This calendar of Amazonian harvest and gathering festivals will let you know when to gather fruits, fish or hunt in harmony with nature

This article on the harvest festival is a summary of these last five years in which I have been carefully examining the socio-anthropological, ethnobotanical, and ethnozoological literature related to the countries of the Amazon basin. I have learned to love the work of two great scholars, both now deceased, to whom I owe an immense intellectual debt in my modest knowledge of the Amazon.

One is the Peruvian educator, writer, and environmentalist Antonio Brack Egg (1940-2014).

The other is the Colombian ethnobotanist Víctor Manuel Patiño (1912-2001), who never ceased to amaze me by the depth of his work and the admirable perseverance of his long effort.

VM Patiño, in his latest book, History and Dispersion of Native Fruit Trees in the Neotropics (Cali: CIAT, 2000), published at the age of 89, points out that the time when wild fruit trees bear fruit, initiating the harvest period, goes unnoticed by many people, but not by collectors who depend on those fruits for their survival: their food and economy.

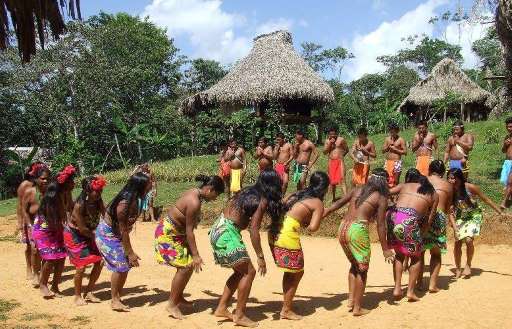

In the Amazon, the indigenous people of the native communities mobilize at each harvest time, attracted by the abundance, and they celebrate the plethora of fruits with a party.

Harvest festivals around the world

Harvest festivals happen not only in the Amazon, but also in rural areas almost everywhere on the planet.

It is the harvest festival of the prickly pear (Opuntia ficus) in North America, in the middle of autumn.

Or the dance of the carob tree harvest (Prosopis alba, P. nigra) in the Chaco, a region between Bolivia, Paraguay, and Argentina, in which people dance to the rhythm of the pin pin drum and drink aloja or carob chicha.

Or the harvest festival in La Rioja Alavesa, in Logroño, between October and November, in which bunches of grapes (Vitis vinifera) are trodden in vats by barefoot men, as required by tradition.

Or the Inti Raymi festival in the Andean Sierra, when the producers thank Paccha Mama for the harvest of their products at the end of an Andean agricultural cycle in June during the summer solstice.

Or the visits by people at the beginning of spring, even with the snowy landscape of Quebec, Canada, to the “cabanes á sucre” to collect honey d’érable, or maple syrup (Acer saccharum).

They are all festivals celebrating and giving thanks for the fertility of the land and the abundant harvest. Their origin dates back to the thesmophoria in ancient Greece, which were religious festivals dedicated to Demeter, the goddess of harvest and fertility, and her daughter Persephone, to thank the deity for a good harvest. The Greek playwright Aristophanes wrote a play The Thesmophoria, dedicated to Demeter, performed in 411 BC.

The harvest of wild fruits in the Amazon

At harvest time, the Amazonian indigenous people would leave for a time the reductions or Indian towns where they were concentrated, and go on a pilgrimage to collect the fruits and celebrate the abundance.

The missionaries complained about their inability to retain them in their missionary work, which was a great setback for them. These recurring and seasonal pilgrimages were called “mitas” in Quechua, a term that means shifts.

Patiño (2000) mentions that Father Lucas de La Cueva wrote, in Jébero, on October 9, 1643, about the difficulty he had with the half of the turtles that the indigenous people took on their own, and that it was like “opposing the most furious currents…”.

Father Lucas was referring to the spawning season of the charapa arrau turtles (Podocnemis expansa) or taricayas or terecayas (P. unifilis ), which nest collectively from March to April; the indigenous people moved to the beaches of certain rivers to seize their eggs in the summer, at the time of the descent of the Amazonian waters (Castro-Casal et al 2013).

If it wasn’t to collect turtles, it was to collect drupes of aguaje, morete or moriche (Mauritia flexuosa), or pijuayo, chonta or chontaduro (Bactris gasipaes). But there was always a reason for the pilgrimage; it was the harvest festival, when the jungle rejoiced and the soul was animated.

The most outstanding festivities in the Amazon are those for the harvest of palm trees, especially Bactris gasipaes or Mauritia flexuosa, which have numerous uses and are fundamental in the daily life of the native indigenous communities.

The harvest seasons of the main Amazonian harvested fruits became milestones in the annual calendar, as also occurred with the harvest of the chestnut or Pará nut (Bertholletia excelsa).

The importance of harvest festivals, writes Patiño (2000: 30), is that they are associated with food regimens.

The festivities were also associated with the consumption of beverages derived from products rich in carbohydrates, ripe, and fermented, thanks to the sugars they contained, as was the case with chicha or masato, made from cassava, corn, or sweet potato, or from palm drupes that abounded in large concentrations.

The plants were almost always the result of long processes of domestication and selection by the indigenous people to obtain cultivars at their convenience.

Festivals of the Ecuadorian Amazon

Over time, and as a result of the commodification processes, the native communities began to establish fairs or festivals of harvested plant products to attract national and foreign visitors, and boost their depressed economies.

Chonta party

In the Ecuadorian Amazon, the Kichwa, Shuar, Achuar, and Cofan ethnic groups celebrate, for example, the festival of the chonta or chontaduro between April and May, which they call uwi. The party includes rituals, dances, songs, and meals.

The Shuar people have celebrated since April 21, 1972 the festival of the chonta or harvest of the chontaduro (Uwi ijiampramu), a drupe of the chonta palm (Bactris gasipaes).

The harvest begins in February and lasts until April. The ritual is presided over by a wise old man, Unt wéa, who directs the party in which the attendees dance and drink the fermented chonta chicha until they get drunk, accompanied by the repetitive sound of a drum in the background.

In the Amazon basin, the native indigenous communities organize their calendar and their activities according to the rising and emptying of the rivers.

In this region the rivers are considered sacred and the element of water is like a supreme priest who imposes his law in the Amazon. These are activities governed by tradition and guided by indicators related to indigenous ancestral knowledge — a knowledge that is transmitted from generation to generation, and that the great French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss called a “science of the concrete,” a knowledge “constructed through a mental activity that relates phenomena in many cases from their sensible qualities, and interpreting in many other cases the relationships between these elements of the natural environment with society” (Lévi-Strauss 1975: 39-40).

In the Peruvian Amazon

A single example will suffice to illustrate the point. For the Asháninka, an indigenous ethnic group that lives in the alluvial plains of the Ucayali river valleys in the Peruvian Amazon, the flowering of the shismáshiri tree, a kind of Cassia, heralds the beginning of the season of emptying of the waters and the fattening time of the animals of the forest (Rojas-Zalezzi 1994: 149-150).

For the Asháninka, the seasonal passing of time constitutes an annual calendar of activities established based on astronomical and hydrological criteria.

In addition, floristic and faunal criteria are used. These indicators are necessary to organize their horticultural activities (in their chagra, or local farming community), as well as hunting, fishing and gathering.

For the Ashaninka, the year is divided into two major seasons: that of intense rains and rising rivers from December to mid-March, and the season of empty rivers, from March to November (Rojas-Zalezzi 1992). : 175-176).

The researcher Gabel Sotil García, a resident in Iquitos, capital of the Loreto region of Peru, in his book “Omagua. I sing to the kingdom of waters and trees” (2007), traces the changes that Amazonian nature undergoes, month by month. He guides us in our story. Let’s read it.

Harvest calendar in the Amazon

January

In January the waters of the rivers overflow. The tangarine blooms and the huayo ripens.

February

In February the pipes and streams overflow, following the rising of the rivers. The indigenous farms of the lowlands are flooded. The granadilla, the cigar, the sapote, the umarí, the uvilla and the parinari bear fruit. The restingas, or sandbars, become refuges for the collared peccary, the majás, the añuje, the carachupa and the motelo. It rains persistently and the aguaje ends up bearing fruit.

March

In March the waters of the rivers reach their maximum level and farmhouses and crops are flooded. Schools are closed for three months each year due to flooding. The fish fatten even outside the rivers, between the litter and the flooded roots. The animals of the mountain migrate, seeking refuge in the highest restingas, or sandbars.

April

In April the rain continues and everything looks like the days of the deluge. Dawns are musty, cold and humid. It is the month in which guaba, ubos and camu camu are harvested.

May

In May the rains continue, but they appease their fury, and the rivers slowly begin their decline. It is the time to harvest the fruits of the rose apple, the guaba, the caimito, the taperiba, the casho, the arazá, the ungurahui, the yarina, the cocona, the aguaje, and the tansharina. The animals of the mountain return to their old haunts.

June

In June the waters begin to recede and the activity of people and animals in the lowlands is reborn. Sandy beaches and mudflats appear. The time for sowing begins on the wide beaches of the rivers as they recede. Everywhere you can see the crops of Chiclayo, beans, corn, cassava, rice, tomato, watermelon, melon, pumpkin. The fish colonize the river again, leaving behind the tahuampas (or flooded pools), the oxbow lakes and the ravines, forming agitated schools. The fishing season begins.

It is also the time of the dazzling festival of San Juan, which takes over the urban Amazon with its strident music in public and private places. The juane dish is served and eaten in its various forms, and eroticism is charged to the brim. The indigenous communities, absent from this revelry, begin their sowing rituals with songs and dances. It is the time of the surprising and brief cold, when the cold winds that come from Antarctica penetrate for a few days among the trees of the thick jungle.

July

In July the riverbeds are narrowed, the lakes are reduced, and the fish continue to leave the flood pools and the ravines in search of the rivers. Taricayas and cupisos spawn on the beaches of some rivers. The indigenous people know that summer has finally settled in because the turtles lay their eggs, hidden in the sand on the beach. First the land turtles spawned in June and now, in July, it is the turn of the aquatic turtles. The sun is already strong and the heat is pressing.

August

In August the sky is intensely blue, the emptiness is full, and the torpor is almost unbearable. The harvest of melons, watermelons, pineapples, corn and chiclayos continues. The hunter, or mitayero, is on the lookout for the animals of the mountain, which distrust everything. The taricaya and cupiso eggs have already hatched.

September

In September the charapa turtle spawns on the beach. The islands are surrounded by extensive sandbanks. The harvest of pineapples, melons, and watermelons continues. It rains little and the heat intensifies. It is the month of harvests and large schools of fish. Fishing abounds. Fish migrate, upstream or downstream, and return to the lakes and flood pools.

October

In October the last harvests of melons, watermelons, chiclayos, camitos, guabas, yucca, and rice are harvested. The charapa pups, or charitos, begin with difficulty and almost desperation to try to reach the waters of the river to avoid the predators that lie in wait for them. The fish, which have laid their eggs in the gramlotes and leaf litter to ensure their reproduction, are preparing to return to their domains, awaiting the signs of nature. It rains in the Sierra and the rivers begin to swell again, and the waters begin to rise. They have already spawned the gamitana, the boquichico, and the tucunaré. The fish get excited when they return to their places of origin. Another life cycle has been completed in the deep Amazon.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Castro-Casal, A., Merchán-Fornellino M,…et al. 2013. Historical and current use of charapa (Podocnemis expansa) and terecaya (P. unifilis) turtles from Orinoquia and Amazonia. BIOTA COLOMBIANA, Vol. 14 (1), 45-64. PDF

- Levi-Strauss C. 1975. The Wild Thought. Mexico: FCE. PDF

- Patino VM (2000). History and dispersal of native fruit trees in the neotropics. Cali: CIAT. Source

- Rojas-Zalezzi E. 1994. The Asháninka. A town behind the forest . Lime. PUCP. Source

- Rojas-Zalezzi E. 1992. About knowing when to do: the Asháninka calendar and the annual cycle of activities. Anthropologica, No. 10, December. Source

- Sotil Garcia GD 2007. Omagua . I sing to the kingdom of waters and trees. Iquitos: GD Sotil Garcia. Source

Dr. Rafael Cartay is a Venezuelan economist, historian, and writer best known for his extensive work in gastronomy, and has received the National Nutrition Award, Gourmand World Cookbook Award, Best Kitchen Dictionary, and The Great Gold Fork. He began his research on the Amazon in 2014 and lived in Iquitos during 2015, where he wrote The Peruvian Amazon Table (2016), the Dictionary of Food and Cuisine of the Amazon Basin (2020), and the online portal delAmazonas.com, of which he is co-founder and main writer. Books by Rafael Cartay can be found on Amazon.com

This post is also available in:

![]() Español (Spanish)

Español (Spanish)