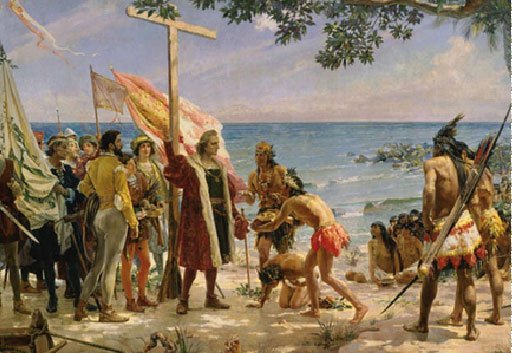

The Iberian, Spanish and Portuguese penetration was expressed with arms, military conquest, and with the cross, evangelization. A penetration that was very bloody in the discovered and occupied territories. The Brazilian case, the largest portion of the Amazon, is even stronger.

“Brazil has always been – still is – a dreadful mill of wasting people, although it is, at the same time, a prodigious cradle of people. Six million Indians existed here when the first European arrived. There are not even three hundred thousand Indians left today.”

According to Darcy Ribeiro (Introduction, IX, Ribeiro and Araújo 1992).

Dr. Rafael Cartay is a Venezuelan economist, historian, and writer best known for his extensive work in gastronomy, and has received the National Nutrition Award, Gourmand World Cookbook Award, Best Kitchen Dictionary, and The Great Gold Fork. He began his research on the Amazon in 2014 and lived in Iquitos during 2015, where he wrote The Peruvian Amazon Table (2016), the Dictionary of Food and Cuisine of the Amazon Basin (2020), and the online portal delAmazonas.com, of which he is co-founder and main writer. Books by Rafael Cartay can be found on Amazon.com

Perspectives of the Spanish and Portuguese Conquest

For Ribeiro, the Iberian expansion was a prodigious civilizing process, and at the same time the most destructive and ruinous because of the thousands of peoples, cultures and languages exterminated, the immense wealth it plundered and the flourishing civilizations it cut off and killed.

In the end, what was left was a vast recruitable labor force and an immense amount of lootable wealth (Ribeiro, Intr. XIII).

Gilberto Freyre, in Casa Grande e Senzala (1977), pointed out, however, that the Portuguese conquistador in Brazil lacked the combative ardor of the Spanish conquistador in Peru and Mexico. But it was, according to Lucena Giraldo (2003), more effective than the Spanish in occupying and controlling the Amazonian space.

Except in the case of the Jesuit missions in the Spanish Amazon, which guaranteed territorial coherence and a certain economic and organizational control of the indigenous establishments, for the benefit of the religious order.

The 16th century was such a harsh period that it can be catalogued as a genocide and ethnocide, especially in Brazil, where a process of involuntary extermination took place, due to epidemics transmitted by the whites, and to the violence unleashed by the conquerors against the indigenous people.

The bandeirantes of Brazil

Extreme violence was represented by the incursions of the bandeirantes, who were dedicated to exterminating and capturing indigenous people in order to reduce them to slavery.

The seventeenth century saw a decrease in violence and a period of settlement of the colonial order, in which the conquistador, the leading figure of the bloody times of the conquest and the armed occupation of small contingents of soldiers against masses of indigenous population, gave way to the missionary, the administrator and the naturalist.

The division of the Amazon and other lands of the new world.

These two centuries took place against a backdrop characterized by the division of the territory of the New World between two great maritime powers of the time: the Portuguese and the Spanish, and the temporary union of the crowns of these two kingdoms.

The partition of America occurred in the 15th century with three papal bulls.

1st papal bull

The first was the Bull Romanus Pontifex of 1454, in which Pope Nicholas V legalized European expansion.

2nd papal bull

The second was the Bull Inter Coetera of 1493, with which Pope Alexander VI extended to the kings of Spain the right to take possession of the New World.

3rd Papal Bull

The third was the Treaty of Tordesillas, in 1494, with which the kings of Portugal and Spain agreed on the division, with papal approval, of the extra-European world.

The Portuguese took the lands of the Atlantic Ocean, and the Spanish took the lands of the Pacific Ocean and the West Indies.

Two Kingdoms in One

The other event was the union of the crowns of Spain and Portugal.

In 1580 Portugal was annexed to the kingdom of Spain, under the house of Austria, during the period 1580-1640. In that period there was only one king, Philip (II, II and IV of Spain, who was I, II and III of Portugal).

Portugal regains its ground

The Portuguese restoration began in 1640 and was legally formalized in 1668, with the recognition of Portugal by Charles III.

During the period 1580-1640 the administration of Portugal and its overseas territories corresponded to the Portuguese themselves, under the supervision of Madrid, through the viceroy in Lisbon.

Then the Portuguese began to rebuild their territories and extend them.

Through the incursions of the bandeirantes, they penetrated the Amazon under Spanish rule, violating the Treaty of Tordesillas.

However, the effective occupation of the Portuguese over the Brazilian territory only took place at the end of the 17th century, and increased in the course of the 18th century.

The main protagonists

In those two bloody centuries, XVI and XVII, great actions of exploration and discovery were recorded, such as those carried out by Vicente Yánez Pinzón, Pedro Alvares Cabral, Francisco de Orellana and Pedro Texeira.

Yánez Pinzón: the Spanish navigator

The first European navigator to reach Brazil was the Spanish navigator Vicente Yánez Pinzón (1462-1514), who had been part of Columbus’ expedition in 1492 as captain of the caravel La Niña.

Yánez Pinzón left Palos de la Frontera, Spain, on November 19, 1499, with four caravels.

It crossed the Equator and headed for the coasts of South America. On January 26, 1500, he arrived in Brazil, unaware that it was an unknown territory.

He discovered the mouth of the Amazon River, the Gulf of Paria and the Gulf of Mexico, and returned to Spain.

Pedro Alvarez Cabral: Portuguese navigator

The Portuguese navigator Pedro Alvarez Cabral (1467-1520) arrived off the coast of Brazil in April 1500, three months after Yánez Pinzón, and took possession in the name of the Portuguese King Manuel I, applying the Treaty of Tordesillas.

Gonzalo Pizarro: the brother of the conquistador of Peru

Gonzalo Pizarro, younger brother of Francisco Pizarro, conqueror of Peru, was appointed governor of Quito in 1539.

Francisco ordered him in 1540 to undertake an expedition to conquer the eastern lands, to search for the cinnamon country, later joined by Captain Francisco de Orellana (1511-1546).

At a certain point in the journey, and faced with the dilemma of failure due to lack of maintenance for the troops, Gonzalo ordered Orellana to continue the journey in search of food and more resources.

Francisco de Orellana: the Spanish captain

Orellana and his people continued navigating the Coca River, and then the Napo, until they reached a very large river, the Amazon, on February 12, 1542.

After several months of sailing down the Amazon, Orellana and his people arrived at the mouth of the Amazon at the Atlantic Ocean on August 26, 1542.

After the trial accused of treason by Gonzalo Pizarro, Orellana proved his innocence, and returned to the Amazon River to travel in reverse, but died en route.

Pedro Texeira: the Portuguese cartographer

The Portuguese cartographer Pedro Texeira (1595-1662), during the time of the union of the crowns of Portugal and Spain, was sent to the Amazon in 1615 to consolidate the Iberian possessions.

In 1616, he was involved in the foundation of Presepio, the original nucleus of the city of Belém do Pará.

Between 1625 and 1636 he dedicated himself to fighting against Dutch and English incursions on the banks of the Xingu and Amazon rivers, while capturing Indians and trading them as slaves.

In 1637 he was given the order to navigate the Amazon River to establish the connection of the viceroyalty of Peru with the Atlantic Ocean, which had been partially traveled by Francisco de Orellana from Quito, almost a century earlier.

He sailed the entire Amazon, departing from Belém do Pará to Quito, returning to Belém in 1639, on the reverse voyage.

His expedition was part of the Hispanic model of colonization, establishing forts along the river to defend its navigation.

This trip is a pioneer in the colonization of the lower Amazon region, and was narrated by the Jesuit companion Cristobal de Acuña in the “New Discovery of the Amazon River”.

That trip served as the basis for the map of the Amazon River, which was later improved by others, including the Jesuit Samuel Fritz, who recorded it in Quito.

Walter Raleigh and piracy in the Amazon.

In the Orinoco region, it is important to remember the incursions of corsairs and pirates in Guyanese lands.

One of the most prominent and bloodthirsty adventurers was Walter Raleigh (1552-1618), who obsessively sought the riches of El Dorado in present-day Guyana and Trinidad.

In his conquests he succeeded in annexing part of Guyanese territory and Trinidad to England. Accused of repeatedly violating the agreements of the Treaty of Tordesillas, under protest of the Spanish monarchy, and of being complicit in internal conspiracies against King James I, successor of Queen Elizabeth I who supported him, he was imprisoned several times, until he was beheaded in 1618.

Raleigh’s and other corsairs such as John Hawkins and Francis Drake, attacking Spanish ships and possessions and trafficking in slaves in the New World, were always a headache for the Spanish administration in the 16th century.

Bibliography

Freyre, G. (1977). Casa Grande and Senzala. Introduction to the history of patriarchal society in Brazil. Caracas: Biblioteca Ayacucho.

Lucena-Giraldo, M. (2003). Confused empires, misguided travelers: Spanish and Portuguese on the Amazon frontier. Revista de Occidente, Madrid, Vol. 260, 24-35.

Ribeiro D., Araújo Moreira-Neto C. (1992). The Foundation of Brazil. Testimonials 1500-1700. Caracas: Biblioteca Ayacucho. Introduction by Darcy Ribeiro.

January 11, 2020

2 . Missionaries in the Amazon Rainforest (17th century)

January 13, 2020

3. The Utopia of the Earthly Paradise in the Amazon Rainforest

January 16, 2020

4. Great naturalist scientists in the Amazon Rainforest (18th to 19th centuries)

January 19, 2020

5 . The rubber barons between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century.

January 19, 2020

6 . Adventurers behind the Lost City of Z: the true story

January 20, 2020

7. The Amazon Rainforest today (XXI Century)

January 8, 2020

History of the Amazon Rainforest Explorers

This post is also available in:

![]() Español (Spanish)

Español (Spanish)