Nothing resisted him, until he decided to challenge the Amazon jungle.

Those blessed with success have dreams and utopias, but also failures, and sometimes very costly ones.

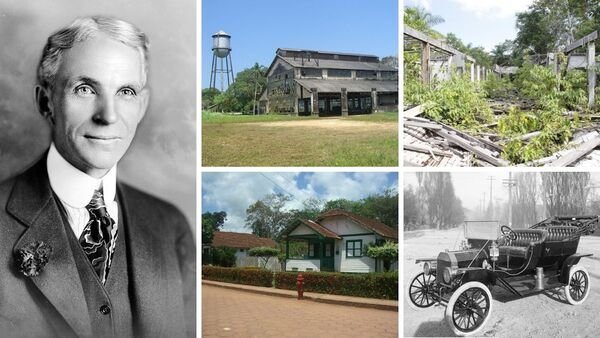

One of the great American industrial magnates of the 20th century was Henry Ford (1863-1947), son of a modest family of Irish farmers who came to the United States in 1847 and settled in the town of Dearborn in the state of Michigan.

It was a small rural town, where they installed a small agricultural and livestock farm without great pretensions, given their poverty.

Henry was born in that town and spent his childhood and part of his youth obsessed with his hobby of mechanics, so much so that he built a prototype agricultural tractor that was very rudimentary and in which no one was interested. He named it, presciently, Fordson, or Ford’s son.

Then, in 1896, at the age of 33, he managed to build his first four-wheeled car, powered by a two-cylinder, four-stroke, water-cooled, non-recoil engine. It was not a great novelty.

But he was already on the path of entrepreneurship, from which he would emerge triumphant in 1903, by creating his own company in the city of Detroit to manufacture automobiles: the Ford Motor Company (FMC).

Henry Ford’s Greatest Hits

What came next was a runaway success.

In 1904 he founded the FMC in Canada. That year his company produced 1,708 cars.

In 1908 he began mass-production of his Model T, cheaper than any other car, which catapulted him to fame and made him an American legend.

A few years later, in 1911, he created the FMC in England.

In 1922 he launched his candidacy for the White House. Nothing opposed his visionary mind.

The origin of Fordlandia

That same year Ford acquired 1,250,000 ha in the middle of the Amazon jungle, on the banks of the Tapajós River, a tributary of the Amazon River. There he created a city, Fordlandia, in the American style, as if it were located in the middle of Michigan, and not in the middle of the jungle.

In the 1920s, the cornerstone of American industrial development was the automobile industry. It was a time of stiff competition among car-producing companies, the number of which had shrunk from more than 100 at the turn of the 20th century to a sector run by three major conglomerates: General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler.

In those years, Ford was one of the largest and most successful entrepreneurs in the automotive industry in the world.

The year 1925 Ford produced 9,109 cars, an unprecedented production in the industry. In 1927 he looked for new challenges, suppressing the manufacture of his model T, which had given him so much fame.

The extraction of rubber as the motivating principle

Starting in 1928, Ford expanded to Europe: first to France, and then to Germany and Australia. And he decided to vertically integrate his conglomerate, expanding his control to the production of the raw material for the tires of his cars with his project of large latex plantations in the Brazilian Amazon.

That same year he began the construction of Fordlandia, his model city nestled in the Brazilian Amazon.

It was a personal whim. Ford controlled all the stages of its industry, except for the raw material it needed for its rubber tires (the modern tire had not yet been invented: Michelin would do it in 1948) and other automobile parts.

Historical context of the struggle for the exploitation of rubber

Wild rubber, Hevea brasiliensis, was abundant in the Amazon rainforest, especially in Brazil, Colombia, and Peru. Extractivist entrepreneurs, known as the rubber barons, harvested rubber from the forest, and also exploited indigenous labor, subjecting the indigenous peoples to a regime of slavery and police terror.

The prosperity derived from the extraction of Amazonian rubber lasted from 1879 to 1912.

During that period the British had managed to steal seeds of the rubber plant from the Amazon jungle, an action of biopiracy, not yet sufficiently sanctioned by universal legislation, using the intermediary of the English botanist and naturalist Henry Wickman.

They stole the seeds and genetically improved them to increase their resistance to disease and improve their productivity. They then planted them in the British colonies of Asia, using the plantation system of cultivation, a method different from the wild production of the species in the Amazon jungle (where there was a great dispersion between one rubber tree and another, a lack of roads, and long distances to export ports).

In the rubber plantations established in the Asian colonies, up to 80 trees per hectare were planted, compared with a maximum of 3 trees per hectare in the Amazon jungle.

These new producing regions, especially British Malaysia, flooded the world market with rubber at lower prices than that of the Amazon. In this way they monopolized the rubber market which, consequently, led to economic ruin in the producing areas of the Amazon basin .

Reasons for the debacle

Two events contributed to the disaster. One was the invention of synthetic rubber, which began to replace natural rubber.

The other, more severe, was the big crash — the great American depression of 1929 — which spread throughout the industrialized world, reducing industrial production and foreign trade, and leaving great economic ruin in its wake.

By that time the cruel and greedy rubber barons and the outrages committed against the indigenous Amazonians had already been left behind. Now the workers were the poor peasants and unemployed mestizo workers who roamed the north of Brazil.

How were the indigenous people hired by Ford?

Francisco de Assis Costa (2019. A brief economy history of the Amazon: 1720-1970 / Cambrigde Scholar Publishing) traces a brief history of the conversion of the indigenous people of the Indian towns, under the control of the religious missions .

According to his study, once the Jesuits were expelled in 1755, the people did not return to live as indigenous people in their native communities in the jungle, but instead became peasants. They created family production and consumption units, within which the fundamental economic decisions were not oriented to the market, but to family self-consumption.

In Brazil, those peasants, whom Costa called “Amazon cholo peasants,” were the rubber workers in the 19th century, specifically in the Brazilian north during the first period between 1850 and 1880, and who bore the heavy burden of rubber harvesting in later years.

At the beginning of the 20th century, in 1910, fifty-two percent of the rubber production capacity in the entire state of Pará depended on these Amazonian peasants. And they continued to produce latex from 1930 for the industries of Sao Paulo, along with cocoa and chestnuts .

The landscape of the automotive industry was changing, and new alternatives were emerging. But the Fordlandia project was already underway.

In 1928, the Amazonian rubber supply satisfied less than 3% of the world demand for rubber. The world supply of rubber raw material was monopolized by the English, who imposed their conditions on the market, based on the production of their colonies.

During World War II the Japanese, who were part of the coalition of the Axis forces, invaded the British colonies in Asia and broke the British monopoly on rubber, which was equivalent to wresting it from the Allied forces.

A new reason to accelerate Fordlandia

If Fordlandia made sense before war broke out, when considering the breakup of the British rubber monopoly, and the opportunity to achieve a certain independence in terms of supplying such an important raw material for its factories, its development was now even more justified, because American automakers did not have access to rubber from Asia, which they needed to equip their vehicles.

East Asian rubber posed many access problems for the US auto industry. At the beginning, the production was controlled by a British and Dutch monopoly. And later, under the Japanese occupation, by the axis countries, during World War II.

Starting in 1928, the implementation of Ford’s project in the Amazon accelerated. The first Fordlandia buildings were built in the middle of the jungle, in a vast area located between the cities of Santarem and Belém de Pará, in the north of Brazil, in the state of Pará.

What was Fordlandia like?

Ford built prefabricated houses, a large hospital, schools, urban planning, wide well-marked streets, a church, large hangars for workshops, a large social club, a nine-hole golf course, extensive gardens, dance halls, and 50 km of roads around the city so that cars could circulate in the future.

The star was the modern 100-bed, free-care hospital designed by the great architect Albert Kohn.

Managers were brought in from Michigan, paid double wages, and instructed to ensure good working and living conditions for the workers.

They created a city planned down to the last detail, imitating daily life in an American factory: the hours were from 9 am to 5 pm.

Alcohol consumption was prohibited, hobbies were golf, gardening, and dancing (but only to country music); a vegetarian diet of oatmeal, peach and brown rice was imposed, and a health squad was created to kill stray dogs and remove puddles to prevent malaria.

Workforce

Everything there was neat, almost aseptic, and the will of the worker was reflected in the smallest details. A Fordlandia native, the son of a laborer, said his parents were forced to obey orders like dogs.

But the workers — the rubber tappers and latex collectors — were accustomed to avoiding the unbearable heat by working very early until the sun rose. Later in the afternoon, when the sun beat down in its fury, they did not respect the imposed schedules and broke the rules of behavior. On weekends they went on their boats to the nearby “Island of Innocence,” where bars and brothels abounded.

American managers and their families, accustomed to the comfortable life of the cities, also did not adapt to the harsh conditions of life in the jungle.

Cocoa plantations also did not prosper. One year after planting, they were infected with diseases, mainly fungi. It was proven once again, after so many failed attempts, that homogeneous plantations or crops did not do well in the Amazon, where one of the most diverse but fragile ecosystems on Earth existed.

Ford’s Great Amazon Failure

Ford’s experiment was a remarkable failure in all respects. Trying to reverse the failure, Ford acquired another piece of land 80 kilometers further down the river and created the city of Belterra, which began to produce very slowly, without giving the expected results.

Date: September 2, 2010

Source: User: (WT-shared) Amitevron at wts wikivoyage / CC BY-SA

In 1945, after 17 years of his experiment, part of which involved time spent planning “in the United States,” plus the difficult period of construction of the complex in the middle of the jungle, as well as the initial process of adaptation and imposition of norms of behavior to the employees, everything collapsed.

In 1945 Ford transferred the city and the land to the Brazilian government for administration, after an agreed symbolic payment of $250,000.

That year, 1945, following World War II, the British recovered the rubber plantations in their colonies, but they had been practically destroyed.

Second Amazonian rubber boom

Meanwhile, the eyes of US industrialists had once again turned to the Amazon in search of reliable suppliers for their raw materials.

But that is another story: the second Amazonian rubber boom, which this time was short-lived, between 1942 and 1945, and had a sad ending.

It was led by an agreement — the Washington agreement — between the Brazilian government of Getulio Vargas and the US government to reactivate the productive areas of rubber in the Amazon, going from 15,000 to 45,000 tons per year.

To achieve this, at least 100,000 men, unemployed workers, had to be recruited to send to the jungle.

This time, the burden was carried by thousands of urban and mestizo workers who were mobilized in the so-called “rubber battle,” receiving a bonus of 100 dollars to cover travel expenses and the provision of basic equipment.

Spurred on by the promise of change, they went into the jungle, not in the best of conditions and rather hastily. From the northeast alone, 54,000 workers relocated.

The “rubber soldiers” starred in an episode that combined elements of heroism with airs of tragedy, leaving many deaths on the road and in the jungle, and which brought with it the defeat of any hope to regain economic prosperity through the exploitation of rubber in the Brazilian Amazon.

Fordlandia Today

After these episodes of failed illusions, Fordlandia is now a dilapidated, abandoned ghost town, overrun with weeds, where barely 2,000 people survive with nowhere else to go.

Date: 28 January 2016

Now it is only visited by a few tourists, who are willing to travel to see the tomb of an American dream, the great failure of Henry Ford, who could do almost anything, until he was defeated by the imposing Amazon jungle.

Tourists travel from Santorem to visit Fordlandia, taking about six hours by speedboat, or twelve hours by boat on regular routes, to stay in small hotels with pretensions of luxury, located no less than 70 km from the once ostentatious City of Ford, Fordlandia, which its owner never visited, but on which he spent an immense fortune.

Dr. Rafael Cartay is a Venezuelan economist, historian, and writer best known for his extensive work in gastronomy, and has received the National Nutrition Award, Gourmand World Cookbook Award, Best Kitchen Dictionary, and The Great Gold Fork. He began his research on the Amazon in 2014 and lived in Iquitos during 2015, where he wrote The Peruvian Amazon Table (2016), the Dictionary of Food and Cuisine of the Amazon Basin (2020), and the online portal delAmazonas.com, of which he is co-founder and main writer. Books by Rafael Cartay can be found on Amazon.com

This post is also available in:

![]() Español (Spanish)

Español (Spanish)