Biography of a soldier in charge of installing telegraph lines in the Brazilian Amazon. Relationship with Theodore Roosevelt and the Duda River.

If you understand anything about the enormous difficulties a person must face to make his way through the tangled, dark jungle that is life, let me tell you about the beginnings of Cándido Rondón (1865-1958).

To do so, I cannot find more precise words than those of Dante, in the first canto of the Inferno of The Divine Comedy:

“Ah! How painful it would be for me to say how wild, rough and thick this jungle was, the memory of which renews my dread, a dread so great that death is not so great. But before I speak of the good I found there, I will reveal the other things I have seen.”

The roots of Cándido Rondón

Rondón was a caboclo, a kind of caste of denaturalized Indians and mestizos with a strong indigenous influence.

From his birth, things did not go well for him: he was fatherless before he was born, as his father died in 1864, a few months before his birth.

Then his mother died when he was only two years old. He was raised, then, by his paternal uncle Manuel in the midst of great family economic difficulties.

As a teenager, Cándido had no choice but to enter the military, where young men from poor families were attracted. The army offered a modest monthly allowance, with which he could support his family.

A candid telegrapher

The passage of time found him as a soldier busy planting wooden poles to lay telegraph lines in Mato Grosso, as well as in a poor and forgotten region that many years later would be named after him in his honor: the state of Rondônia, located in the northern part of Brazil, on the Brazilian Amazon.

But he did not know that at the time, and he was only concerned, almost obsessively, with making possible the laying of the telegraph line and seeing that it was painstakingly erected from Cuiabá, the capital of Mato Grosso, to the different localities of the vast state.

At that time, the advance of progress was the telegraph, which had arrived in Brazil in 1852. While Candido was growing up and becoming a man, between 1866 and 1886, some 11,000 km of telegraph lines were erected in a good part of Brazil, but the Amazon had yet to be covered.

Amazonian prowess

From that date on, Rondón was involved in every kilometer of telegraph line laid in Amazonian territory. A key and vital activity in the extensive Amazon region where communication, very slow, was done by navigating the rivers.

Brazil wanted to exploit the Amazon at any cost and with urgency, to penetrate it and take possession of its enormous natural wealth, to pacify the Amazonian peoples and hostile tribes that hindered the business, and to create a network of roads and telegraphic communications in order to extend its economic frontier with the exploitation of coffee, cocoa and extract harvesting products such as rubber, the chestnut or Brazil nut, and the guaraná, and to expand livestock, forestry and mining activities to the farthest reaches of the Amazon.

To do so, it was necessary to integrate this inhospitable and unknown region with the rest of the country. The occasion had arrived and Rondón was to play a transcendental and strategic role in that process.

On each trip he made into the interior of the Amazon, Rondón laid telegraph lines, built roads, made maps, established contacts with hostile tribes to pacify them, and discovered new rivers and routes in the jungle.

We see him between 1890 and 1895 building the first major telegraph line through the state of Mato Grosso and participating in the construction of the difficult road linking Rio de Janeiro with Cuiabá, capital of the state of Mato Grosso.

The peacemaker

From 1900 to 1906 he was in charge of the telegraphic connection between Mato Grosso and the border territories with Bolivia and Paraguay, and pacifying hardened peoples such as the Bororó, whose members ended up helping him in the difficult task of opening roads and planting posts in the middle of the jungle.

During his lifetime, Rondón directed the laying of nearly 6,000 km of telegraph lines to serve the Brazilian states of Mato Grosso and Amazonas.

During these trips, he discovered rivers such as the Juruena, a tributary of the Tapajós River, in northern Mato Grosso, and came into contact with the Nambikwara ethnic group, famous for its hostility towards whites and mestizos (whom they murdered).

During the expedition, in the face of the indigenous people’s warlike harassment, Rondón ordered his men not to shoot. From there came his motto and his pacifying method based on understanding and friendship:

“Morrer se preciso for, matar nunca” (to die if necessary, to kill never).

Rondón raised poles, explored unknown corners, and built himself.

The discovery of La Duda river

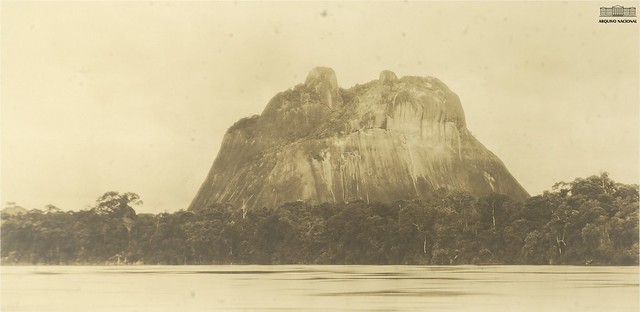

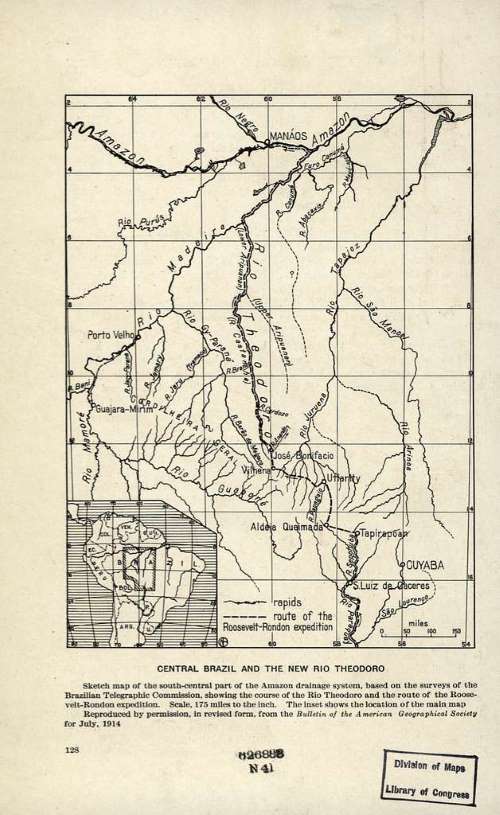

In May 1909 Rondón undertook his longest and most risky expedition. Starting from Tapirapuá, in the north of Mato Grosso, he crossed with his companions the entire northwest until he reached the Madeira River, one of the major tributaries of the Amazon River.

Also available through the Library of Congress website as a raster image.

It was a journey full of difficulties. He and his group were lost, exhausted of provisions, surviving on the resources of the jungle: gathering wild fruits, hunting and fishing, forcibly establishing contact with hostile tribes.

In August, he discovered a large river between the Juruena and the Paraná, which he called La Dúvida River, La Duda River, the location of which was still imprecise and did not appear on maps.

In December 1909, when what was left of the expeditionary group arrived in Rio de Janeiro, they were hailed as heroes, because they were all believed to have died.

Indian Protective Service

In 1910 we find Rondón presiding over the Indian Protection Service (SPI), founded that year.

While in the SPI, he pacified many indigenous groups; among them: the Botocudos, from Minas Gerais, in 1911; the Kaingang from the north of Sao Paulo, in 1912; the Umotina near the Paraguay River; the Parintintim from the Madeira River, and the Gurupi in the border area between Pará and Maranhao, in 1918.

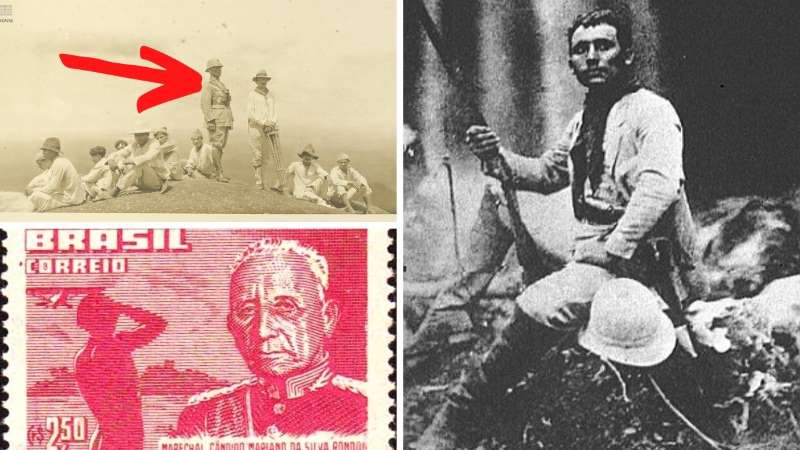

Cándido Rondón and Theodore Roosevelt

The most delicate expedition was the one entrusted to him by the Brazilian government to serve as companion and guide to former U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, who wanted to go on safari in the Amazon, as he had done a decade earlier in Africa. I did not know that visiting the Amazon, with its dangers and diseases, was something that appealing.

Source: Source: scanned from The River of Doubt by Candice Millard 2005.

Rondón chose the exploration of the La Duda River, to navigate its course, map it, and thereby to complete his 1909 task. It was neither an easy trip nor a simple task to ensure the security of a former U.S. president who had just left office.

The group of 19 people, which they called the Roosevelt-Rondón Scientific Commission, left Tapirapuá in January 1914 and reached, after more than a month of hard work, the La Duda River at the end of February of that year.

Lost in the jungle, exhausted of provisions, and physcially exhausted by the effort of walking through the tangled vegetation and navigating the dangerous and treacherous rapids of the river, they had to resort to hunting, fishing, and gathering wild fruits in order to survive.

Everyone got sick, except Rondón, still very strong at 49 years of age, and accustomed as he was to such journeys.

Roosevelt, 56, almost died on the trip, and it is neither literature nor the product of this writer’s fevered imagination.

Sick with malaria, weakened by poor nutrition, with an injured and infected leg, and surrounded by hostile Indians, he was only saved by the energy that emanated from this man accustomed to physical exertion and long working days, not to a soft life of luxury, despite having been rich from birth and having held high positions of political representation, including the presidency of the United States for nine years.

The legacy of a tireless man

Rondón was, for his part, like an oak tree. And he remained so until his death in 1958 at the age of 93.

An example of resistance, he was was active until 1955.

At 80 years of age, he led the pacification and integration of the forgotten regions of central western Brazil, a vast region comprising the territory of the states of Brasília, Goiás, Mato Grosso and Mato Grosso do Sul, which required almost superhuman effort.

When he was about 90 years old, he directed the development of the Xingu Indigenous Park project, which was achieved after his death, in 1961, thanks to the efforts of the Vilas Boas brothers.

In 1953 he accompanied Brazilian anthropologist Darcy Ribeiro in founding and starting up the Indian Museum in Rio de Janeiro.

Darcy was exiled in Venezuela during the military dictatorship and was a professor at the Universidad Central. I can imagine watching him, tireless, with long hair like a young person, speaking at academic forums in Caracas. Darcy was like Rondon, driven by a flame and, as they say, a man of timing, who was always where he needed to be.

On November 15, 1889, Rondón, a 24-year-old stripling, was accompanying Deodoro da Fonseca, the leader who proclaimed Brazil’s independence.

When work began on extending the telegraph service in the Brazilian Amazon, and in particular in the state of Mato Grosso, under Major Antonio Gómes Carneiro, he was also there, as Carlos Benitez Trinidad recounts in a magnificent essay on his life, written in 2017.

Rondón was not a man who did things expecting rewards, but out of a strange vocation of service to the progress of his Amazon.

Tribute

For his participation in the Scientific Commission, which accompanied Roosevelt, he was awarded in 1914 the Medal of the Explorer’s Club of New York, and in 1918 the Centennial Medal of the great explorer David Livingstone, awarded by the American Geographical Society.

In 1955, on his 90th birthday, he was honorarily named Marechal, that is, Marshal of the Army.

A year later, the state of Rondônia was created in his honor.

In 1957 he was nominated by the Explorer’s Club of New York for the Nobel Peace Prize.

Rondón’s name is engraved in gold letters in the book of the Geographical Society of New York.

In the year of his death, 1958, many more tributes were paid to Rondón. A 1,000 cruceiros banknote was issued with his image.

The International Airport of Cuiabá, capital of Mato Grosso, was named Marechal Rondón.

In 2015, Cándido Rondón’s name was inscribed in the Book of Heroes of the Homeland, deposited in the Panteao da Pátria, in Brasília.

But perhaps the most cherished recognition for him may have been the establishment of May 5, the day of his birthday, as Communications Day in Brazil, and he was named the patron saint of the country’s telegraphers.

This post is also available in:

![]() Español (Spanish)

Español (Spanish)