Like the god Janus, of Greek mythology, who symbolized the uncertainty of what is to come, this story presents two faces and two opposing interests: that of the Yanomami and that of the garimpeiros.

The Yanomami, or Yanomomo, live in northern Brazil and southern Venezuela, in a vast territory covering nearly 18 million hectares. They have been there for more than 10,000 years, coming from the first human migrations to the American continent. A long time living in isolation, without contact with the outside world. The large Yanomami ethnic group, which has dwindled to almost 38,000 people. The Yanomami nation comprises three groups: Sanumá, Yanomam and Yanam, who speak different dialects but understand each other. Although not all is harmony between them.

Its long history was turned upside down in the 1940s, when the first settler incursions into the region began. Years later, in the 1970s, the military government of Brazil ordered manu militari, by force, the construction of a large dam that displaced many Yanomami communities, and brought them into contact with workers from urban areas, who were part of the labor crews working on the dam. At that time, many indigenous people died from diseases for which they had no antibodies. It was the time of “lead”, the most repressive period of the military dictatorship of that time, between 1968 and 1974.

The gold diggers

In the 1980s, Yanomami territory was invaded by some 40,000 illegal miners, called garimpeiros in Portuguese. In just seven years, the indigenous population was reduced by 20%. In 1992, the international protest led by several NGOs and the strong resistance of the Yanomami people, led by the indigenous Davi Kopenawa Yanomami, led to the expulsion of the miners. But a year later they were there again. The garimpeiros were apparently returning in peace. They left food and some trinkets for the indigenous people of Hoximú. Once they had gained the trust of the villagers, they killed more than forty Yanomami, adults and children, including a baby. Some were beheaded and even dismembered. The survivors of the Hoximú massacre recounted the horrible tragedy they lived through. And justice was demanded. Of the five murderers, only two were arrested and convicted. Three are still at large.

Other governments, such as that of Itamar Franco, have issued indigenous protection decrees, which later became a death letter during the government of Jair Bolsonaro, who boasted of proclaiming that the Brazilian Amazon is a sovereign matter, in which no other country should intervene.

Bart Wursten Garimpeiros on the move. Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

On January 20, 2023, the government of Lula da Silva, with the committed participation of the long-time indigenous rights fighter Marina Silva, now a minister, issued a decree expelling about 20,000 garimpeiros from the territory assigned to the Yanomami. These illegal miners will surely move to other Amazonian territories, such as Venezuela, Guyana or French Guiana, where justice is more lax.

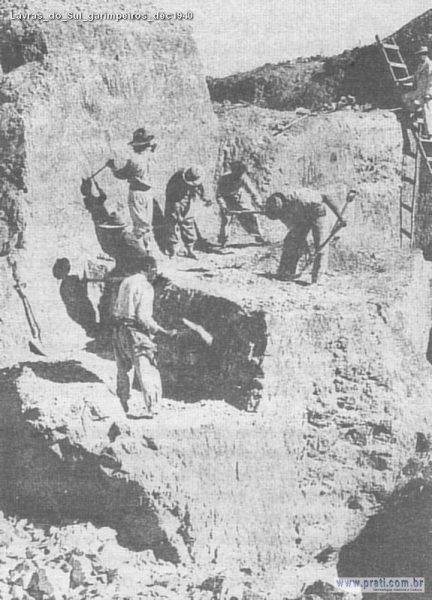

Who are the garimpeiros?

Garimpeiros, as they are known in Portuguese, are illegal miners who search for gold and precious minerals in the Amazon rainforest. They deforest and destroy nature in their quests. What they leave are sores, rather than scars, on the land they ravage. They use mercury for ore treatment, and in other cases cyanide, substances that pollute watercourses in a vast region where rivers are closely interconnected.

A garimpeiro is a poor person who desperately seeks to change his or her destiny by finding a vein or vein of gold, or diamond stones in a stream bed. Poor, desperate, bestialized, insensitive people for whom indigenous people are worth little. In their destructive work they use heavy and powerful machines that must be transported in a very visible way through the jungle roads. Their devastating work is easily detectable by satellite signals. And it is known, and sometimes it is denounced, but the authority, bribed, remains silent and approves. In short, the victims are a vast jungle, mute and with almost no mourners, and indigenous groups considered as savages, less than people, as if we were in the colony or in the cursed times of the cruel rubber barons.

Behind the garimpeiros, lurking in the background, are the profiteers: national and multinational companies that buy precious stones regardless of the blood they cost and the pain inflicted on the native populations. This is the case in Africa, Asia and the Americas. Sometimes one wonders how many human lives a few grams of gold have cost, how much pain is contained in a diamond that sparkles in a jewel.

Dr. Rafael Cartay is a Venezuelan economist, historian, and writer best known for his extensive work in gastronomy, and has received the National Nutrition Award, Gourmand World Cookbook Award, Best Kitchen Dictionary, and The Great Gold Fork. He began his research on the Amazon in 2014 and lived in Iquitos during 2015, where he wrote The Peruvian Amazon Table (2016), the Dictionary of Food and Cuisine of the Amazon Basin (2020), and the online portal delAmazonas.com, of which he is co-founder and main writer. Books by Rafael Cartay can be found on Amazon.com

This post is also available in:

![]() Español (Spanish)

Español (Spanish)