One of the most extraordinary books written on the ethnology of indigenous societies in the 20th century is Tristes Trópicos (The Sadness of the Tropics), (1955), by Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908-2009).

It is a difficult book to classify, if one examines it as a unit.

But it is, without a doubt, a masterful work, composed of: a clearly autobiographical section, as if it were a travel book by a Frenchman to America in the period 1935-1942; and another section where he briefly mentions his academic training and the consolidation of his profession as an ethnologist.

He does not, however, recount any events of his family life – he was married to the French anthropologist and philosopher Dina Dreifus – nor of his experience as a teacher in São Paulo, nor of his intellectual enrichment during his years at the New School for Social Research in New York.

Part 1: The journey

The first part of his book, in which the author narrates his eventful departure from France on two occasions (1935, to Sao Paulo, and in the 1940s, to New York), can be considered a travel book, because of its detailed descriptions of the landscape, the changes in the climate, the cities visited and the behaviors of fellow travelers.

Copyright Holder: National Archives

Type of material: negative (black / white)

These sensations are masterfully communicated to the reader, who feels, almost on the surface, how the climate changes, the heat settles in, and the tropics approach.

These were new and important sensations for an educated European who had lived in very different environments.

Part 2: Living in the Amazon

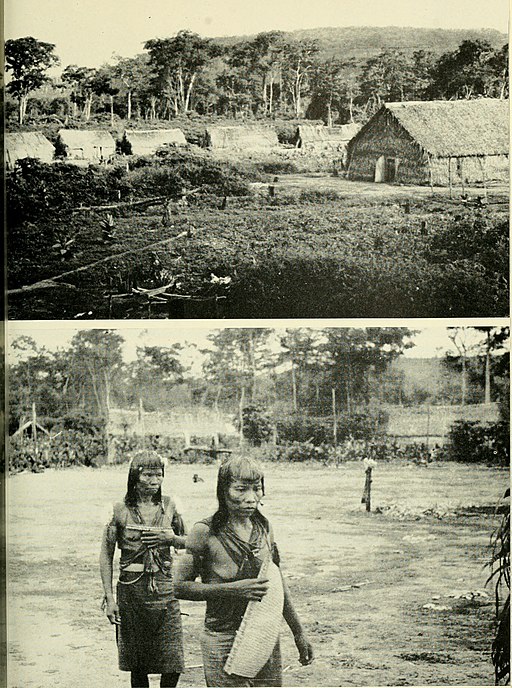

In the other part, the major part of the book, Lévi-Strauss recounts his ethnological work with Brazilian Amazonian indigenous societies.

He then moves away from the travel book and dives right into ethnography.

At the time it was said that the book was too well written, to the point that many saw it more as a novel than as a philosophical reflection on the ethnologist’s profession. Or, as a sort of autobiography of a young French graduate in philosophy and anthropology who traveled to Brazil, specifically to the city of Sao Paulo, capital of the state of Sao Paulo, as part of a cultural cooperation mission of the French government, and who ended up teaching sociology at the University of Sao Paulo from 1935, and doing ethnographic work for almost three years on various Amazonian indigenous groups inhabiting the Amazon region of northern Brazil, especially in the states of Amazonas, Rondônia (which did not yet exist) and Mato Grosso.

At that time, he studied the Bororo, the Caduveo, the Kaingang and the Nambikwara, relatively unknown ethnic groups and considered to be very warlike.

Ephemeral human constructions

There is, in addition, a key element of the book Tristes Trópicos cited in the preface.

This is a short verse by the Roman philosopher and poet Lucretius (94 B.C.- 55 B.C.), taken from his poem Rerum Natura ( III, 960-969, Madrid, 1968, in the translation of Abbé Marchena, p. 165): Nec minus ergo ante hace quam tu cecidere, cadentque, which translates, according to Marchena:

“All things that came before you are dead, just as those that will come after you will succumb.”

Verse by Lucretius (94 B.C.- 55 B.C.) in his poem Rerum Natura

This poem expresses Lucretius’ idea of change and his defense of the philosophical ideas of the Greek Epicurus and the atomistic physics of the Greek philosophers Leucippus and Democritus (his disciple), the founders of atomism, or the doctrine that postulated that atoms are infinite particles, indivisible, of varied forms and always in motion.

Its constitutive and original principle is the arche, which is part of the multiplicity of beings in nature. With the choice of this preface, says Christopher Johnson (in New Left Review, 79. 2013), the philosophical attitude of Lévi-Strauss is expressed and the idea behind his concept of the evolution of history: that the nature of human constructions is ephemeral and we only witness a perpetual crystallization and dissolution of civilizations.

Progress is, therefore, nothing more than a mirage.

But…

Who is Lévi-Strauss and what does he represent for the social sciences?

Lévi-Strauss was one of the best known social scientists in the Western world during the second half of the twentieth century, during which his intellectual life was spent. He is the custodian of the tradition of the great social scientists of the 19th century: Durkheim, Freud, Jung, Marx, Dewey, Weber, Keynes, Wallace, Humboldt, Darwin.

Graduated in philosophy, but with an early anthropological vocation (studies he did on his own), which he began to practice before age thirty in the Brazilian Amazon, he ended up being considered as the father of social structuralism and the renovator of modern ethnology.

By his own admission: in ethnology,

“I am completely self-taught: I never attended lessons in this discipline, I didn’t even know of its existence. I had my first revelation for unspeakable reasons: yearning for escape, desire to travel, etc.”

After an academic stay of several years in Brazil, based in Sao Paulo, he returned to Paris in 1939. World War II had begun and he was mobilized as a combatant.

As best he could, he escaped to Martinique, a French colonial dependency in the Caribbean, and from there traveled, with great difficulty and fear, to New York, carrying a trunk full of files and data from his Brazilian ethnographic works. Let’s hear it:

“Throughout my heritage I carried a trunk with the documents of my expeditions: linguistic and technological files, a route diary, notes taken in the field, maps, plans and photographic negatives: thousands of sheets, files and clichés .”

Lévi-Strauss (Tristes Trópicos, 37).

He traveled, jealously guarding his trunk, to join the New School for Social Research in New York, which had become the center of the intellectual avant-garde of the Western world in social sciences and art, replacing Paris and London.

There, he met and was influenced by the Russian linguist Román Jakobson, who had developed structuralism in linguistics, and the Russian phonologist Nicolai Sergeivich Trubetzkoy, father of phonology and who popularized the concept of the phoneme. These were complemented by readings of Ferdinand de Saussure, which led Lévi-Strauss to the field of structuralism, which he applied with great success in the field of social anthropology.

Lévi-Strauss the anthropologist-ethnologist was formed during his stay in Brazil. Lévi-Strauss the structuralist was formed at his Niuyorcan residence.

In 1947 he returned to Paris to present a dissertation on the family and social life of the NAMBIKWARA Indians, and then to obtain his doctorate in 1949 with his thesis on the elementary structures of kinship.

These works earned him his academic consecration. Lévi-Strauss showed that kinship structures constituted components of a single system based on the prohibition of incest.

Thus, the social structure moved from natural consanguinity to a cultural alliance based on marriage and understood as a cultural exchange.

Ethnology, anthropology and structuralism…

Lévi-Strauss conducted the first structural research on this topic, which later became a research model for ethnographers.

It says :

“More than a journey, exploration is scrutinizing; a fleeting scene, a corner of the landscape, or a reflection caught in flight, is the only thing that allows us to understand and interpret horizons that would otherwise be sterile “.

(Tristes Trópicos, 52)

Lévi-Strauss established with his texts that the supposedly backward “primitive” thought employs the same structuring rules as the most modern of scientific thinkers.

No less important are his studies on myths in South American cultures, which gave rise to the “Mythological” series, in four volumes:

- De lo crudo y lo cocido – Of the Raw and the Cooked (1964),

- De la miel a las cenizas – From Honey to Ashes (1967),

- El origen de las maneras de mesa – The Origin of Table Manners (1968), and

- El hombre desnudo – The Naked Man (1971)

In that series, he attempted to reconstruct our thinking, comparing thousands of indigenous myths, and which led him to create the “mythemes,” which are expressed through oppositions (high/low, raw/cooked, dry/wet, hot/cold, etc.), that is, through the symbolic oppositions existing between nature and culture, which have been so influential among those of us who are dedicated to the study of the socioanthropology of food and the semiotics of food. And this was then analyzed by Jacques Derrida, revealing the traps of the structures of binary oppositions, of its center, and how the complementary “Other” is marginalized, dominated or despised.

His fame as an intellectual came with the writing of Tristes Trópicos, in 1955, twenty years after his research experience in the Brazilian Amazon.

It is, therefore, a book resulting from a reflection of two decades, time in which Lévi-Strauss had changed a lot, deepening his theoretical contributions.

That young wine had matured to form a grand cru of social science thought.

Of that young author, only the shell of his first experiences in the field remained, even though one might think lightly that it was everything. The pulp or the core of Levistraussist thought was slowly forming in his travels to Asia, in his countless lectures, in his teaching sessions at the Université de Paris-Pantheon-Sorbonne and at the College de France, and in his numerous publications.

Lévi-Strauss tells in Tristes Trópicos that he knew that a great researcher would give a lecture at the Sorbonne, and that he, however, did not attend, perhaps because of the lack of humility of his self-sufficiency in the subject.

The Amazon as a burnt perfume in Lévi-Strauss’ last years

Many years later, studying for a doctorate at the same university, Sorbonne, I attended out of curiosity (and motivated by ignorance), several courses of Monsieur le Professeur Lévi-Strauss. I attended without any obligation, only fascinated by his overwhelming intellectual personality and his greatness.

The Amazonian experience had left a deep mark on his theoretical discourse, although one could already sense that he was a far cry from the young professor in his twenties, bearded and with a camera on his shoulder, as he appears in the photos of his arrival in Brazil at the time.

As a novice researcher, he gave his first university classes (he had already given them in a high school in France) at the University of Sao Paulo, and ventured into the Amazon jungle, with so many difficulties of transportation and discomfort in the overnight stays and meals, and suffering with pests and diseases, the constant dangers of the jungle, and the fears instilled by the behavior of indigenous people who he viewed with suspicion and who had reactions that he did not understand very well at the time.

He had seen and lived so much that, near his death, almost a centenarian (he ended up living 101 years), he wrote:

We live in a world where I no longer belong. The one I knew and loved had 1.5 billion inhabitants. Today we have more than 6 billion. This world is no longer mine.

Somewhere, Lévi-Strauss wrote:

“Never again, anywhere, will I ever feel at home again.”

By this time, the Amazon that he had known and studied, and that was related to his academic beginnings and his dreamy youth, had become a ruinous present, disfigured, a penetrated reality, largely deforested, fragmented by roads and dams, corrupted by local politicians, and had been placed at the service of the large multinationals and the mafias that extracted minerals from its entrails.

The journey to the “origins” to recover nature and the Rousseaunian “primitivism” of his beloved master and brother Rousseau, and to assert his word questioning the myth of “progress,” had already been muted by populism and the promises of modernity. That world was no longer his.

“Today I think of Brazil like a burnt perfume.”

(Tristes Trópicos, 51).

In 1935, when he went into the Amazon jungle, in the arduous and little traveled paths of the jungle, there existed indigenous human societies full of vigor that, later, with the arrival of civilizational progress, became, for Lévi-Strauss, simple masks, sad tropics.

The biological and cultural diversity of the Amazon regions was altered and sadly brought to a condition of great vulnerability, threatened with extinction.

In El hombre desnudo (1971, Mexico: FCE, 577), Lévi-Strauss speaks of these accelerated and profound changes:

“The human condition underwent a greater change between the eighteenth century and the twentieth century than between the Neolithic period and modern times.”

Dr. Rafael Cartay is a Venezuelan economist, historian, and writer best known for his extensive work in gastronomy, and has received the National Nutrition Award, Gourmand World Cookbook Award, Best Kitchen Dictionary, and The Great Gold Fork. He began his research on the Amazon in 2014 and lived in Iquitos during 2015, where he wrote The Peruvian Amazon Table (2016), the Dictionary of Food and Cuisine of the Amazon Basin (2020), and the online portal delAmazonas.com, of which he is co-founder and main writer. Books by Rafael Cartay can be found on Amazon.com

Related Posts

This post is also available in:

![]() Español (Spanish)

Español (Spanish)