In a novel I once read that the tapir (Tapirus terrestris) was created in God’s distraction. It is a mysterious animal that hardly anyone calls it by its proper name of tapir, but by other names such as danta, vacahuagra, sachavaca, mboré, mborebi, subo rebi, vaca moche, anteburro, capucica, cascuji .

Its tapir name comes from the word tapiich , a name given to it by the Cainguá or Kaingang indigenous people, belonging to the Guarani ethnic group.

It is, without a doubt, a perfect animal to build children’s riddles: it is a horse and a rhinoceros without being any of them, it looks like an elephant and it is not, and from a distance, stuck in the river, frolicking in the water, it has the air of a hippopotamus.

It is an animal that looks like a caricature made with leftover pieces of others. A strange animal not yet discovered by the creators of cartoons, and that competes with marsupials and penguins in rarity, but that human beings are determined to erase them from the face of the Earth, preying on it, without any justification.

Origin of the South American Tapir

The tapir is one of the surviving mammalian species of the neotropical megafauna. It has existed for about 40 million years, and is related to equids and rhinoceroses (Wisuma, Cicha 2011).

The kinship comes from the fact that all equids (horses, donkeys and zebras) and rhinoceroses, like tapirs, belong to the order Perissodactyla, mammals that have extremities with an odd number of fingers or hooves.

The tapir is a fairly primitive animal belonging to the Tapiridae family, of the Perissodactyla order. The genus Tapirus inhabited Eurasia during the Eocene, about 55 million years ago. It spread during the Miocene throughout Eurasia and North America, when the biomass necessary for its food was exhausted.

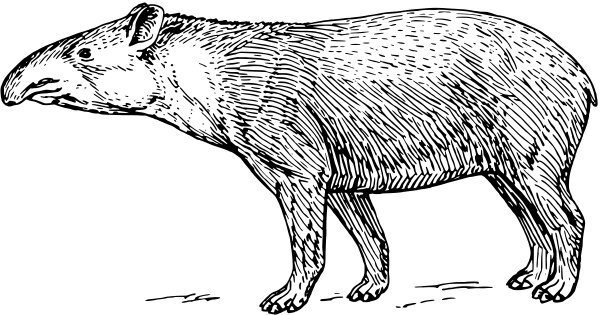

Public domain

The union of the portions of South America with Central and North America, about 3 million years ago, allowed the species of the genus to inhabit the forests of South America.

The tapirs that remained in Eurasia disappeared from Europe and much of Asia due to the ice ages. Only one species survived in Asia: the Asian or Malayan tapir, Tapirus indicus , which inhabits the areas of Sumatra and southern Indochina.

In the Miocene, beginning about 23 million years ago and ending about 5 million years ago, the ancestors of the South American tapirs that inhabited North America migrated to South America.

Neotropical tapir species had diverged about 21 to 25 million years ago. Later, in the Quaternary (beginning 2.59 million years ago and continuing to the present), there was a new separation, now in the high forests of the western Amazon, between the tapir lineages that we know today (Hollande et al. 2011: Pivetta 2011).

taxonomic description

Scientific names of Tapir species

Four subspecies of tapir have been recorded on the planet: Tapirus terrestris , T. pinchaque, both from South America, T. bairdii , from Central America, and T. indicus, from the Malay Archipelago, the insular part of Southeast Asia.

In this article we will focus on the T. terrestris , the most common in South America, and the one with the greatest geographical distribution, present throughout the Amazon basin and, in general, throughout South America, except for Chile and Uruguay, which is why it is known as the Amazonian tapir, although it is also called the Brazilian tapir.

andean tapir

The T. pinchaque , or mountain tapir, is smaller in body than the T. terrestris , and with darker, dense and abundant fur, to withstand the cold of the moors, while the T. indicus, known as the Malayan or Asian tapir, is larger and has black and white fur.

subspecies

Some researchers, such as Arias-Alzate, Palacio-Vieira and Muñoz-Durán (2009), mention two subspecies of Tapirus terrestris in Colombia: Tt aenigmaticus , in southeastern Colombia, and Tt colombianus , in the lowlands of northern Colombia.

Endangered species!

All subspecies have faced critical survival states, all classified as “endangered”, according to the IUCN, except for the Amazonian tapir considered “vulnerable”.

The tapir is very sensitive to pressure from hunting , from which it is difficult to recover due to its visual exposure (a bulky body and routine life habits along very marked trails) and its reproductive behavior (the female gives birth to a single offspring, exceptionally two, after a gestation of about 13 to 14 months ).

The Amazonian Tapir

The tapir ( T. terrestris) is a mammal of the Tapiridae family, the largest in South America, ungulate, with a robust and cylindrical body, with a curved profile, as it is higher on the rump than on the back, with a cross height 110 cm.

It measures an average length of 2 m. and even up to 2.5 m, and reaches a weight between 200 and 270 kg. It has a short tail, about 8 cm on average. Its body, whose skin is hard and resistant, has an ashen-brown coat.

It has a crest on the top, like a mane, made up of long, hard, bristly hairs. Its legs are short, in relation to its heavy body.

It has four toes on its forelegs and three on its hind legs.

Trunk

One of the most striking parts is its elongated upper lip, which joins with the nose to form a prosbocis, long snout or small, curved and mobile trunk.

This prosbocis, which does not exceed 17 cm, is composed almost entirely of soft tissues, so it is very flexible and moves in all directions, allowing it to eat foliage on branches that are difficult to access.

Because of its relatively short trunk, some call the tapir a “miniature elephant” (Richard, Juliá 2000; Constantino et al. 2006; Wilson, Reeder 2005; Montenegro 1998).

View

The tapir has poor, monocular vision. The eyes are small and deep set, with thin lids.

Smell

The visual deficiency is largely compensated by very acute hearing and smell. They detect odors from a distance. To do this, they raise their trunk and show their teeth, which is known as the flehmen reflex.

Teeth

Its dentition is made up of 44 teeth, an element that shows its resemblance to a horse.

Legs and other similarities with the horse

With the horse it also shares other characteristics, such as the shape of its legs and the composition and number of its nails, like a hoof, four in the front and three in the back, or the lack of a gallbladder or its monogastric state. with guttural sacs and non-lobulated kidneys.

Tapir Habitat and Behavior

The tapir chooses its habitat according to two main factors: the availability of food, especially palm drupes, and the availability of water resources (Medici 2010).

It is a solitary animal, with nocturnal habits. It is very dependent on water. He is a good swimmer. The water is used to mate, flee from predators, cool your body.

It needs the proximity of water to defecate, since water acts as a stimulating and regulating element of its excretory function.

Water also helps regulate your body temperature, which is important because of the thickness of your skin. It completely submerges itself in the water for several minutes, and walks on the bed of the body of water, as rhinos do.

The tapir copulates in and out of the water, but close to it. In the water it achieves a certain “weightlessness” that makes it easier for it to mount the female.

The tapir is a great solitary walker, making marches of up to 10 km a day, opening trails, which it knows in detail, which can harm it, but also favor it, because there are places that are difficult to access for other species, and it can better defend itself against their predators. It moves with apparent slowness, but with great resistance, unless it feels pressured. He will then violently charge at the target, using his bulk and quick reactions.

The tapir is a relatively calm animal, unless it feels threatened. Then it will honor the name of “great beast”, with which the Spanish of the colonization knew it.

What does the tapir eat?

The tapir is herbivorous-frugivorous. His diet is actually largely vegetarian. It has a small and simple stomach, but it has a very voluminous cecum in the intestine that houses bacteria that facilitate the digestion of cellulose, which is difficult to digest, and that allows it to feed on small amounts of food several times a day.

In the wild, it feeds on leaves and tender shoots of shrubs and trees , herbs and grasses, and fruit . Studies on tapir feces have found remains of some 122 plant species, belonging to 68 genera and 32 families, evidencing the breadth of their vegetarian diet (Castellanos, Vallejo 2017).

Chalukian, Bustos, Lizárraga 2012 found that the most consumed foods were fibers and leaves, in 84%, and fruits in 16%. In the dry season, a large percentage of seeds was found in their feces, mainly due to the availability of Fabaceae fruit species (Galetti, Keuroghlian, Hanadal, Morato 2001; IUCN/SSC).

Due to its type of consumption, the tapir behaves as an excellent seed disperser over long distances.

In captivity , in zoos, the adult tapir consumes almost 4 kg of alfalfa, about 10 kg of balanced feed for animals, 5 to 12 kg of fruits and vegetables every day.

In freedom it consumes about 9 to 10 kg of food per day. Apart from being a seed disperser, it also preys on them, due to its habit of defecating in the water, reducing the viability of the defecated seeds. To a large extent, the tapir still plays an important role in the conservation of ecosystems in South American humid forests (Cruz 2012).

As for its life cycle, the tapir has a longevity of about 30 years in the wild, and a little more in captivity, where it lives for about 35 years.

It is interesting to note that the tapir plays a great role in the life of the forest, not only as a seed disperser and an agent that maintains the ecological balance, but also as a “builder” of the landscape, by developing trails in the intricate forest . Taber et al (2008) call it “landscape architect or engineer”.

reproductive behavior

The tapir reaches its sexual maturity, in captivity, between 12 and 14 months of age, and breeds around 3 years of age.

In wildlife, reproduction occurs after 4 years of age. There is no seasonality in their reproductive activity. The period of estrus (heat) of the female is short, no more than five days, and repeats every 28 to 32 days.

At that time mating occurs. The courtship is made in romps of male and female, long chases during the night, frequent rubbing of skin, the male nibbles the female’s ears. They make high-pitched, snorting sounds. The genitals are sniffed, snout blows against the belly, until copulation occurs, in or out of the water, in a very short period of time, not exceeding seven minutes.

Then the gestation period of the female lasts about 405 days, that is, between 13 and 14 months.

baby tapir

The female chooses a warm and quiet place to give birth. In each litter one calf is born, very rarely two, which after a few hours is already standing.

It weighs, at birth, from 3 to 6 kg, is about 60 cm long, and reaches a height of 33 cm.

The calf is suckled by the mother for a year or a little less, but begins to incorporate solid foods into its diet from seven days after birth.

Then, it becomes an adult from three to four years of age.

tapir predation

The tapir is an animal at risk, vulnerable for some and endangered for others. However, researchers of the species are unanimous in saying that tapirs are no longer seen in areas where they were abundant. In Argentina, for example, where the tapir is considered a symbol, it has almost disappeared.

In the jungles of the Amazonian regions the presence of the tapir is increasingly rare.

The enemies of the tapir are many, as for any animal of the forest in the Amazon basin, especially for the larger animals , that are more visible due to their size, that require more food and require more territorial space, and that have a low reproductive rate and a long gestation period (Wisuma, Cicha 2011).

The advanced deforestation exposes them and reduces their survival area, especially for a species that has a low density of animal population per km2.

The tapir must, therefore, face diverse enemies. Direct enemies such as poachers and illegal hunters .

Cruz, Paviolo, Bó, Thompson and Di Bitetti (2014) point out that the probability of detecting tapirs increases in relation to the distance from the closest points for poachers, and decreases with the abundance of bamboo plants in the undergrowth and in the forest. the trails you walk on.

Poaching is one of the main factors that marks the habitat of tapirs, although not in their daily life (Ferregueti et al. 2017; Tapia et al., 2000. ).

They are also preyed upon by some hunters from the native indigenous communities themselves who kill them to appropriate their leather and consume their meat, liver, tongue and head.

The meat is roasted or dried in the sun, cut into strips and salted to preserve it as jerky. The Guarani Indians grind the meat to prepare one of their typical dishes , or simply cook it.

The thick leather, of great resistance, is commercialized among the artisans to make belts, purses, soles of sandals, whips.

There are also indirect enemies, which are even more damaging. It happens with the deforestation of the forest, the burning , the illegal extraction of wood and the expansion of extensive cattle exploitations in areas inhabited by tapirs (Arias-Alzate, Palacio-Vieira, Muñoz-Durán 2009; Tapia et al. 2000). Other enemies are their jungle predators like the jaguar, the puma, the anaconda , the alligators.

Due to improvisation, overhunting and disobedience of the species’ protection regulations, the tapir has disappeared, or its population has decreased, in many Amazonian regions and in others where it abounded, such as in some Argentine provinces.

This happened, for example, in the Argentine provinces of Corrientes, Entre Ríos and Tucumán, and efforts are now being made to reintroduce it (Di Martino, Jiménez-Pérez, Peña 2015). Or in Venezuela (Rooms 1996)

Indigenous symbology associated with the tapir

There is a wide symbology associated with the tapir and its representations among the Guarani Indians. Some of the indigenous names for the tapir are mboré and mborebi.

The Milky Way in Guarani astronomy, in Mborebi, is called Rape or Tapi ‘i Rapé , which means “path of the tapir”, in the belief that it corresponds to the celestial fence that surrounds the indigenous farm , where a mythological tapir waters it and take care of the harvest in heaven.

For the Kaingang indigenous people, who inhabited Argentina and Brazil, the origin of the tapir dates back to the great flood or universal deluge that covered the entire Earth. As the waters receded, the few survivors began to draw the new animals with charcoal.

But one of them, deaf, did not listen when they explained to him how to eat, and had to settle for eating foliage from the trees.

Is tapir meat eaten?

All the Amazonian indigenous groups have taboos, including some related to food, as a protection strategy for survival.

In the case of food, it is a strategy to overcome the anguish of food choice for an omnivorous being, who debates, to build his diet, between neophilia, the need to procure new foods to expand his diet, and neophobia, avoid foods that are not toxic, and that create certain precautions that end up becoming food taboos .

These taboos are prohibitions that are incorporated and codified in the rites of the group and inscribed in the performances of the social group. Apart from that, prohibitions are established to consume meat from animals that have a special significance for the group.

For example, the consumption of tapir meat is prohibited in many Amazonian indigenous groups. For example, the Mayoruna, Campa or Achuar ethnic groups do not consume tapir meat, due to the symbolic role that this animal plays in their respective cultures .

The tapir in Ecuador

For the Achuar, from the Ecuadorian Amazon , almost all mammals are edible, with some exceptions, such as the prohibition of eating tapir or sachavaca meat, red deer, capybara or capybara, citing some reason. But they are not fixed prohibitions, but they can change.

There are also differences in consumption behavior among indigenous people.

The tapir in Brazil and Venezuela

Among the Wari, or Bari, of the Brazilian – Venezuelan Amazon, edible animals are divided into two large groups: those with jam and those without.

Having jam is equivalent to having spirit: shadow, image, a double. In this case, they are edible, as is the case with the tapir, the red deer, the jaguar, the monkey. Hence, the Bari only hunt the animals of the forest that they can eat, from the point of view of their culture (Belaúnde 2008:99-100) . It’s about hunting taboos. In other cases, food consumption taboos are applied directly. As do the Mayoruna, who do not consume tapir meat (Erikson 1994: 55).

The tapir or tapir is closely related to the cosmovision of several indigenous ethnic groups of Venezuela, to the point that it can be considered a totem animal for the Piaroa, located on the banks of the Orinoco River, and is held as a deity among the members of the ethnic group Yanomami , in the Venezuelan state of Amazonas. It is particularly relevant that in an urban myth staged by the goddess María Lionza, she rides a tapir.

Tapir Coloring Pages

Bibliography

- Arias-Alzate A., Palacio-Vieira A., Muñoz {Durán J. (2009). New records of distribution and habitat offers of the Colombian tapir ( Tapirus terrestris colombianus) in the northern lowlands of the Cordillera Central (Colombia). Neotropical Mammalogy. Vol. 16 (1), Jan-Jun, 19-25. PDF

- AZA. (2013). Manual for the care of tapirs (Tapiridae). AZA Silver Spring MD Font

- Belaunde LE (2008). Moon’s memory Gender, blood among the Amazonian peoples. Lima: CAAAP. PDF

- Castellanos A., Vallejo AF (2017). tapirus terrestris , In: Brito J., Camacho MA, Romero V., Vallejo AF (Eds.). Mammals of Ecuador. Quito: Museum of Zoology. Pontifical Catholic University of Ecuador. Source

- Chalukian SC, Bustos S., Lizárraga L., Varela D., Paviolo A., Quse V. (2009). Action plan for the conservation of the Tapir (Tapirus terrestris ) in Argentina. Argentina: Tapir Specialist Group. Tapir Research and Conservation Project. NOA/ Wildlife Conservation Society/ Secretary of the Environment and Sustainable Development of the Nation. PDF

- Chalukian, SC, Bustos S., Lizarraga RL (2013). Diet lowland tapir ( Tapirus terrestris ) in El Rey National Park, Salta, Argentina. Journal Zoology, London, 222, 121-128. Source

- Constantino E., Lizcano DJ, Montenegro O., Solano C. (2006). common danta Tapirus terrestris . , 106-112, In: Rodríguez J, Albarico J., Trujillo M., Jorgensen J. (Eds.). Red Book of Mammals of Colombia. Bogotá: Ministry of the Environment, Housing and Territorial Development.

- Cross MP (2012). Density, habitat use and daily activity patterns of the Tapir (Tapirus terrestris ) in the Misiones green corridor. Argentina. Neotropical Mammalogy., Vol. 19 (1), January-June, 179-195. PDF

- Cruz P, Paviolo A, Bo RF, Thompson J, Di Bitetti MS (2014). Mammalian Biology, November, Vol. 79 (6), 376-383. PDF

- Di Martino S., Jiménez-Paez I. Peña J. (2015). Reintroduction strategy for tapirs (Tapirus terrestris) in the Iberá nature reserve (Corrientes, Argentina). The Conservation Land Trust Argentina. PDF

- Erikson P. (1994). The mayoruna. In: Santos Granero, F., Barclay F. (Eds.). Ethnographic Guide to the Upper Amazon. vl. II, 3-127. Quito: FLACSO Ecuador-IFEA. PDF

- Ferreguetti AC, Tomas WM, Bergallo HG (2017). Density, occupancy, detectability of lowland tapirs ( Tapirus terrestris) Vale Natural Reserve Southeastern Brazil. Journal of Mammalogy, 98(1), 114-123. PDF

- Galetti M, Keuroghlian H, Hanada L, Morato MI (2001). Frugivory and dispersal seeds of the lowland tapirs (Tapirus terrestris) in Southeast Brazil. Biotropica, Wiley Online Library. PDF

- Hollande EC et al (2011). New Tapirus Species (Mammalia: Perissodactyle: Tapiridae) from the Upper Pleistocene of America, Brazil. Journal of Mammalogy , Vol. 92(10), 111-120. PDF

- Fauna inventory of the Chuao cocoa valley, Aragua State, Venezuela, 143-151, In: Polanco R. (Ed.). Management and conservation of wildlife in the Amazon and Latin America. Bogota. Source

- Medici E. (2010). Assessing the viability of lowland populations in a fragmented landscape. PhD Thesis. London, Kent University. PDF

- Montenegro OL (1998). The behavior of lowland tapir (Tapirus terrestris) at natural mineral lick in the Peruvian Amazon. MSc Thesis. Gainsville: University of Florida. Source

- Pivetta, M. (2011). A prehistoric tapir. FAPESP research. Edition 185, July. Source

- Polanco R. (Ed.). (2000). Management and conservation of wildlife in the Amazon and Latin America. Bogota. PDF

- Richard E., Julia J.P. (2000). General aspects of the biology, status, use and management of the tapir ( Tapirus terrestris) in Argentina. rhfm, Notes Series No. 1, National University of Tucumán, Horco Molle Experimental Reserve. Faculty of Natural Sciences and Miguel Lillo Institute. PDF

- L.A. Rooms (1996). Habitat at use by lowland tapirs (Tapirus terrestris) in the Tabaro River Valley, Southern Venezuela. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 74, 1452-1458. PDF

- Taber A, Chalukian S, Altritcher M, Minkowsky D, Lizarraga RL (2008). The system of the architects of the neotropical forests. Assessment of the distribution and conservation status of Labiated peccaries and lowland tapirs. New York/ SSC/ IUCN Specialist Group on Tapirs/ Wildlife Conservatios Society/ Wildlife Trust. Source

- Tapia A., Nogales F., Zapata-Ríos G., Tirira DG (2001). Amazon tapir. Tapirus terrestris., 104-141. In: Tirira DG (Ed.). Red Book of Mammals of Ecuador. Quito: PUCE/ Ministry of the Environment. PDF

- Tobler W.W. (2008). The ecology of the lowland Tapir in Madre de Dios, Peru: using new technologies to study large rainforest mammals. Doctoral Thesis. Texas, Texas A&M University. PDF

- IUCN/ SSC. (2010). National Strategy for the Conservation of Tapirs (Tapirus spp.) in Ecuador. Quito: IUCN/SSC. Tapir Specialist Group. PDF

- Wilson D, Reeder D (2005). Mammal species of the world, taxonomic and geographic reference . 2 vols. 3rd. ed. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press. Source

- Wisuma G., Cicha A. (2011). The indiscriminate hunting affects the extinction of the Danta or Tapir. Thesis. RE Equinoctial Technological University, Puyo, Ecuador. PDF

Dr. Rafael Cartay is a Venezuelan economist, historian, and writer best known for his extensive work in gastronomy, and has received the National Nutrition Award, Gourmand World Cookbook Award, Best Kitchen Dictionary, and The Great Gold Fork. He began his research on the Amazon in 2014 and lived in Iquitos during 2015, where he wrote The Peruvian Amazon Table (2016), the Dictionary of Food and Cuisine of the Amazon Basin (2020), and the online portal delAmazonas.com, of which he is co-founder and main writer. Books by Rafael Cartay can be found on Amazon.com

This post is also available in:

![]() Español (Spanish)

Español (Spanish)