The most famous of the Amazonian adventurers, and the most controversial among them, was the English explorer and archaeologist Percy Harrison Fawcett (1867-1025).

His adventurous spirit runs in his family.

His father was a member of the Royal Geographical Society, London. Edward, his older brother, was a prominent mountaineer, a writer of adventure novels and a fan of oriental occultism.

Percy H. himself was a military man who served in the Royal Artillery Corps in Ceylon, and later acted as an agent for the British service in North Africa.

He rubbed shoulders in London with renowned novelists such as Arthur Conan Doyle and H.R. Haggard.

Dr. Rafael Cartay is a Venezuelan economist, historian, and writer best known for his extensive work in gastronomy, and has received the National Nutrition Award, Gourmand World Cookbook Award, Best Kitchen Dictionary, and The Great Gold Fork. He began his research on the Amazon in 2014 and lived in Iquitos during 2015, where he wrote The Peruvian Amazon Table (2016), the Dictionary of Food and Cuisine of the Amazon Basin (2020), and the online portal delAmazonas.com, of which he is co-founder and main writer. Books by Rafael Cartay can be found on Amazon.com

Amazon Expeditions

Fawcett’s first expedition to South America took place in 1906, when he was part of a commission charged with mapping (Fawcett was also a topographer) the jungle border separating Brazil and Bolivia in the British mediation of the border dispute.

From that first incursion into the Amazon, some revelations were left behind that were labeled as exaggerations.

One of them was the sighting of a 19 meter long anaconda, and some other little known jungle animals: such as a black wild dog, probably a jaguar, or a giant spider.

During the period from 1906 to 1925 he made a total of seven expeditions.

In 1910 he made an important expedition searching for the source of the Guaparé and Heat rivers, on the border between Peru and Bolivia.

Upon his return to England, he joined the army to fight in World War I (1914-1918).

At the end of the war he returned to Brazil to study the fauna and flora. At that time he became obsessed with the existence of a great city lost in the Brazilian jungle, in the region of Mato Grosso.

“Z” or “raposo” the mythical lost city of the Amazon.

Fawcett had found an 18th century Portuguese document, “manuscript 512”, which referred to a large city, which he called Z.

In his long searches he found a ruined city, to which he gave the name of Raposo.

In 1925 he returned to Brazil, this time accompanied by his eldest son, Jack, and a friend of his, and went into the jungle, loaded with supplies and measuring instruments.

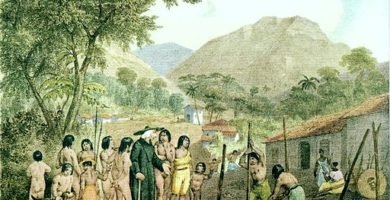

Source: Fundação Biblioteca Nacional [Public domain]

Strange disappearance

On April 20, 1925, they left Cuiabá. His last written communication was a letter to his wife, dated May 29, informing her that he was near the Xingu River, and that they were entering unknown territory, near the Kalapalo tribe, the last to see them.

A great silence followed, which was exploited by the English press to build up a great mystery, prompting a series of 13 expeditions, in which about 100 people died, that found some traces of Fawcett and his companions: a nameplate in 1927, the explorer’s compass in 1933.

Since then, little has been said about the lost cities of the Amazon.

The lost trail of Fawcett’s last expedition

In 1960, Danish explorer Arne Falk-Ronne traveled to Mato Grosso. In his travel book, published in 1991, he noted that Fawcett was probably killed by the Kalapalo Indians for not bringing them gifts, which was considered a breach of protocol.

In 2004, the British newspaper The Observer noted that Misha Williams, a TV director, noted in a program that Fawcett did not want to return to Britain and founded a theosophical commune.

In 2005, 80 years after Fawcett’s disappearance, David Grann of The New Yorker visited the Kalapalos to shed light on the mystery, and concluded that Fawcett had most likely been murdered by fierce indigenous people of the region.

Source: Villas Bôas family archives.

Other lost cities of the Amazon

The Scottish novelist Arthur Conan Doyle created the character of Professor George E. Challenger, based on the notes of Fawcett’s 1906 trip for his novel The Lost World, published in 1912 and set in the Amazon, which initiated the literary genre of dinoasaurs.

Later, the Indiana Jones series was inspired in part by Fawcett’s adventurous life, as was James Gray’s book and the movie it inspired: “Z, the Lost City,” filmed in 2017.

The lost cities of the Amazon continued to arouse the curiosity of adventurers and scientists.

The Great Amazonian Civilization Hypothesis

In 1989 a publication by the American Anne Roosevelt appeared, in which she argued that in the region of Terra Pintada, in Santorém, in the Brazilian state of Pará, a great Amazonian civilization arose whose inhabitants developed early ceramics and applied the “terra petra” (black earth) fertilization method.

According to W.M. Denevan (1996) this black soil was transported from the lowlands to the highlands to compensate for the nutrient poverty of these soils.

This system corresponded to a management model of anthropogenic forest areas, with a high concentration of subsistence natural resources, typical of large populations.

In a later publication, Roosevelt (1994) returned to the subject, suggesting that the occupation of the Amazon is about 12,000 years old.

Other archaeologists such as Donald Lathrap, in his book The Upper Amazon (1970), considered that the Amazon was not the “virgin” forest it was thought to be, that it had a long history of environmental management and that it had been home to large populations.

Other indications of the lost city of “Z”.

Subsequently, the American archaeologist Michael Heckenberger (2009) reported the discovery of the remains of an Amazonian civilization called Kuhikugu, near the Xingu River, among the Kuikoro.

The search for the Lost City of Z was then renewed in a book by Gram (2009).

It brought back to the academic table the idea of the complex and great civilizations of the 18th century, with centralized government, great works, black lands of high agricultural productivity and the transformation by Amazonian groups of biodiversity and forest landscapes (Clement et al 2015; Schmidt, et al 2014).

And there is talk of more in more large archaeological complexes in Santarem, on the island of Marajó, in Macapá and in the vicinity of Manaus.

In contrast to the known existence of the small and simple Amazonian indigenous civilizationsThese contradict the accounts of several chroniclers of the XVI and XVII centuries, who referred to very dense populations and large villages, which were decimated by epidemics and the abuses of Portuguese and Spanish conquerors and colonizers.

Bibliography

- Clemens C.R., Denevan W.M., Heckenberger M.J., Braca-Junqueira A., Neves E.G., Texeira W.G., Woods, W.I. (2015). proc. of the Royal Soc. Biological Sciences, Vol. 282, Issue 1812, August .

- Denevan W.M. (1996). A Bluff Model of Riverine Settlement in Prehistoric Amazonia. Annals of theAssociation of American Geographers, 86 (4).

- Grann D. (2009). The Lost City of Z: A Tale of Deadly Obsession in the Amazon. New York: Doubleday.

- Heckenberger H. (2009). Lost cities of the Amazon. Scientific American. Vol. 301 (4), 69-71.

- Lathrap D.W. (2010). The Upper Amazon. Santiago Rivas Panduro (ed.). Lima: Instituto Cultural Runa/ Institute of Andean Research.

- Roosevelt A. (ed.). (1994). Amazon Indians. From Prehistory to the Present. Anthropological Prospection. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press.

- Roosevelt A. (1989). Resource Management in Amazonia Befor the Conquest: Beyond Ethnographic Projection. Resources Management in Amazonia: Indigenous and Folk Strategies, Vol. 7, Advanced in Economic Botany, New York: The New York Botanical Garden.

- Schmidt M.J., Daniel A.R.P., Moraes C.de P., Valle R.B.A., Caromano C.F., Texeira W.G., Barbosa C.A., Fonseca J.A., Magalhaes M.P., Carmo Santo, D.S. Silva, R.D., Guapindaia V.L., Moraes B., Lima H.P., Neves E.G., Heckenberger M.J. (2014). Dark earths and the human built lasndscape in Amazonia: a widespread pattern of anthrosol formation. Journal of Archaelogical Science, Science, Vol. 42, February, 152-165.

Related Posts

January 8, 2020

1. The Conquerors and colonizers of the Amazon Rainforest

January 11, 2020

2 . Missionaries in the Amazon Rainforest (17th century)

January 13, 2020

3. The Utopia of the Earthly Paradise in the Amazon Rainforest

January 16, 2020

4. Great naturalist scientists in the Amazon Rainforest (18th to 19th centuries)

January 19, 2020

5 . The rubber barons between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century.

January 20, 2020

7. The Amazon Rainforest today (XXI Century)

January 8, 2020

History of the Amazon Rainforest Explorers

This post is also available in:

![]() Español (Spanish)

Español (Spanish)