Ayahuasca is a sacred or master plant of the Amazon, which was identified for the scientific world by the British botanist Richard Spruce in 1851.

It was found among Amazonian indigenous groups settled along the banks of the tributaries of the Rio Negro in Brazil, in the Orinoco River waterfalls in Venezuela, and in areas of eastern Peru and Ecuador (Trujillo et al 2010).

Dr. Rafael Cartay is a Venezuelan economist, historian, and writer best known for his extensive work in gastronomy, and has received the National Nutrition Award, Gourmand World Cookbook Award, Best Kitchen Dictionary, and The Great Gold Fork. He began his research on the Amazon in 2014 and lived in Iquitos during 2015, where he wrote The Peruvian Amazon Table (2016), the Dictionary of Food and Cuisine of the Amazon Basin (2020), and the online portal delAmazonas.com, of which he is co-founder and main writer. Books by Rafael Cartay can be found on Amazon.com

Ayahuasca and indigenous cosmovision

Ayahuasca is part of the Amazonian indigenous cosmovision.

Naranjo (2012: 74-75) refers to beautiful Shuar myths related to the use of this plant.

December 14, 2019

Amazonian myths and legends about ayahuasca

One of them tells that once upon a time there was a very wise man named Natem, who could see the past and foresee the future, but he could not stay in the world, because people have to grow up.

To help them, he left his spirit in a plant. When men drink the water from that plant they can drink the spirit of Natem.

Another myth relates that a wise man appeared to the Quichuas of the Amazon who could easily dominate the tiger and the anaconda. With his penetrating eyes he saw the past and discovered the desires of his predecessors.

One day he said to the men, “I am strength and wisdom, and I bestow the gifts of manhood. I am the spirit of the ancestors whom you should honor.” That said, it became a climbing plant, very resistant, which they call ayahuasca.

The functions of ayahuasca as a sacred or master plant

A sacred or master plant is collected or cultivated for medicinal and religious purposes (Chirif 2016).

It is both a medicine and a spiritual symbol. But it is a special medicine, which cures the person’s ailment from a higher plane, which is the divine world.

It is a master plant because it teaches you and creates the conditions for self-knowledge, integration with the community and access to a superconsciousness.

In the Amazon, ayahuasca is considered a “mother” plant, origin and guide for other plants.

It is a plant that, say the shamans or taitas, has character, personality and intelligence, and transmits knowledge and power (Landaeta-Casanova 2017, Scuro 2015, Luna 1986).

For most Amazonian indigenous groups, illness is the result of an imbalance between body and spirit.

To heal is to restore the lost balance with the help of sacred substances and the intermediation of shamans or healers.

Source: Spirit Vine Retreats[CC BY-SA 4.0].

It is equivalent to what medical science calls homeostasis, the capacity of an organism to maintain a stable internal condition, compensating by self-regulation the exchanges of matter and energy with the exterior.

The knowledge of these sacred plants is jealously preserved in a native Amazonian community by tradition, and transmitted from generation to generation through a special authority, the shaman, who jealously watches over the administration of the substance extracted from the sacred plant, which is pharmacologically called its active principle.

Every drug consists of an active ingredient, which is responsible for the biologically active or pharmacological activity, and an excipient, which is a complement used to achieve the desired form (capsule, ointment, syrup, injection, etc.) and facilitate its preparation, storage and administration.

Ayahuasca is a particular drug, because it alters the central nervous system, producing hallucinogenic effects.

The responsible use of ayahuasca

Using the properties of a sacred plant, such as ayahuasca, to cure an ailment, to know oneself or to communicate with divine energy, is very important, but it has its risks.

This is why it must be performed with the intervention of a true shaman, who knows well the active principles, the doses of the mixture of substances administered and the strategies of recovery of the normality of consciousness to ensure a controlled experience.

Effects

The intake of ayahuasca produces intoxication, vomiting, diarrhea, dehydration, increases the heart rate and causes hallucinations.

The result can be a pleasant or unpleasant experience, and the reading and interpretation of the visions can be highly speculative.

Risks / hazards

Taking ayahuasca in an urban context, for recreational purposes, in uncontrolled doses and without the guidance of an expert “giver”, can carry high risks that compromise the physical and mental health of the consumer.

The reason is very simple: the consumption of ayahuasca produces many effects: physiological (the “purging” involves vomiting and diarrhea and other sensations), psychological (it stimulates extrasensory faculties associated with the sensations of death and resurrection), hallucinatory and telepathic (linked to divinatory or predictive abilities).

These effects depend on the personality and physical condition of the person ingesting it, the intensity of the dose and the context in which the “taking” takes place.

A ritual, which is its natural setting, important in socialization processes in indigenous and mestizo communities, contributes and fixes symbolic representations that are traditionally expressed within a social structure (Sánchez and Bouso 2015:4).

The sacred entheogenic plants

An entheogenic plant is one that causes alterations of ordinary consciousness leading to a “mystical” state or a trance of ecstasy.

The Greek word “entheos” means “within God” or that “brings us closer to our inner God”, and was created in 1979 by the association of three experts in Greek culture or Hellenists C.A. Ruck, J. Bigwood and J.D. Staples, with the mycologist R.G. Wasson and the ethnobotanist J. Ott. Wasson and the ethnobotanist J. Ott, to designate the ancestral medicinal plants that contain active principles, whose ingestion provokes alterations on the central nervous system, modifying certain physiological or biochemical brain mechanisms.

These alterations modify the activity of neurotransmitters related to cognition, state of consciousness and emotional and motivational manifestations linked to behavior (Fericgla 1997).

Among the best known entheogenic plants are ayahuasca, peyote, marijuana, datura, DMT, etc.

The mixture of substances that we know as ayahuasca

Ayahuasca is a concoction made from a mixture of two entheogenic plants. One is yagé or ayahuasca, a liana of the malpigiaceae family that produces the effect of inhibiting monoamine oxidase (MAOI), contained in the liana. Banisteriopsis caapi .

The word ayahuasca comes from two Quechua words: aya, spirit, dead, and huasca, bejuco or rope.

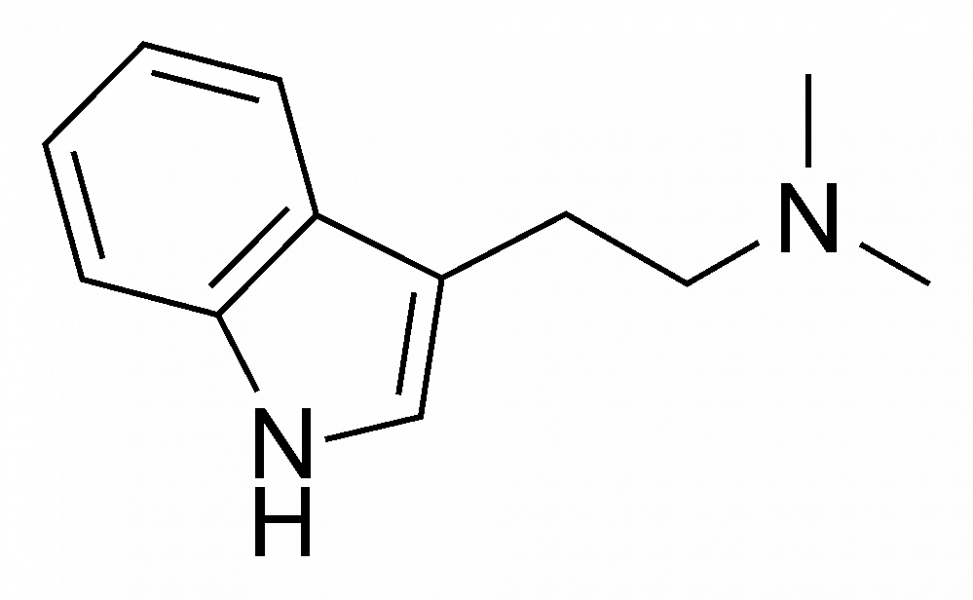

The chacruna = DMT

The other plant is the chacruna(Psychotria viridis), from the rubiaceae family, whose leaves provide the molecule dimethyltryptamine (DMT), responsible for the visions and the increase in potency and duration of the effects (Tupper 2008).

This molecule is found naturally in many plant and animal species, and even in human urine (Barker et al 2012).

The mixture is important, because the presence of the two plants is necessary to produce the hallucinogenic effects attributed to the concoction.

The two substances, ayahuasca and chacruna, act with different pharmacological dynamics when subjected to laboratory tests.

Source: Zoe Helene[CC BY-SA 4.0].

DMT acts immediately, while the effects of ayahuasca appear more slowly, in a progressive manner, 40 to 60 minutes after its administration, reaching its maximum effect after 2 hours, and disappearing its effects after 4 to 6 hours (ICEERS 2017).

Source: Cacycle [CC BY-SA 3.0]

Applied for medicinal purposes, it has been found that the continuous use of ayahuasca produces, in the medium and long term, an increase in the well-being of regular users due to the reduction of physical pain in their ailments.

The mixture to prepare the concoction is not limited only to ayahuasca or yajé combined with chacruna, which provides the DMT molecule.

Other possible mixtures

There are others such as chapilonga(Diploteris cabrerana), a liana of the malpigaceae, which grows in the South American tropical rainforest, and others (Castro et al 2017). The important thing is to find the presence of DMT in the mixture, which provides the stimulating element of the visions.

Ott (1994) cites 97 species belonging to 39 botanical families that can be added to the mixture, which he divides into three groups: 1) Those that, without being psychoactive, have therapeutic value, such as Mansoa allicea or Alchornea castancifolia. 2) entheogenic or visionary drugs, such as Psychotria viridis or Brunfelsia grandiflora, and 3) stimulants, such as Ilex guayusa, Paullinia yoco, Erithroxylum coca Lamarck).

DMT is an entheogen first synthesized in 1931 from two different plants. Years later, DMT was identified as “the first endogenous human psychedelic”, i.e., produced by the human organism itself (Strassman 2001).

It was then learned that DMT is the visionary component of ayahuasca and that it acts on the pineal gland, located in the center of the brain, adding a certain amount of DMT. The same happens with the practice of meditation, dance, music and other cultural expressions close to mystical and spiritual experiences (Strassman 2001).

Neuroimaging studies performed on members of the Santo Daime church, who have a long history of ayahuasca use, at least 50 times in the last two years, found the cortex to be thicker compared to that of a control group.

This difference is correlated with the self-transcendence of the practitioner, suggesting that the regular use of ayahuasca may have caused brain alterations that increased spiritual tendencies (Bouso et al 2015).

A phenomenon similar to that which occurs when there is training and practice in some activities such as music, associated with what has been called brain plasticity.

Specialists maintain that the effects of the use of ayahuasca in moderate doses is psychologically safe. The impact on the cardiovascular system is minimal, producing slight increases in blood pressure and heart rate.

The effects of ingestion are mostly physical: nausea, vomiting, dry tongue, dehydration, known as “purging” or “cleansing”. This emetic or vomiting effect limits the use of ayahuasca as a recreational drink.

The ICEERS (2017:10) technical report on ayahuasca concludes that ayahuasca is a substance with acceptable psychological and psychopathological safety of use and therapeutic potential.

Indigenous cultural use of ayahuasca

The decoction of the mixture of the two plants is used by indigenous and mestizo shamans or shamans to cure illnesses and reveal hidden or underlying stories in the subconscious of the person who ingests it.

The concoction is also used by indigenous youths when performing their initiation rites. Initiation rites symbolically mark the transition from one state to another in a person’s life, such as moving from adolescence to adulthood.

In this case, the young person is subjected to tests and, upon passing them, is reintegrated into society in another condition, that of an adult, with certain rights such as the right to form a family and participate in the decisions of the community. In this process, the initiate takes ayahuasca.

Zones and cultural contexts of ayahuasca consumption

Ayahuasca is traditionally planted and consumed in the native indigenous communities of the northwestern Amazon as an ancestral practice in various indigenous rituals.

It is cultivated in the chacras or chagras by the shaman or taita himself, from medium-sized yage stems, about 60 cm long and 1 to 4 cm in diameter.

How is it prepared?

For the preparation of the concoction, the yagé is cut into pieces and put to cook in water, with chacruna leaves, or the substitute, until the desired point is obtained by the shaman. It is then left to cool, to be consumed the following day. (Beyer et al 2009, Schultes and Raffaud 1994).

Luna (1986a, 1986b) has carried out an exhaustive review, with more than 400 bibliographic references, in which he points out more than 70 indigenous groups that consume, or traditionally consumed it, and a compilation of more than 40 names used to denominate the brew.

Its use is not limited to indigenous peoples, but was extended to mestizo settlements in the Amazon (Labate, Cavnar and Gearin 2017, Labate and Cavnar 2014, Labate and Bouso 2013).

The use of ayahuasca among native indigenous communities is well documented in the Amazonian regions of Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia and Brazil.

In Venezuela, information is lacking, but its use among the Yekwana, under the name khaáhi, was confirmed by naturalist and explorer Charles Brewer-Carías, a specialist in Amazonian flora (personal communication, hotmail, 27.10. 2019). Rodd (2008) does so, in turn, on employment among the Piaroa, in the state of Amazonas, in southern Venezuela.

Schultes and Raffauf (1990) had previously described ritualistic practices with yage among the indigenous people who inhabited the margins of the tributaries of the Orinoco River in the Colombian-Venezuelan Orinoco.

The religious use of yagé

Since the 20th century, its use in some Amazonian cities has expanded, combining syncretic elements of Amerindian shamanism with religious practices of African origin, Christianity and European esotericism.

In this context, certain cults and churches based on the use of ayahuasca among their followers have been created in the Brazilian Amazon since the 1980s (Labate 2004).

From the 1990s onwards these practices expanded internationally, albeit in a limited way (Labate, Jungaberle 2011), particularly to the Netherlands, the United States and some Asian countries (Sánchez and Bouso 2015).

Ayahuasca in the city

On the other hand, the use of ayahuasca for recreational purposes in urban areas of some Amazonian countries, such as Brazil and Peru, has been imposing itself, decontextualized from its natural setting and without the supervision of experienced shamans (Dos Santos 2016, Chávez 2012, Ronderos-Valderrama 2009, Santos 2007, Vélez and Pérez 2004, Lima 2004, Shanon 2005, Pereira 2003, Weiskopf 2002).

The importation of ritual ceremonies with ayahuasca in the Greater Caracas area, with the participation of Colombian taitas, from Putumayo, was documented by Landaeta-Casanova (2017).

Beginnings of ayahuasca consumption in Amazonia

It is not known precisely since when ayahuasca has been consumed in Amazonian indigenous rituals or as medicine, although there is talk of millennia. One of the most remote evidences of its use was found in the Azapa Valley, in the region of Arica, in northern Chile.

Analyzing mummies from the Tiwanaku period, between 500 and 1,000 C.E., archaeologists found harmine residues in the funerary remains. As there are no harmine-producing plants there, such as Banisteriopsis caapi, it is believed to have arrived by commercial exchange, which included ayahuasca (ICEERS 2017).

The combined use of ayahuasca with chacruna, which contains DMT, is, according to some, a relatively recent Amazonian use, which has been catching on (Brabec de Mori 2011). Although the mixture was rediscovered by scientists in the 1980s (Riba et al 2015).

The ritual of“The ayahuasca intake“.

Here we are mainly guided by Damasio (1999), Landaeta-Casanova (2017), Díaz-Mayorga (2004), Fericgla (2003) and Marulanda-Mejía and Rico (2003).

The ingestion of ayahuasca, or rather of the bitter, viscous, green-colored concoction derived from the mixture of entheogenic plants called ayahuasca, is done under certain preconditions established by the taita or shaman who conducts the “taking” process.

Preparation before consumption

Among these requirements to facilitate the “purge” or “cleansing”, participants are asked to abstain from sex at least three days before the intake, avoid consuming red or white meats, fats, onions, garlic, spicy foods, alcohol, etc.

The drinking is generally done at night, around seven o’clock, in an almost dark space controlled by the taita, shaman or yachak, who presides over the act, standing behind a small table, where the container containing the brew is placed, and next to it perfumes, flasks, and the chondur, a mixture to assist the participants and calm them down.

Utensils

The taita wears a long tunic or cuhsma, carries a crown of feathers, a long necklace, and uses various utensils that reinforce his action, such as a bundle of dry leaves (huairasacha), a rattle, an incense burner, a maraca, etc.

It is accompanied by soft music from a musical instrument, the chakapa, or a percussion instrument, a drum, or strings or a flute or harmonica. The staging, or setting, is very similar to that of a Catholic priest at mass.

At the beginning, the taita explains very briefly the purpose of the act, saying, words more, words less, that ayahuasca is a sacred plant, a sacred plant that orders the mind and allows you to know yourself inside and heals you inside.

When you take it, you may feel like vomiting or diarrhea, but it is cleansing or purging you from the inside. Another taita (Colombia) or yachak (Ecuador) explains, according to a report by Carlos Nova, in the newspaper El Telégrafo, of Guayaquil, Ecuador, on February 25. 2019, that the “mission of ayahuasca is to accept the things you cannot change, such as death and the past, and to take care of emotions above all.” And “cleanse and reorganize the mind and body”.

Monkfish powder

At the beginning of the ceremony, the taita “projects” monkfish powder through the nostrils of each participant, which consists of ground, flavored tobacco. In the meantime, the atmosphere is perfumed with incense of different aromas (palo santo, cedar, rosemary, sage, myrrh, tobacco, etc.).

The first glass

The taita offers the first cup, a small portion, to each participant, who ingests it, one by one, in the order established by a queue. When handing the cup, the taita blesses it and blows it (in the blowing the taita transfers his intention and energy to the ayahuasca).

The cup contains a thick, brownish-brown concoction with a molasses-like, sweet to bitter taste. Then the participant takes his or her place again, waiting for the effects of the concoction to take place, while the taita says ícaros, or chants that are like prayers in Quechua or Spanish.

Source: Sascha Grabow www.saschagrabow.com [CC BY-SA 3.0]

In the first 15 to 20 minutes the effects begin to be triggered. You feel a kind of tingling in your body. The physical effects are then presented: increased heart rate and respiration, dizziness, vomiting, diarrhea, varying according to the characteristics of the participants.

If the initial physical effects are not present, the taita offers a second cup to the participant.

The effect of the intake can last from 1 to 3 hours, during which time the participant enters a state of trance or expanded consciousness, in which, without losing awareness of the environment, he/she participates in visions, although afterwards it is difficult for him/her to express in detail and with clarity the experience he/she has lived.

Visions

Comparative studies have been made on the visions that appear as an effect of taking ayahuasca.

They are images that are progressively composed, as if they were fragments that are being integrated. It begins by perceiving different colors and geometric figures that rotate or kaleidoscopic images, which are organized into concrete visions (animals, plants, people, landscapes).

Marulanda-Mejía and Rico (2003) point out that visions behave like archetypal images, in the manner of Jung, i.e., they are very similar in all cases of perceptions. For example, eagles, tigers, snakes are repeated .

The legal status of ayahuasca

Both ayahuasca and chacruna contain alkaloids, which are psychoactive substances registered in the 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances.

However, neither ayahuasca nor chacruna are subject to international control according to the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB), a quasi-judicial body admitted to the United Nations Drug Conventions, which preserves and defends indigenous ancestral practices and their modes of ritual.

Ayahuasca was declared a cultural heritage asset of Peru, due to its use in ancestral rituals and as a traditional medicine of the Amazonian indigenous peoples.

In addition the use of ayahuasca for religious purposes is common and legal in Brazil (Labate, Cavnar and Gearin 2017, Cauiby 2000). Its use for religious purposes in the Netherlands and certain U.S. states is also permitted, although subject to regulation and supervision.

How and where to take it in a controlled manner?

In the Bolivian Amazon, in the north of the country, there are ecological tourist lodges, such as the Pisatahua Lodge, where ceremonies are performed with master plants such as ayahuasca, coca, San Pedro and spiritual retreats are organized.

The use of ayahuasca is also not expressly controlled in Spanish legislation, by the Medicinal Products Agency.

The use of ayahuasca as a basis for socialization or as a recreational drug in urban centers, employed by young people (Scuro 2017, Shannon 2005, Silveira et al 2005, Vélez and Pérez 2004, Uribe 2002).

The celebration of cults or religious practices, with a syncretic mixture that unites several spiritual currents, is widespread in the Brazilian Amazon, with churches such as the Santo Daime, the Union do Vegetal (UDV), the Barquinha. The same is happening in Peru and Colombia, with the expansion of the Vegetalism current.

Ayahuasca religions

Santo Daime originated in a group of followers of Raimundo Irineu Serra, “Padrinho Irineu”, in the Brazilian Amazonian city of Céudo Mapiá, in the state of Acre, in 1920, where its main spiritual center is located (Labate et al 2002).

Ayahuasca is used as the ritual drink of religious practice, until a state of collective ecstasy is reached.

Upon Serra’s death in 1971, followers expanded the ayahuasca religion in other Brazilian states and outside the country (Lowell and Adams 2016, Lopez 2015, Dawson 2009, Goulart 1996).

The Union do Vegetal (UDV)

The Union do Vegetal (UDV) was created by the ex-capoerista José Gabriel Da Costa, in 1961, with headquarters in Planaltina, in Brasilia D.F.. It has more than 7,000 members and is the best organized ayahuasca religion.

It is a reincarnationist Christian version of religion, with elements of Alain Kardec’s spiritualism and other urban religious manifestations.

It has a hierarchical structure (body of instructors, counselors, teachers) and even a medical department composed of psychiatrists, who do research on ayahuasca (Laqueille and Martins 2008, Labate 2004, Labate et al 2002).

The Barquinha

Barquinha was created in Rio Branco, in the state of Acre, by Daniel Pereira de Matto in 1945.

It is an eclectic congregation, where baptisms, concentration dances, indoctrination of souls and pilgrimages take place (Labate 2004).

It maintains a local presence, limited to Acre, while the other two churches have expanded to the United States, Canada and Europe, with Brazilian migration (Silveira et al 2005).

Pharmacological, medicinal uses

Ayahuasca or yagé contains beta-carbonyl alkaloids, such as harmaline, harmine, yagenine and tetrahydroharmine, which have antimicrobial, antihelminthic, antidepressant and vasodilator properties, and are used pharmacologically for various medical purposes, including epilepsy and Parkinson’s disease.

Chacruna, the supplement in the mixture, contains DMT which temporarily inhibits the action of the enzyme monoamine oxidase (MAO). The discovery of these properties prompted the appropriation of its active principles.

The patent and its cancellation.

In 1986 Loran Miller, of the International Plant Medicine Corporation, filed US Patent No. PP 05751 as “a new variety of yage”. At that time there was little research on the plants that were mixed in ayahuasca (McKenna et al 1986).

In 1996 the Coordinating Committee of Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon Basin (COICA) protested the validity of the patent, considering it an act of piracy, and succeeded, in 1999, in having the patent annulled in U.S. court.

Antidepressant

The intake of ayahuasca, as the result of the mixture of two entheogenic plants, has been used in medicine for the treatment of patients suffering from recurrent depression.

In this case, the antidepressant properties of the mixture, and its rapid and sustained action are used (Sanchez and de Lima-Osório 2016, Dos Santos et al 2016, Mazar 2014, Herraiz et al 2010, Gallego 2007, Callaway, Brito and Neves 2005, Costa et al 2005, Riba 2003).

The enzyme monoamine oxidase (MAO) is involved in the elimination of the neurotransmitters norepinephrine, serotonin and dopamine from the brain, which are the chemical messengers of communication between brain neurons.

Created with Accelrys DS Visualizer Pro 1.6 and GIMP.(CCby4.0)

When the availability of these neurotransmitters is reduced, changes in brain neurochemistry occur, which favors the onset and development of depression.

Harmine, present in ayahuasca, acts as an MAO inhibitor, preventing this from happening, making it possible to have more of these neurotransmitter chemicals, which are antidepressants (Carlini 2003).

Source: Giorgiogp2 [CC BY-SA 3.0]

Psychotherapy

Fericgla (2003) provides an excellent summary of the use of ayahuasca, since the middle of the 20th century, in ethnopsychology and psychopharmacology, and of its applications in the field of psychotherapy and the development of the potentialities of the human mind.

Gallego (2007) and Echeverri-González (2003) reflect on the implications of psychoactive substances in the expansion of modified states of consciousness (MCE), which transcend the question of “why” to add the question of “what for”.

To overcome strong drug addictions

Apud (2019) refers four cases of successful recovery of patients with severe drug addictions who recovered with successive intakes of ayahuasca and appropriate sociocultural context, applying interdisciplinary approaches. See also: Apud and Romani (2017).

McKenna and Riba (2015) note that ayahuasca administration reduces cognitive constraints on executive functions and increases the excitability of various brain levels in association areas, leading to a psychological state prone to introspection and personal reflection.

To treat Parkinson’s disease

Parkinson’s disease has many symptoms related to the loss of certain groups of neurons in the brain, particularly due to the absence of dopamine. Hence, harmine contributes to inhibit the action of MAO, which increases the concentration of dopamine in the brain.

There are now other drugs that are more effective in producing the MAO inhibitory effect (Samoylenko et al 2010, Caslaxe et al 2009, Schwartz et al 2008, Laqueille and Martins 2008).

Bibliography

- Apud I. 2019. Ayahuasca in the treatment of addictions. Study of four cases treated at IDEEA, from an interdisciplinary perspective. Interdisciplinary. Journal of Psychology and Related Sciences. Vol. 36, 131-154. (PDF)(Source)

- Apud I, Romani O. (2017). Medicine, religion and Ayahuasca an Catalonia. Considering Ayahuasca networks for a medical anthropology perspective. International Journal of Drug Policy. 39, 28-36.(Source)

- Brabec de Mori B. 2011. Tracing Hallucination: Contributing to a critical ethnohistory of ayahuasca usage in the Peruvian Amazon. 23-47. Labate B.C. & Jungaberle H. (Eds.). The Internationalization of Ayahuasca. Zurich: Lit. Verlag. (PDF)(Source)

- Beyer J., Drummer O.H., Maurer H.H., 2009. Analysis of toxic alkaloids in body samples. Forensic Science international, 185, 1-9.(Source)

- Bouso J.C., González D., Fundevila S., Cutchet M., Fernández X. 2012. Personality, Psychopathology, life attitudes and neuropsychological performance among ritual uses of Ayahuasca: A longitudinal study.. P Los One, Vol. 7, 10.371 Journal .pone.0042421.(PDF)(Source)

- Brewer-Carías C. 2013. Naked in the jungle. Survival and subsistence. Caracas: C.B.C.

- Burroughs, W. 1953. Letters from the yagé. Buenos Aires. Ediciones Signos (PDF)

- Callaway J.C., Brito G.S. and Neves E.S. 2005. Phytochemical analyses of Banisteriopsis caapi and Psychotria viridis. Journal of Psychoactive Drug, 37 (2), 145-150. (Source)

- Carlini E.A. 2003. Plants and the Central Nervous System. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior. 75, 501-512. (PDF)(Source)

- Caslaxe R, Macleod A, Ives N, Stowe R, Counsell C. 2009. Monooxidase inhibitors compared with other treatments in early Parkinson’s disease. Cochrane(Source).

- Castro A., Ramos N, Rojas-Armas J., González S., Acha O., Raez J., Ramos D., Hilario-Vargas J. 2017. Psychoactive and Organic Effects of Banisteriopsis caapi and Diploteris cabrerana (Cuatrec.) B Gates in Rats Research. Journal of Medicin Plants, 11 (3), 86-92. (PDF) (Source)

- Caiuby B. 2000. An Overview of Current Use in Contemporary Brazil (PDF)

- Chávez M.G. 2012. The cult of Santo Daime. Notes for the legalization of the use of psychoactive substances in ceremonial contexts in Mexico. San Luis College Journal, 56-89.(PDF)(Source)

- Chirif A. 2016. Amazonian dictionary. Lima: Lluvia Editores-CAAAP.

- Costa M.C., Figuereido M.M.C., Cazenave S.O.S 2005. Ayahuasca: a toxicological approach to ritualistic use. Revista Psiquiatría Clínica. 32, 310-318. (PDF) (Source)

- Damasio A. 1999. The Feeling of What Happens. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (PDF).

- Dawson A. 2009. Positionality and role-identity in a new religious context. Participant observation at Céu do Mapiá. Religión, 40 (3), 173-181. (PDF)(Source)

- Diaz-Mayorga R. 2004. Yagé, a brief ethnomedical description. Therapeutic yage workshop. Shamanic Vision Magazine. (Source)

- Dobkin de Ríos, M. 1970. A note of the use of Ayahuasca among urban mestizo population in the Peruvian Amazon. American Anthropologist, 73, 1419-1422. (PDF) (Source)

- Dos Santos R.G., Osorio F.L., Crippa J.A.S., Hallak J.E.C. 2016. Antideppressive and anxiolytic effects of ayahuasca: A systematic literature review of animal human studies. Rev. Bras. Psychiatry, 38, 65-72.(PDF)

- Dos Santos R.G. 2007. Ayahuasca: neurochemistry and pharmacology. Electronic Journal of Mental Health , Alcohol and Drugs. 3, 1-11. (PDF)(Source)

- Echeverri-González J. 2003. We are going to bloom the roads. Aesthetics and Modified States of Consciousness (MSC). Culture and Drugs, Year 8 (10), 65-82. (PDF) (Source)

- Eliade M. 1976. Shamanism and archaic techniques of ecstasy. Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica. (PDF)

- Fericgla J.M. 2003. Structure-activating experiences in individual and societal development. Culture and Drugs, Year 8 (10), 19-43. (PDF)

- Fericgla J. M. 2000. Shamanism under review. Barcelona: Kairós. (PDF)

- Fericgla J.M. 1997. In the light of ayahuasca. Cognitive anthropology, oniromancy and alternative consciousness. Barcelona: La Liebre de Marzo.

- Gallego O. 2007. Yagé, cognition and executive functions. Culture and Drugs, 12 (14) 13-26.(PDF)

- Goulart S. 1996. Raizes culturais do Santo Daime. MSc Thesis. Sao Paulo, BR. Universidade de Sao Paulo (Source).

- Herraiz T., González D., Ancin-Azpilicuatea C., Arán U.J., Guillén H. 2010. Beta-carboline alkaloids Peganum harmida and inhibitions of vomanmonoamine oxidase (MAO). Food Chemical Toxicol. 48 (3), 839-843. (PDF)

- International Center for Ethnobotanical Education, Research & Service (ICEERS). 2017. Ayahuasca Technical Report. (Bouso J.C., Guimaraes Dos Santos R., Groub C.S., Da Silveira D.X., McKenna D.J., Barros de Araujo D., Riba J., Ribeiro-Barbosa P.C., Sánchez-Avilés C., Caiuby, Labate B.)(PDF).

- Labate B.C. 2004. A reinvencao da uso da ayahuasca nos centros urbanos. Campinas: Mercado de Letras (Source).

- Labate B.C. and Bouso J.C. (Eds.). 2013. Ayahuasca and health. Barcelona: Los libros de la Liebre de Marzo.(Source)

- Labate B.C. and Cavnar C. 2014. Ayahuasca. Shamanism in the Amazon and Beyond. New York: Oxford University Press. (PDF)

- Labate B.C., Cavnar C. and Gearin A.K. (Eds.). 2017. The World Ayahuasca Diaspora: Reinventions and Controversies .Abingdon, England: Routledge. (PDF)

- Labate B.C., Araujo E., Sena W. 2002. The ritual use of Ayahuasca. Campinas: Mercado das Letras, Sao Paulo. (PDF)

- Labate B.C. and Jungaberle H. (Eds.). 2011. The Internationalization of Ayahuasca. Zurich: Lit. Verlag. (Source) (PDF)

- Laqueille X. and Martins S. 2008. L’Ayahuasca: Clinique, neurobiology eet ambigueté thérapeutique. Annales Medico Psychologiques, 166, 23-27.

- Landaeta-Casanova R. 2017. Painting Caracas with the colors of Yagé. The translocalization of Ayahuasca rituals. Undergraduate Thesis. Sociology, School of Economics and Social Sciences. Andrés Bello Catholic University. Caracas, Venezuela (PDF)

- Lima E.G.C. 2004. The ritual use of Ayahuasca from the Amazon forest to urban centers. Practice and research monograph. Cultural Geography. University of Brasilia. UnB. Brasilia.

- Lopez S. 2015. Life as a healing process: shamanic practices of the Alto Ammazonas around Ayahuasca in Spain. Doctoral dissertation. Madrid. Complutense University of Madrid. Faculty of Political Science and Sociology. (PDF)

- Lowell J.T. and Adams P.C. 2016. The routes of a plant: ayahuasca and the global networks of Santo Daime. The university of Texas at Austin. Doll Medical School. 10.1080/14649365.2016.1161818.(Fuente)

- Luna L.E.1986a. Vegetalism Shamanism among the mestizo population of the Peruvian Amazon. Stockholm Studies in Comparative Religion, 27. Stockholm Almqvist and Wicksell International(Source).

- Luna L.E. 1986b. Bibliography on ayahuasca. Indigenous America, 46 (1), 235-245.

- Marulanda-Mejía T., Rico D.C. 2003. Archetypal manifestations with the consumption of yage. Culture and Drugs, Year 8, 10, 43-64.

- Mayo Clinic. 11.2018. Depression. Mayoclinic.org./en-s-s/diseases-conditions/ depression/ in-depth/maois/art-20043992.

- Mazar P.M. 2014. Ayahuasca for beginners. Medical-Social Notebooks. , 49-55. Chile (PDF)

- McKenna D.J., Luna L.E., Towers G.H. 1986. Biodynamic ingredients in the plants that are mixed with ayahuasca. An unresearched traditional pharmacopoeia. América Indígena, 46, 73-101. (Source)

- McKenna D Y Riba J. 2015. New World tryptamine hallucinogens in the neuroscience of Ayahuasca. Current Topics on Behavioral Neuroscience. doi: 10.007/7854_2016_472. (PDF)(Source)

- Ott J. 2005. Pharmahuasca. Ayahuasca and Jurame wine. Culture and Drugs, 7. Manizales, Colombia.

- Ott J. 1994. Ayahuasca analysis: Pangaean Entheogens. Kenewick, WA: Natural Products Co.

- Pereira E. 2003. Ayahuasca: Expansion of these rituals and forms of scientific research. Resen. Revista Brasileira ds Ciencias Sociais.18. 203-207.(PDF)

- Riba J. 2003. Human Pharmacology of Ayahuasca. PhD Thesis. Barcelona : Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona. (Source)

- Ribeiro-Soares A., Sabiao R. and Ferreira G. 2019. Psychology, Religion and spirituality. Psicologia e Sáude em Debate. Electronic. ISSN 2446-922x. Doi: org./10.22289/2446922x.V5S1A2. (PDF)

- Rodd, R. (2008). Reassessing the cultural and psychopharmacological significance of Banisteriopsis caapi: preparation, classification and use among the Piaroa of Southern Venezuela. Journal of psychoactive drugs, 40(3), 301-307. (PDF)

- Ronderos-Valderrama J. 2009. Yagé rituals in urban areas of the Eje Cafetalero: practices and dynamics of interculturality and emerging mentalities. Culture and Drugs, 14, 119-140.(PDF)

- Samoylenko V., Rahman M., Teknani B.L.,Tripathi L.M., Wang Y.H., Khan S.I., Khan I.A., Miller L.S., Joshi V.C., Muhammad I. 2010. Banisteriopsis caapi, a unique combination of MAO inhibitory and antoxidative constituients for the activites relevant to neurodegenerative disorders and Parkinson disease. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 127, 257-367.(PDF)

- Shannon B. 2005. Review of Labate, B.C. A reinvencao do uso da ayahuasca nos centros urbanos. Mana, 11, 593-604.(Source)

- Shanon, B. (2002). The antipodes of the mind: Charting the phenomenology of the ayahuasca experience. Oxford University Press, USA. (PDF)

- Sánchez-Avilés C. and Bouso J.C. 2015. Ayahuasca. From the Amazon to the Global Villages. Drug Policy Briefing. No. 43, Transnational Institute / ICEERS Foundation(PDF)

- Sánchez R.F. and de Lima-Osório F. 2016. Antideppressant effects of a single dose of ayahuasca in patients with the recurrent depression : a SPECT study. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, Vol. 36, 1. (Source)

- Schultes R.E. and Hofmann A. 1979. Plants of the Gods: origins of the use of hallucinogens. Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica (PDF).

- Schultes R.E. and Raffauf R.F. 1994. The bejuco of the soul, the traditional mydicos of the Colombian Amazon, their plants and rituals. Bogotá: Banco de la República. Ediciones Uniandes. Editorial Universidad de Antioquia. (Source)

- Schultes R.E. and Raffauf R.F. 1990. The healing forest, medicinal and toxic plants of the Northwest Amazonia. Portlnd, Oregon: Dioscorides Press.

- Schwart M.J., Houghton P.J., Rose S., Jenner P., Lees A.D. 2003. Activities of extract and constituients of Banisteriopsis caapi relevant to parkinsonism. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and behavior. 75, 627-633.

- Scuro J. 2017. Ayahuasca and (de) coloniality. Effects of the neo-shamanism device as a vehicle for change. Social Sciences and Religion / Ciencias Sociais e Religiao. Porto Alegre, 22, 167-187. (PDF)

- Shephard G.H. 1998. Psychoactive plants and ethnopsychiatric medicines of the Matsigenska. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 30, 321-332. (PDF)

- Silveira E.D., GrobC.S., Dobkin de Ríoss M., López E., Alonso L.K., Tacla C., de Silveira D.X. 2005. Report on psychoactive drug use among adolescents using ayahuasca within a religious context. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 37, 141-144.(PDF)

- Strassman R. 2001. DMT: The Spirit Molecule. Vermont: Park Street Press. (PDF)

- Telégrafo El, newspaper, Guayaquil, 25.02. 2019. Report by Carlos Nova. Ayahuasca: the most famous and respected concoction of the Amazon. (Source)

- Trujillo-Trujillo E., Frausin-Bustamante G.G., Correa-Muñera M.A., Trujillo-Calderón W.F. 2010. The use of Ayahuasca in the Amazon. Ingenierías & Amazonía, 3 (1), 151-163. University of the Amazon. (PDF) (Source)

- Tupper K.W. 2009. Ayahuasca healing beyond the Amazon: the globalization of a traditional indigenous enthogenic practice. Global Neetworks, 9 , 117-136.(PDF)

- Tupper K. W. 2008. The globalization of Ayahuasca: Harm reduction or benefic maximization? International Journal of Drug Policy. 19, 297-303.(PDF)

- Uribe C.A. 2008. Yagé, purgatory and show business. Antipode, 6 , 113-131. (PDF)

- Uribe C. 2002. Yagé as an emerging system: discussions and controversies. CESO Documents, No. 33, 1-65. Center for Sociocultural and International Studies (PDF).

- Vélez A. and Pérez A. 2004. Urban consumption of Yajé (Ayahuasca) in Colombia. Addicciones, 16, 323-334. (PDF)

- Weiskopf I. 2002. Yagé: The New Purgatory. Bogotá: Benjamín Villegas Editores. (PDF)

January 22, 2020

3 scientific studies on ayahuasca

January 16, 2020

4. Great naturalist scientists in the Amazon Rainforest (18th to 19th centuries)

December 14, 2019

Amazonian myths and legends about ayahuasca

November 28, 2019

Amazonian Indigenous People Cosmovision – Beliefs, Taboos, Myths and Legends

November 27, 2019

13 Typical dances of the Amazon (videos, music and movements)

November 17, 2019

Cane Toad / Giant Toad (Rhinella marina)

November 17, 2019

Kambo (Phyllomedusa bicolor)

October 19, 2019

Amazon Rainforest Drinks

This post is also available in:

![]() Español (Spanish)

Español (Spanish)