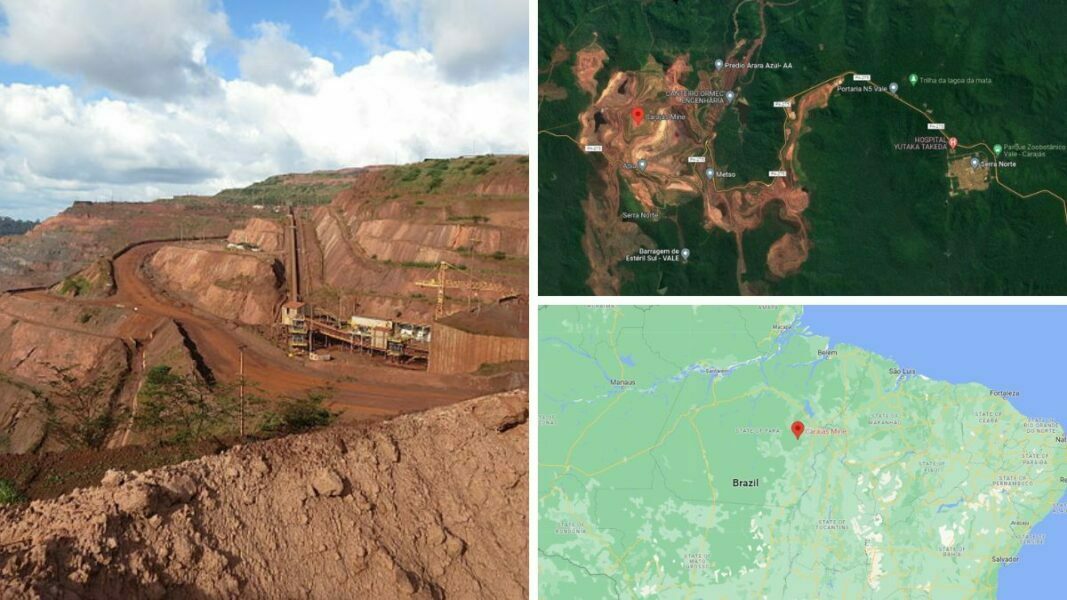

The largest iron ore mine in the Amazon is called Carajás, located in the state of Pará, in northern Brazil. It was discovered in 1967 and is considered the largest iron ore reserve on the planet. The value of its production is currently estimated at US$13 billion.

Vale is the company that manages the exploitation of iron ore, the second largest mining company in the world, which considers the Carajás mine to be the largest mining project in history. Its reserves are estimated at 18 billion tons of iron ore, and it also has deposits of nickel, copper, manganese and gold.

The Carajás mine has an annual production of approximately 110 million tons of iron ore, which represents 35% of the company’s iron ore production.

Vale’s mines are located within the Floresta Nacional de Carajás environmental reserve. Created in 1998, it is considered a conservation unit and has 411,000 hectares. Of this area, some 104,000 hectares are dedicated to mining and its administration was ceded to Vale in conjunction with the Chico Mendes Biodiversity Conservation Institute. (1)

IUCN Category VI (protected area with sustainable use of natural resources). Source: IsabeleC, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Vale mining company between environmental responsibility and abuse

Access to the reserve is controlled by the mining company’s security personnel who act as regional police, and they decide who is allowed to enter. Mine employees must request authorization from the company to receive visitors.

Vale Zoobotanical Park

For press and tourist visits, you are first taken to a zoo that houses species rescued by environmental protection agencies.

Known as the Vale Zoobotanical Park, it was created in 1985 for the care and protection of endangered species of the Amazonian fauna. It has an area of 30 hectares preserved within the Carajás National Forest. It has approximately 360 species, which are distributed among endangered birds such as the harpy eagle, mammals such as the jaguar, puma and various species of Amazon monkeys. (2)

The Carajás mine looks from the sky like an open wound in the middle of the Amazon rainforest. The mining company assures that when the extraction of all the mineral in the area is completed, all the excavated material will be covered again. Environmentalists applaud the good intentions, but are also certain of the irreparable damage to the ecosystems surrounding the mine.

Between 2003 and 2012, Vale was fined by the government nine times for environmental damage.

The metalliferous savannah is the most threatened ecosystem, where the Canga grows, a plant that warns of the presence of iron ore; it is a unique species in the area and has not yet been sufficiently studied(3).

The iron road

This is the name given to the railway that transports the ore extracted from the Carajás mines to the export port of Ponta de Madeira in São Luis, where it is shipped to its main destination: the People’s Republic of China.

The giant Vale train is 3 km long and frequently stops in the middle of the road, hindering the passage of the inhabitants of the areas near the track, and when it leaves again the train does not give any warning, which has caused multiple collisions.

Most of those affected belong to a social movement known as the Landless Rural Workers, which has been in conflict with the company since the invasion of their territory to build the iron road and the resulting accidents that have occurred.

Geny Viana neither his brother’s family nor his family received compensation for the deaths, the company has not put safety measures in place to prevent the train from being run over, and despite its multi-million dollar profits, they only paid for the coffin to bury their loved ones. (4)

A conflict zone

Land conflicts have been the cause of years of protests, the company defends itself and denies any irregularities in the acquisition of land for its development. One of them, known as the Carajás S11D Iron Project, has an investment of 40 billion Brazilian reais that will strengthen the local economy and generate more than 30,000 direct jobs and 15,000 indirect jobs. (5)

The landowners who benefit the most from this money for the purchase of land are the landowners who have legal ownership of the land and also have the economic capacity to negotiate with the company, as opposed to the indigenous populations and the working classes.

Since the 1970s, the mining company has been in conflict with the original inhabitants, who have been the first to be affected, as their way of life has been affected. The company states that it has maintained a technical and multidisciplinary team to attend exclusively and with a respectful relationship that remains long-term with the ancestral peoples located in the vicinity of the exploitation areas.

The footprint of exploitation in Pará continues to expand; it is the leading state in deforestation rates in the Amazon. For 2018, a study by the National Institute for Space Research has calculated that the extent of logging was 2,840 km2. In addition to this, there is river contamination and damage to flora and fauna. (4)

Sources

- From Investigative Journalism, A. P. (2014, February 14). Canaã dos Carajás: Vale’s promised land in Brazil. AméricaEconomía | AméricaEconomía. https://www.americaeconomia.com/negocios-industrias/canaa-de-los-carajas-la-tierra-prometida-de-vale-en-brasil

2. Vale Zoobotanical Park (PZV). (n/d). Vale.com. Retrieved April 20, 2022, from http://www.vale.com/brasil/PT/initiatives/environmental-social/zoobotanic-park/Paginas/default.aspx.

3. The largest iron ore mine in the world is in the Amazon. (2012, June 19). https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias/2012/06/120619_video_brasil_carajas_minas_cch

4. Lives traversed: how the Vale affects the lives of indigenous and landless people in Pará. (2019, February 25). Brasil de Fato. https://www.brasildefato.com.br/2019/02/25/vidas-atravesadas-como-la-vale-afecta-la-vida-de-indigenas-y-sin-tierras-en-para

5. Roberts, T. (1998). Informal sector and local economic spillover in a mining development megaproject in Brazil. Sociológica, 13(37), 99-123. (S/f). Redalyc.org. Retrieved April 20, 2022, from https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/3050/305026610005.pdf.

This post is also available in:

![]() Español (Spanish)

Español (Spanish)