In this article I will deal with the jobo, also known as cajá, ubos, hog plum, or ashanti plum (Spondias mombin). The other species to which I will refer, the jocote or bone plum (Spondias purpurae), will be described on another occasion. Even in that large family, there are other similar species, such as Spondia citherea. Some books indicate even more species equivalent to S. mombin, but perhaps these are redenominations made by botanists. This is probably the case with Spondias auriantiaca, S. axillares, S. dubia, and S. lutea.

My experience with the jobo

(…and how it differs from other similar fruits such as jocote or bone plum)

When I was a child I ate jobos until I almost burst. I ate without heeding the advice of my elders who told me I would get sick because eating it in excess would give me a fever.

The jobo or cajá (as they call it in Brazil) was a very tall tree, and we couldn’t climb it because the bark on its trunk was hard, thick, and had sharp ridges like thorns. As such, to eat the fruit we had to pick it up from the ground.

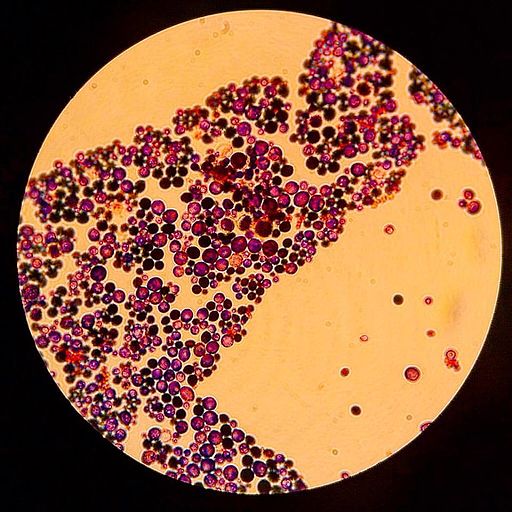

Author: Esteban M. Martínez Salas (taxonomic determination)

Carlos Sergio García Toledo (photograph and collection) Source: http://unibio.unam.mx/irekani/handle/123456789/39034?proyecto=Irekani

When it rained, the fruits fell, and there were jobos or ubos scattered all over the ground, and the pleasant smell they gave off intensified with humidity.

So we all clearly distinguished between the jobo (cajá) and the bone plum, which was my favorite, because its flavor was sweeter and its smell milder.

What does jobo or cajá taste like?

The skin of the jobo is thin and yellow, its pulp has an acidic flavor and is very aromatic, so much so that its smell, at the time of the fruiting of the tree, permeated the air.

The bone plum is very different. Its skin is green or reddish, depending on the variety, relatively thick and resistant, its pulp scarce and firm, the smell pleasant and its taste sweet.

For me there were many differences between the jobo and the bone plum — the size of the tree, the shape of its branches, and the flavor of the fruit.

I do not understand, then, the confusion between these two species, sister plants, but which are so different from each other. However, some who write about these things confuse them.

Scientific name and 36 vernacular names of the jobo, ubos or cajá

The great diversity of vernacular names that jobo has causes confusion in regional descriptions. Here is a list of their common names by country:

- Bolivia: they call it ubos, cedrillo, itahuba.

- Brazil: taperibá, cajá, cajarana.

- Colombia: where it is more widespread in the departments, they call it arisco, plum, warmano plum, Castilla plum, hobo plum, bone plum (creating confusion with S. purpurae), monte plum, jobo, white jobo, Arisco jobo, red jobo (reproduces confusion), Amazon jobo, plum mango.

- Ecuador : they call it obos, ajuel.

- Peru: they call it shungu, shun, ushun, jobo, ubos, sour plums.

- Panama and in Venezuela: jobo, hobo, jobero.

- In Costa Rica, jobo, jocote de jobo, balá or yuplón.

- They also call it in some places plum mango, yellow plum, yellow mombin, orocorocillo.

- In Mexico they call it jocote (again confusing it with common names of S. purpurae).

- Translations:

- In Africa: Ashanti plum, iyeye, ngulungwu, isada

- English: Yellow mombin or Spanish mombin

- French: Prune mombin

- Portuguese: Cajaze ira

Origin and distribution of the jobo or cajá tree

The jobo is native to Central America and northern South America. Some botanists consider that another area of origin could have been the Amazon Basin, due to the abundance of wild plants found in the Amazonian lowland forests.

The geographic distribution of the jobo is very wide. It extends along the coast of the Pacific Ocean as well as the Gulf of Mexico. It then descends from Mexico to the south, crossing Central America and the Caribbean islands, then passing through Panama, Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, and continues until it reaches the Amazonian part of Brazil and Peru.

Throughout this long extension, there are three areas in which it is widely distributed: Costa Rica, Panama and Venezuela.

In addition, the jobo or cajá has been introduced in the tropical regions of Africa and Asia.

Botanical description of Spondias Mombin

Tree

It is a deciduous tree, from the Anacardiaceae family, with an average height of about 25 m, but which can reach up to 35 m.

It is branchless during the first two to ten meters of growth, but later forms a dense crown .

The trunk, which ranges from 0.5 to 2 m in diameter, has a cracked, hard, thick, rough, light brown bark with hard, thorn-like ridges.

From the trunk emanates a whitish and sticky resin, with a bitter taste.

Flowers

They are white or yellow. The female flowers are 8 to 9 mm in diameter.

Source: Tarciso Leão from Saint Paul, MN / CC BY

Leaves

The leaves are 25 to 50 cm long, alternate, pinnate, green to yellowish green on the upper side, and lighter green on the underside, where some soft hairs can be seen.

If the leaves are crushed, a strong mango flavor emanates (the mango also belongs to the Anacardiaceae family).

Fruits

The fruits are presented as infructescences that hang up to 30 cm in diameter, presenting ovoid drupes of about 3 cm to 4 cm by 1.5 cm long by 2 cm wide, small, green or dull orange-yellow in color, which come together in groups of up to 20 units.

It has a cream-colored pulp or mesocarp, small, but juicy, with a bittersweet and highly aromatic flavor.

The endocarp has 3 to 4 seeds.

Half the weight of the fruit is pulp. An adult tree can yield about 100 kg of fruit.

A similar species…

Some botanists associate the species S. mombin with S. lutea, which is abundant in Brazil. It may be a different species or a subspecies of the Brazilian species, although the fruit of the latter is more orange in color and has a better flavor (FAO, 1986).

Agronomic management

The jobo, ubo or cajá is generally found wild, with very little cultivation. It is a heliophytic species that grows very well in a wide variety of environments. It thrives even in rocky and poorly drained soils.

How is jobo planted?

Known as the cajá in Brazil, it reproduces by seeds. It can be propagated by asexual reproduction, which is preferable for speed, by rooting cuttings of mature wood, 50 to 100 cm long, and 5 to 10 cm in diameter. Vegetative propagation by grafting can also be carried out.

Fruiting occurs when the tree is about five years old.

Natural or wild propagation

The seed is dispersed by primates, especially the howler monkey (Alouatta palliata). Birds, bats and deer also act as dispersal agents.

Conditions: soil, climate, altitude…

The plant grows in forests with an average annual rainfall between 1,000 and 2,000 mm and at an average annual temperature between 23 and 28 °C. It is an undemanding species, as is the case with several anacardiaceae, which develops in a wide variety of soils, with a pH between 5 and 7, and even in soils poor in nutrients, or from sandy or clay soils, with poor drainage. It can even be supported in flooded soils for two or three months a year.

It grows in full sun and does not tolerate shaded spaces throughout its life cycle, except in the seedbed period, until its transplant to the field.

Its great adaptability has made the plant an efficient alternative for erosion control and recovery of degraded soils.

Nutritional value of the fruit of the jobo, ubos or cajá (Spondias mombin)

The fruit of the jobo is remarkable in vitamins A and C content, and in some minerals such as phosphorus and calcium.

In an amount of 100 g of jobo pulp, the following values were obtained:

Energy value: 218 calories

Water : 72.8 g

Proteins : 0.6 g of protein

Lipids : 0.1 g

Carbs : 8.7 g

Fiber : 0.6 g

Ashes : 0.4 g

Reducing sugars : 6.7 g

Vitamins

As for vitamins, it has 11.0 mg of ascorbic acid, 70 micrograms (ug) of carotene, 0.5 mg of niacin, 0.67 mg of pyridoxine, 0.05 mg of riboflavin, 6.74 mg of thiamin.

Minerals

The mineral values are as follows: 26 mg of calcium, 27 mg of phosphorus, 2.2 mg of iron.

In other studies the values differ, in some cases significantly: for example: 53 calories of energy value, 12 g of carbohydrates, 20 mg of calcium, 50 mg of vitamin C, 176 mg of potassium and 21 mg of calcium.

Chemical composition

The most interesting part of the jobo plant from the point of view of its chemical composition is its bark .

An aqueous extract obtained from the bark showed some antimicrobial and antifungal activity in the laboratory against pathogenic microbes such as Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus cereus, and antifungal against Candida albicans (Arias, 2000).

A more complete phytochemical study was carried out by Pérez-Portero, Rivero-González, Suárez-López and González-Pérez (2013), in which they examined the root bark, stem bark and leaves of jobo, to determine that the highest presence of tannins and phenols, saponins, coumarins, flavonoids and reducing sugars is observed in the root bark and leaves of the plant.

It is important to point out that the location of the soil and the climate during development of the plant have a direct relationship with the content of phenolic components and the antioxidant capacity of the fruits (Poveda 2014; Cunha-Alves, Cordeiro, Hebster 2001).

Food uses of jobos

The fruit of the Spondias Mombin species is edible as a fresh fruit, although it is more commonly eaten cooked or dried.

It is used especially for the preparation of drinks, juices, soft drinks, jellies, ice cream, jams, and sweets.

It is also used for the production of “wines” and liquors.

The jobito juice (jobo juice, water, sugar and lemon juice) is highly valued in some Colombian regions.

With the agroindustrially processed fruit, a highly valued nectar is produced in some countries, in particular a concentrate that has 18% pulp, with 14 brix and 0.30 titratable acidity, using pulp with 12.2% sucrose and 67.7% water, with a brix/acidity ratio of 46.6 and pH2.9.

In Brazil, the “vinho de tapeiriba” is prepared with the jobo pulp, with a small alcoholic gradation.

In Guatemala, a drink similar to cider is made from the pulp.

Alternative uses of jobos

Apart from food uses, jobo trees are used as posts or living fences (line of trees or bushes that delimit a property), and also as a windbreak, firewood, charcoal, fodder, and fruits and shelter for wildlife.

Jobo wood, despite not being of great quality, is used to make cheap furniture.

It also offers good possibilities as a honey plant for beekeeping development.

The resin that flows from the trunk of the tree is used locally as glue.

More than 10 medicinal uses of jobo

The jobo (complete fruit or pulp, peel, bark, leaves, and roots) is credited with many healing properties.

The leaves are used, for example, to stop bleeding.

The extract of the leaves is used as a diuretic and antispasmodic, and in some parts as an astringent. It is also used as an antiseptic, for its antimicrobial activity, and as a uterine stimulant.

In the Ticuna indigenous ethnic group from the Colombian Amazon, a decoction made with the bark is used as a contraceptive or antiseptic. This decoction is also used as a healing agent.

In Brazil, the decoction made from the bark is used as an emetic in the case of malarial fevers.

The two parts of the plant most used as medicine are the bark and the root.

However, infusions made with leaves or flowers are also used to treat problems of the digestive tract, sore throat, and malaria fever. The leaf decoction is used to cure colds, fever, and gonorrhea.

The pulp consumed in excess acts as a purgative and emetic. Normally consumed, it is used as a relaxant, antiseptic, astringent, refreshing expectorant, laxative and vermifuge.

Bibliography

- Arias G. 2000. Chemical-biological and bacterial determination of Spondias mombin L. Science and Research, Vol. III (2), Lima, National University of San Marcos in Lima. Source

- Blackwell WY Dodson CH 1968. Spondias mombin L. Flora of Panama. Ann. Missouri Botanical Garden, 54(3), 365-367. PDF

- Brack Egg A. 2012. Dictionary of fruits and fruits of Peru. Lima: San Martin de Porres University. Source

- Causeway J. 1980. 143 native fruit trees. Lima: Book. The student. PDF

- Cunha M, Alves R., Cordeiro A, Hebster C. 2001. Quality of native Latin American fruits for the industry: jobo ( Spondias mombin L ). Interamerican Society for Tropical Horticulture, 43, 72-76. PDF

- FAO. 1986. Food and fruits-bearing forest species. USA, 3 p. PDF

- Leon, J., Shawm PE 1990. Spondias, the red mombrin and fruits. 136. In: Nag S., et al. (eds.). Fruits and tropical and subtropical origin. Florida Science Sources, Lake Slfred: Florida. PDF

- Mercado-Montiel VS, Carett-Velásquez GJ 2016. Characterization of the bromatological, physical-chemical properties and antioxidant capacity of the pulp obtained from the jobo (Spondias mombin L.) from two areas of the department of Córdoba, Montería, Colombia. Thesis. Food engineering. University of Cordoba, Colombia. PDF

- Navarro-Monterroza F. 2003. General revision of the botanical and productive aspects of Spondias mombin (Jobo). Thesis. Faculty of agricultural sciences. University of Sucre. Sincelejo, Colombia. PDF

- Pérez-Portero Y., Rivero-Gonz{alez R., Suárez-López F., González-Pérez M., Hung-Guzmán B. 2013. Physical-chemical characterization of extracts from Spondias mombin L. (Anacardiaceae). Cuban Journal of Chemistry, Vol. XXV (2), May-August. University of the East, Santiago de Cuba. PDF

- Pérez-Portero Y., Suárez-López F., Camacho-Pozo M., Hung-Guzmán B., García-Garrido M. 2012. Evaluation of the antimicrobial activity of Spondias mombin L. Fabronatura 2012. Third International Congress on Pharmacology of Natural Products. PDF

- Poveda C. 2014. Determination of the influence of production areas on the content of bioactive compounds and the antioxidant capacity of five Andean fruits. Thesis. Chemical engineering. Faculty of Food Sciences and Engineering. University of Ambato, Ecuador. PDF

- Sarmiento GE 1986. Spondias mombin L. 33-34, in: Fruits in Colombia. Bogotá: Colombian Cultural Edition. PDF

- Tiburski J, Rosenthal A, Deliza R, De Oliveira R, Pacheco L. 2011. Nutritional properties of yellow mombin ( Spondias mombin L.) pulp. Food Research International, 44, 2326-2331. Source

- Amazon Cooperation Treaty (TCA). 1999. Promising Fruit Trees and Vegetables from the Amazon. Lima: TCA. Publisher: H. Villachica. Source

Dr. Rafael Cartay is a Venezuelan economist, historian, and writer best known for his extensive work in gastronomy, and has received the National Nutrition Award, Gourmand World Cookbook Award, Best Kitchen Dictionary, and The Great Gold Fork. He began his research on the Amazon in 2014 and lived in Iquitos during 2015, where he wrote The Peruvian Amazon Table (2016), the Dictionary of Food and Cuisine of the Amazon Basin (2020), and the online portal delAmazonas.com, of which he is co-founder and main writer. Books by Rafael Cartay can be found on Amazon.com

This post is also available in:

![]() Español (Spanish)

Español (Spanish)