While researching articles and books on the exploitation of the sarrapia (Diphisa punctata), also known as cumaru, cumbaru, tonka bean, camaruna, I came across several pleasant surprises.

The first is that one of the great sarrapia producing areas in the world is the middle Orinoco area, where the fruit has been exploited, and then exported, since the 19th century.

The second is that such exploitation has been closely linked to the Mapoyo indigenous group, which almost no one knows, myself among many, but which constitutes an intangible cultural heritage of humanity declared by UNESCO in 1994.

As a result of my ignorance about this declaration, I searched for information about the Bolivarian ethnic group. The third is that sarrapia has been, like so many other resources in our country (Venezuela), taken advantage of by those close to the regime.

Rómulo Betancourt wrote on March 10, 1937, in the newspaper Ahora, that as of that year the government had decided to declare free the exploitation of the sarrapia, which until then had been the object of monopoly concessions in favor of a private contractor and the dictator’s sons. J.V. Gomez.

The sarrapia collectors had to pay 50 bolivars to the contractor and an additional 50 bolivars to the commercial houses that financed the business.

Joselvazquezm / CC BY-SA

Sarrapia characteristics

The sarrapia(Dipteryx odorata, D. punctata) is a tree up to 30 m tall, with a straight trunk and leafy crown, which grows wild in southern Venezuela, northern Brazil and the jungles of Guyana.

The leaves of the tree are of medium size, 6 to 15 cm long and 3 to 6 cm wide.

The tree grows wild in the Guayana area of Bolivar State, and its fruits, which are drupes, are harvested once they fall to the ground. The tree produces its harvest every two years, around April.

Each tree bears an average of 30 kg of fruit, representing about 6 kg of seed, which fetches high prices in the market, but is not in great demand now, although it was during the nineteenth and mid-twentieth centuries.

Monster46 / CC BY-SA

The fruit is an ovoid (oval), drupaceous legume (a fruit with a seed inside, wrapped in a hard woody coating), indehiscent (does not open to disperse its seed).

The shell is hard when dry, dark brown in color. The seed it contains is dried in the sun, then macerated in alcohol, usually rum, and then dried again.

It is stored in an airtight container and placed in a cool, shaded place, which guarantees its conservation for at least two years.

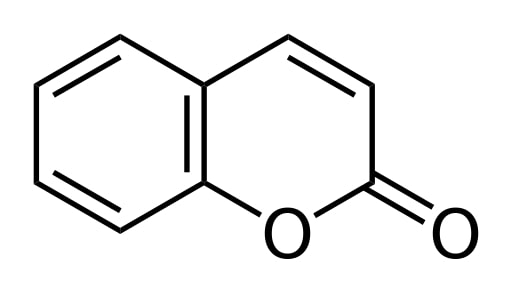

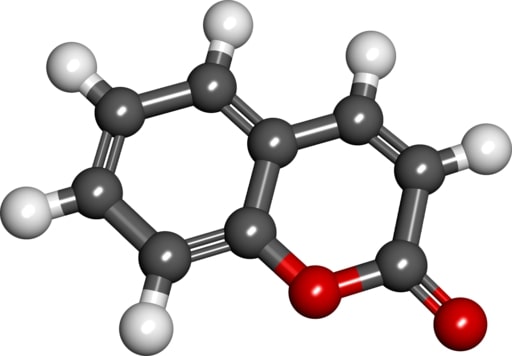

Sarrapia by-products: Coumarin

Coumarin is extracted from the seed using spectrophotometric methods.

Coumarin is an organic chemical compound of the benzopyrin family, which is used in medicine as a powerful blood thinner in blood vessels and to treat some heart conditions.

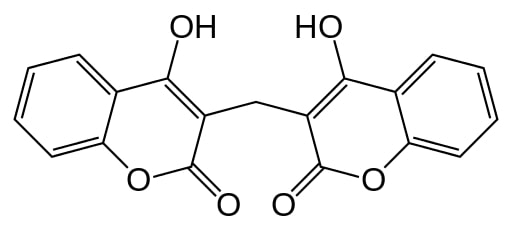

Coumarin itself does not have anticoagulant properties, but the action of certain fungi transforms it into the natural anticoagulant dicoumarol.

Coumarin is used as a medicine in very measured doses to treat tumors, arrhythmias, inflammation, severe pain, osteoporosis, HIV, but it has its drawbacks, because it is toxic to the liver and kidneys.

Some legislations restrict its use as a food additive, although in doses not exceeding 6 mg for a 60 kg person.

Coumarin can be found in several plants. One of them is cinnamon bark, which has, like sarrapia, its contraindications.

But the differences in the coumarin contents of the products must be distinguished. For example, cassia cinnamon (Cinnamomum cassia) has 63 times more coumarin than Ceylon cinnamon (Cinnamomum verum).

Other industrial uses of sarrapia

The sarrapia has a penetrating and pleasant odor. For this reason it is used as a flavoring substance, in tobacco, perfumes and in some foods, generally sweet.

It is somewhat similar to vanilla, but its flavor has a stronger odoriferous personality.

Where is it found in the wild?

The sarrapia grows wild in the jungles of Bolivar State (Venezuela), where its seed is collected and exported to France, Germany and the United States since the mid-nineteenth century.

Harvesting was carried out by indigenous laborers belonging to the Mapoyo group in the Middle Orinoco and Caura regions.

In addition, settlers coming from distant places such as Falcón state joined in the work.

In this Guiana area there are large patches known as sarrapiales. Since 1875, temporary camps, known as sarrapier stations, were erected near the collection sites, which were dismantled every one or two years, according to changes in the sites and in the seed collection season.

The Mapoyo: natives who exploit sarrapia

The Mapoyo is an indigenous group of Caribbean linguistic affiliation that inhabits the region of the middle part of the Orinoco River, between the Suapure and Parguaza rivers, in southern Venezuela.

They are concentrated in the town of El Palomo, in the state of Bolivar, but they are a population that has been shrinking, with no more than 400 members, where there are few speakers of the original language.

Commercial companies were set up in the harvesting areas to buy the collected seeds, as well as chicle and balatá. These commercial agents were inducing the Mapoyo to adopt urban customs, to the detriment of their indigenous culture.

Exploitation and export of sarrapia

The sarrapia stations formed a vast network of substations and a central station linked to the river port of Ciudad Bolívar, from where the sarrapia seeds were exported.

The network covered several areas: the Caura area, with its center in Maripa; the Cuchivero area, with its center in Candelaria and Caicara; and the Middle Orinoco area, with its center in the town of Túriba, connected to the Suapure River.

During the harvesting season, workers would go into the jungle for four to five months each year, because the journeys were long and difficult.

The harvesting cycle began in late January or early February and lasted until April, when the rains began and travel in the jungle became very arduous.

Maestre / CC BY-SA

Back at the camp, the collectors would separate the seed from the fruit, using stones, hammers or machetes.

The seed was dried in the sun, lost weight and took on a dark color and a wrinkled appearance. The Sarrapier stations began in the 1960s, when the business passed into the hands of the central government, through the National Agrarian Institute.

But the world market for sarrapia seed was already in decline due to the emergence of synthetic substitutes.

Dr. Rafael Cartay is a Venezuelan economist, historian, and writer best known for his extensive work in gastronomy, and has received the National Nutrition Award, Gourmand World Cookbook Award, Best Kitchen Dictionary, and The Great Gold Fork. He began his research on the Amazon in 2014 and lived in Iquitos during 2015, where he wrote The Peruvian Amazon Table (2016), the Dictionary of Food and Cuisine of the Amazon Basin (2020), and the online portal delAmazonas.com, of which he is co-founder and main writer. Books by Rafael Cartay can be found on Amazon.com

This post is also available in:

![]() Español (Spanish)

Español (Spanish)