal miners in addition to 900 km2 belonging to National Parks, 11 watersheds with an average of 700 km of rivers and 1.08% of indigenous territories.

There are at least 189 mines located in the states of Amazonas and Bolivar, of which at least 57 are less than 40 km from clandestine airstrips that facilitate the aerial extraction of strategic materials.

In the planning of the Orinoco Mining Arc, 79.71% of illegal mining is not recognized, so this policy would not be the definitive solution to the problem and would only contribute to a slight reduction. It is also true that it would increase the production of minerals in a legal manner, but without quantifying the possible damage to the ecosystem. (6)

Sources (in order of citation)

- Ramírez, M. (2021). The toxic footprint of mercury reached the Gran Sabana. Correodelcaroni.com. Retrieved April 4, 2022, from https://especiales.correodelcaroni.com/la-huella-toxica-del-mercurio-llego-a-la-gran-sabana/.

- SOS Orinoco (2021) Mercury and mining in Venezuelan Guyana. SOS Orinoco. Retrieved April 4, 2022, from https://drive.google.com/file/d/1WiqjQdRz6Cx_v5J-5S4p3jIT72Fb-f6R/view.

- Heck, C. (2014) The reality of illegal mining in Amazonian countries. Peruvian Society of Environmental Law SPDA. Retrieved April 4, 2022, from https://repositorio.spda.org.pe/bitstream/20.500.12823/274/1/Realidad_mineria_ilegal_2014.pdf.

- Silva, J. M., & Velásquez, F. R. (2019). The Amazon in dispute: political agencies and indigenous organizations in the Venezuelan Amazon facing the Orinoco Mining Arc. Polis, 52. https://journals.openedition.org/polis/16668

- Ruiz, F. (2018) The Orinoco Mining Arc. New Society No 274, March-April 2018, ISSN: 0251-3552. Nuso.org. Retrieved April 4, 2022, from https://static.nuso.org/media/articles/downloads/9.TC_Ruiz_274.pdf.

- Vanessa, J., Rosario, N., & Álvarez Flórez, V. (n/d). DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT OF A GEOGRAPHIC INFORMATION SYSTEM (GIS). Uniovi.es. Retrieved April 13, 2022, from https://digibuo.uniovi.es/dspace/bitstream/handle/10651/42150/TFM_Jennire_V_Nava_R.pdf?sequence=6&isAllowed=y.

Gerson Alvarado, Comunicador Social egresado de la ULA Táchira, Venezuela. Actualmente desempeñando funciones de Comunicador y Reportero Audiovisual. Fotógrafo, Músico y Ciclista. Apasionado por captar imágenes de paisajes y documentar historias.

This post is also available in:

![]() Español (Spanish)

Español (Spanish)